[Trade Journal]

Publication: Electrical World and Engineer

New York, NY, United States

vol. 37, no. 1, p. 5-10, col. 1-2

The New Station of the New York Electric Vehicle

Transportation Company—I.

By R. A. FLIESS.

THE Twentieth Century—the much heralded horseless age--is here and its advent has been happily commemorated in the City of New York by the opening of the new station of the Electric Vehicle Transportation Company, at Forty-ninth Street and Eighth Avenue.

It is probable that the opening, at this particular time, of the largest automobile operating, charging, storage and repair station yet constructed emphasizes more strongly than would otherwise be the case the remarkable progress that has taken place in methods of transportation on land during the century just closed.

When one recalls the fact that at the beginning of the nineteenth century the only practical method of transportation available on land for commercial or pleasure purposes was the lumbering stage coach or a horse's back, the wonderful advance that has been made in this branch of human industry alone during the short period of the last one hundred years is truly marvelous and causes speculation on the possibilities of the twentieth century to carry one irresistible, far into a field which to our great grandfathers would have been the realm of wonders.

In this connection it may not be uninteresting to note that it is just one hundred years since the first attempt to construct an automobile in America was made. To some this may appear surprising, but it is on record that one Oliver Evans—a mechanic, born at Newport. Delaware, in 1755—in the year 1801, started to build a horseless vehicle to operate on common roads. Owing to the inability of the inventor to find a single one of his contemporaries who was willing to speculate to the necessary extent in the experiments which he desired to make or even to lend him the benefit of moral support, he gave up his attempt to build his automobile, but not before he has: made considerable progress towards the construction of a steam carriage designed to be driven by a non-condensing engine of his own design. This farsighted inventor predicted, however, at the time he gave up his attempt to construct a horseless carriage, that eventually vehicles would be propelled on common roads without the aid of horses, and that the time would come when people would travel in vehicles, moved by steam engines from one city to another, almost as fast as birds can fly. How fully this prediction, made just one hundred years ago, has been fulfilled, the thousands of miles of railroads and the rapidly increasing number of horseless vehicles now operating on our common roads bear eloquent testimony.

It was, however, only in the latter years of the last century that the great strides which have brought horseless vehicle locomotion on common roads to its present advanced stage of development, were made. Especially is this true in the case of electric vehicles, for it is only the developments that have taken place within the last twenty years that have made the electric automobile a commercial possibility. In fact, less than four years have elapsed since the first electric vehicle, built in this country to compete commercially with horse traction on common roads, was placed in operation. Since then the rapid strides that have been made in the development of this infant industry have been remarkable.

Perhaps, at the moment, no better idea of the magnitude of the development that has taken place in four short years can be obtained than is furnished by the brief history of the growth of the Electric Wagon and Carriage Company, from its small experimental beginning into the present Electric Vehicle Transportation Company, the new station of which has just been placed in operation.

HISTORICAL

On the evening of Jan. 20, 1897, the American Institute of Electrical Engineers devoted its 112th meeting to a topical discussion on "Electrically Driven Vehicles," during the course of which it was stated that the Electric Carriage & Wagon Company was equipping a station in New York City, for the purpose of running a dozen or more electric carriages for public and private service. It was said at the time that at first the service would be more or less selective, as the impossible or impracticable was not to he attempted. It was also said that, as this station was the first of its kind that had probably ever been equipped, a number of new problems was constantly arising, and that it would be some months before it would be known, with any degree of accuracy, what the probable results would be. Looking back from our present point of vantage it would seem as though even the most sanguine of the promoters of that pioneer company could hardly have foreseen the rapid expansion which it was destined to ensue in such a short space of time.

In its issues of August 14 and at, 1897, the Electrical World described the station of this company. The single room, 40 x 100 ft., which constituted its ground floor, was utilized as battery-charging room, vehicle-loading room, battery-switchboard room, washing room for vehicles and rental office, all in one.

