Insulux Glass Blocks, child of modern science, has picture of machine making blocks, exports of block

|

[Newspaper] Publication: The Muncie Sunday Star Muncie, IN, United States |

||||||||||||

|

Insulux Glass Blocks, The Nation's Newest Building Material, Child of Modern Science

Top — Inslux [sic] Insulux starts life as a molten 'gob' of glass which drops from the furnace into the forming machine. Of predetermined size and weight, it falls into the mold where it is pressed into shape of a half block by a descending plunger. The glass is "cooled" to a temperature of 1,000 degrees F. by successive blasts of air blown from compressors. Below — As the conveyor belt brings Insulux glass blocks from the annealing lehr at the Owens-Illinois Company plant on Macedonia avenue, these two workers examine each one carefully, ready to toss it aside if they find even the most minute flaw. This is one of the precautions taken to insure the high quality of Insulux.

Indiana and Ohio Limestone, Sand From Ottawa, Ill., Michigan Soda Ash, and Borax From California Are Elements Combined In Manufacture of Product At Owens-Illinois. By Paul Kelso. Out at the Owens-Illinois Glass Company plant on Macedonia avenue, workers equipped with asbestos covered tongs labor all day long at removing glass half-blocks from the revolving tables of glass machines. With movements that have grown automatic, they lift the half-blocks from the machine and place them on a conveying belt. Back, forward, back, forward. their arms move in unending cycle. These are the men who, working in the shadow of huge glass furnaces, see Insulux glass blocks, the nation's newest building material, grow from molten "gobs" of glass, still aglow with fiery furnace heat to definite shape and being. Child of Modern Science. They are the first of the many men who handle the block before it assumes final shape, before it finally becomes part of some modern home, factory or office building, or else is used in a cocktail bar, a filling station or a hamburg stand. Isulux is a child of modern science. It is a building material with a college education, Chemists, physicists, optical engineers and the workers who sweat from the heat of giant glass furnaces all have a part in its manufacture. Sand from Ottawa, Ill., limestone from Indiana and Ohio, soda ash from Michigan and borax from California are the component elements of Insulux. These materials are mixed automatically in voluminous hoppers, fed by automatic machines in the maws of giant furnaces and fused together by temperatures which climb to about 2,600 degree Fahrenheit. From the "refiner" end of the glass furnace, a glowing globule of transparent molten glass, its size and weight determined automatically, to the fraction of an inch and ounce, drops into the mold of the glass machine. A metal plunger forced into the mass of molten glass changes it into embryo Insulux. Placed on Moving Conveyor. Insulux is pressed, not blown glass. The outer surface of the plunger carries the reverse design of the interior of the half-block; the mold gives the half-block its outside design. After the plunger has left its impress, the half-block looks like a thin, glass box, the top side missing. The cooling touch of the plunger and mold cause the half-block to harden sufficiently to retain its shape after the plunger draws back to strike the next "gob" of molten glass. Blasts of air further cool the glass. By the time the mold has revolved to its final station on the forming machine, the glass is sufficiently rigid to be removed. Its temperature now is about 1000 degree Fahrenheit.

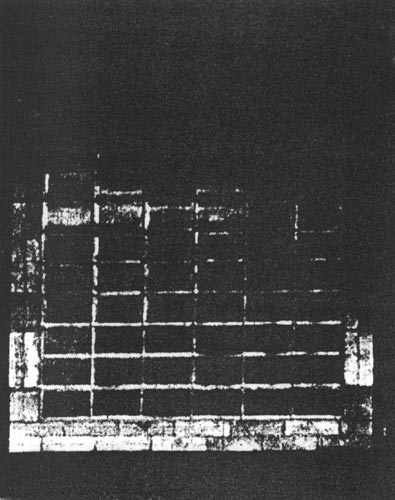

Panel After Test

This panel of Insulux glass blocks, tested for forty-five minutes last week by fire and then doused with a stream of cold water, remained intact, demonstrating that a wall of Insulux in a building will prevent a fire from spreading until firemen arrive, and then stand up under the impact of the torrent from fire hose. Waiting for the half-block, the worker removes it from the machine with his asbestos covered tongs and places it on the moving conveyor, which carries it to a molten metal bath. Another essentially important operation takes place at this junction. Another worker seizes the half-block and dips the open edges to the depth of about a quarter inch into the molten metal bath. The metal is considerably hotter than the glass. A chemical as well as a physical union between glass and metal occurs. Workers removed the half-blocks from the bath and quickly, out carefully, place two of them together, edges meeting in perfect union. The films of metal in the superimposed edges unite into & homogeneous mass and the halves are registered into place. The block formed from the two halves is placed under pressure while the metal cools. Acquires Insulating Qualities. Insulux begins to take on a familiar appearance once this union is completed. This stage in the manufacturing process also gives Insulux its insulating value. When the two half-blocks are clamped together, edges sealed by the molten metal which has united with the glass, the air in them, heated to a temperature of more than 1000 degrees, is abnormally expanded. When this air cools, a partial vacuum is created, and the block acquires its insulating properties against heat and cold. The super-heated air at this step also means Insulux will be free from condensation of moisture on the interior and that the block will never burst from interior pressure exerted by heat-expanded air. While they have the appearance of Insulux when removed from the joining press, the blocks are still unfinished glass, in need of "tempering." Consequently, they are conveyed to an automatic annealing lehr. For a period of several hours they move through a high temperature "soaking' zone. Then they move through zones of carefully controlled and gradually reduced heat. Finally they leave the lehr at normal temperature, perfectly annealed glass blocks. Inspectors waiting at the end of the conveyor belt bringing the annealed blocks from the lehr, examining them carefully, alert for even the most minute flaws. Blocks which do not meet their rigid specifications are tossed aside. Used In Foreign Countries. Samplings taken from the entire production at stipulated intervals as it moves from the lehr are subjected to gruelling tests to learn if the annealing process is functioning according to specifications and it the half blocks have been sealed perfectly. Next, in order for blocks passing these tests is the mortar-bearing surface-coat treatment. Surfaces of which bricklayers eventually will spread mortar are passed over a roller and roughly coated with a special preparation which looks like paint. Workers, with fast moving brushes fill spots not covered by the roller. This mortar-bearing surface-coat, a patented preparation which other companies have been unable to duplicate, is said to give Insulux the bonding strength demonstrated by exacting tests at Purdue University. The high shear and tensile strength of Insulux walls, which enables it to resist lateral wind pressure and other stresses, is acquired by this process. After the coating dries, the blocks once again are inspected and, if found perfect, are packed in cartons ready for shipment. Some may be used locally, while others will go into buildings in Alaska, Japan, South Africa, India, or British Columbia. Several orders have been shipped to these countries as well as many parts of Europe. |