The building, which was situated in Thirty-ninth Street, just west of Broadway, was a three-story one, and occupied a ground space of about 40x100 feet. Its total available floor space was 12,000 square feet, which, it may be interesting to note, is less than 10 per cent of that available in the Forty-ninth Street station. This pioneer station was equipped with 20 battery-charging stands, each of which would accommodate a battery of 44 cells. The new Forty-ninth Street station is equipped at present with charging racks enough to accommodate 640 batteries of 44 cells, and has been so planned and laid out that the battery-charging room can be extended in two directions, when desired, until it can be made to accommodate over woo batteries.

The rolling stock equipment of the Thirty-ninth Street station consisted of 12 hansom cabs and 1 brougham. The Forty-ninth Street station can accommodate 540 vehicles, with ample space left for their proper and easy manipulation, while over 700 vehicles could be crowded into the building, should the necessity arise. In fact, the Electric Vehicle Transportation Company expects to have the 300 vehicles, which make up its rolling stock equipment at present, in full operation in from thirty to sixty days provided they can get enough competent drivers in that time.

Not long after the Electric Carriage & Wagon Company began to operate its pioneer station, it became evident that its Thirty-ninth Street quarters would soon become inadequate. In fact, in less than nine months after its first service had been inaugurated the company, which in the interim had changed its name to the Electric Vehicle Company, moved its station to a building, situated between Fifty-second and Fifty-third Streets, the main entrance to which was on Broadway. This building occupied a ground space of about 75x185 ft., of which part was given up to offices. A space, about 36x130 ft., was partitioned off as a battery-charging room, the ceiling of which was 11 ft. high. This room could accommodate some 200 battery charging stands. The space above this room, some 4600 sq. ft., was used as a storage loft for vehicles. In the Forty-ninth Street station the battery-charging room occupies a floor space of 42x302 ft. and its ceiling is 20 ft. high. When enlarged to accommodate woo batteries, it will have a length of 474 ft. The storage room for vehicles in the new station is over 63,000 sq. ft.

As an indication of the growth of the business of the Electric Carriage & Wagon Company in its first months of business, the following data is interesting: During the month of March 1897, the company had 8 vehicles in actual operation. No record was kept in this month of the number of calls received, but the number of passengers carried was estimated at about 30o. Two more vehicles were placed in operation towards the end of the month. In April, 11 vehicles were kept in operation. The company received 280 calls for vehicles and carried 630 passengers, the a vehicles aggregating 1976 miles in that month. In May, so vehicles were kept in operation, 400 calls were received and 950 passengers were carried 2876 miles. In June, 11 vehicles were kept in operation, 632 calls were received, and 1580 passengers were carried 4603 miles. During the first year of its operation the vehicles of the company made a total of 45,833 miles, and as there were never more than to vehicles in actual operation on an average during the year each vehicle must have made about 4500 miles during that time.

The result of the first few months of operation of the Electric Carriage & Wagon Company's station, as has been shown, was very encouraging, and doubtless prompted its removal to the Fifty-third Street station.

A very good description of the old Fifty-third Street station was published in the Sept. 3, 1898, issue of the Electrical World. In that issue it was stated that "the construction of the most elaborately equipped charging station for electric vehicles in the United States, and probably in the world, had just been completed in New York City." Yet in a little over three years it has been found necessary to abandon it for the new Forty-ninth Street station, which is so much superior to it in every respect. In fact. even before this last move was made the increase in the business of the Electric Vehicle Transportation Company—successor to the Electric Vehicle Company—had made an addition to the Fifty-third Street station necessary. So some eighteen months ago a branch station was opened at Fiftieth Street and Eighth Avenue, in a building almost directly opposite the present Forty-ninth Street station.

·

·

THE BATTERY CHARGING ROOM.

This is a room 302 ft. long, 42 ft. wide and 20 ft. high, separated from the vehicle-loading room by a substantial partition of wood and glass.

The floor in this room is made up of a series of rectangularly-shaped spaces, formed by brick walls 8 ins. thick. These spaces are filled in with sand to a uniform level. A light layer of concrete is placed on the sand in which the cast-iron pedestal that supports the battery-charging racks are set. Above this comes a finished floor of acid-proof concrete in which the pedestals are firmly embedded. Ten channels or conduits, in which the wires from the battery switchboard are carried, extend the width of the room at varying intervals, as may be seen in Fig. 1. From each of these, five smaller channels branch at right angles. These channels, or conduits, are formed by the spaces left between the walls of the rectangularly-shaped floor spaces spoken of above. Fig. 1 shows the arrangements of these channels very clearly. It may be noticed that the channel marked main A carries all the wires equipped to charge the batteries placed in the racks which line each side of the branch channels numbered 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and which are on the eastern, or Eighth Avenue, side of main A.

The same arrangement is followed in the wiring of the other sections, each main channel feeding the branch channels, which are situated on its eastern side. The main and branch channels are lined with acid-proof concrete and the wires carried in them are kept in proper position and well separated by Alberine stone insulating slabs, placed vertically in the channels at convenient intervals. The wires pass through equally-spaced holes in the insulating slabs. By this arrangement, though in many of the main channels more than 70 separate wires are carried, each individual wire can be quickly and accurately traced from its switchboard panel to its battery rack.

A system of drainage for the battery floor is provided; each branch channel drains into its main channel and each main channel is connected, at its lowest point, with a pipe which runs the length of the battery room and finally discharges into the sewer.

The main and branch channels are covered with a wooden floor laid in small sections to facilitate its removal for inspecting the wires In this way a clear floor space is obtained, hardly a wire being visible to the casual observer.

| |||

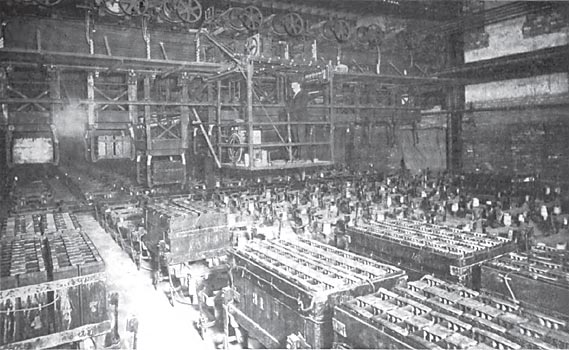

| Fig. 5. — Battery Room and Crane. |

Each battery rack, of which there are at present 640, consists of 4 cast-iron pedestals, 52 ins, high, firmly supported by the concrete floor. On each of these is placed a porcelain insulator, 7x4 1/2 ins., held in place by cement. Resting on these insulators are two cast-iron racks—each independently supported on two insulators. Two U bolts, as shown in Fig. 6, hold these racks in place. Fig. 6 also shows the details of the contact-making arm which automatically connects the batteries to the charging circuit when they are deposited on the rack. There are four of these arms connected to each rack. The I-shape cast-iron arms, pivoted as shown, have fastened to their outer end a straight piece of hard wood, 15 1/2 ins. long, covered with an acid-proof paint. At the free end of each wooden arm a contact block of hard wood is fastened. On the contact face of each block is placed a piece of brass, to which the charging wires, from the source of current supply, are connected. The operation of these arms is very simple. The weight of the descending battery depresses that portion of the arm which, when no battery is in place, protrudes slightly above the rack. Thus the brass-faced wooden blocks are forced against the contacts placed at the four corners of each battery box. The natural spring in the 15 ½-in. wooden arms assures a good contact. Each battery is connected in two groups of 22 cells, in such a way that by cross-connecting two diagonally opposite contact arms, the battery charges in series. The distance from the floor to the top surface of the charging rack is just one foot. The average height of a battery box is 1 ft. 6 in. Hence the top of each battery is on a convenient level for inspection of the cells, for filling them with acid and for reading their specific gravity, as seen in Fig. 5.

|

| Fig. 6. — Automatic Contact Arm on Battery Rack. |

Each battery rack is connected to its special panel on the battery switchboard by a No, 6 wire, as has been explained. In each branch channel is a 400,000-cm common return cable to which each charging rack is connected. This in turn is fastened to two 1,000,000-cm cable, two of which are placed in each main channel. These are connected, as has been noted, to the direct-current panels on the low-tension board in the rotary room.

In a succeeding article, the apparatus for handling the batteries will be described in detail.