[Trade Journal]

Publication: The Clay-Worker

Indianapolis, IN, United States

vol. 73, no. 2, p. 146-148, col. 1-2

AN EXEMPLARY PORCELAIN INSULATOR FACTORY.

RANKING AMONG the largest and most representative of the electrical porcelain plants of the country, the twelve-kiln insulator factory of the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company, at Derry, Pa., presents numerous interesting features. Located near the extensive gas fields of West Virginia, it uses gas exclusively for fuel, and is assured of an adequate supply at all times. Good transportation facilities are secured by its proximity to the Philadelphia-Pittsburgh main line division of the Pennsylvania railroad. The personnel of its organization comprises 300 people.

The plant occupies a plot measuring 600x500 feet, and is housed in a group of buildings comprising a two-story brick main structure 500 feet long by 150 feet wide, where the principal -manufacturing processes are conducted; a 160x213-foot building devoted to the shipping department; and several smaller structures containing the galvanizing machine and cooper shops.

| |||

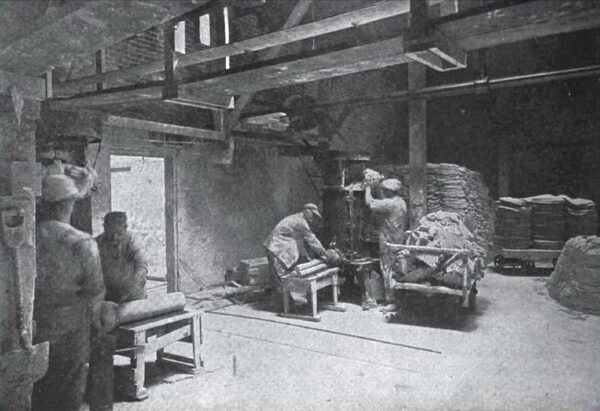

| Pug Mill in Clay Cellar, Westinghouse Insulator Plant |

The plant is thoroughly modern in its equipment and the processes follow the best approved methods of ceramic and industrial engineering. Electric motors are used throughout for driving the machinery, the power being purchased from the West Penn Power Company. Both the group and individual forms of drive are employed, with the individual method predominating. it is noteworthy that all of the barrels used for shipping purposes are made at the works.

The products consists exclusively of porcelain insulators, some of the varieties being the different types used in connection with high voltage power transmission lines; insulators designed for low-voltage apparatus; bushings and bus-bar supports. The sequence of manufacturing operations is systematized to a high degree of efficiency.

Mechanical Treatment of Mix.

The batches are usually weighed in lots of about one ton. Since they are sticky and hard to break up, the clays are weighed first and thrown into the “blunger” some time before the remaining ingredients are added. The blungers are great churns which beat and mix all the ingredients with water, so that after several hours of blunging, the mass is reduced to a thick, creamy consistency termed “slip." Having been blunged, the slip from several blungers is run together, mixed and allowed to run over a screen which is kept shaking or revolving by mechanical means. The screen catches the dirt and impurities and coarsely ground materials. The slip which runs through the screen goes into a cistern where it is kept in motion to prevent the heavier ingredients, the flint and feldspar from settling out.

From the cistern the slip is pumped up into filter presses. The water is strained out to a certain degree, leaving a cake containing a more or less definite water content. The time required to do the pumping, and the pressure to which it is necessary to pump, depend primarily upon the body mix. Commercially the pumping takes several hours for electrical porcelain.

After the pumping is completed, the cakes are transferred to a cellar and stored in a compact mass, which stands and ages for the purpose of allowing the water to thoroughly permeate all parts.

Having reached this stage. the mass is now intimately and thoroughly mixed by machines, to obtain the maximum de gree of plasticity and workableness as well as to eliminate as much as possible, the air in the clay. There are various sorts of machines for doing this, the commonest way being the “pug" mill. This is a tube or cylinder, horizontal or vertical, with a central shaft carrying knives. These knives, set at proper angles, cut and push the clay towards the end, where a relatively small hole allows the mixed clay to come out. As the clay comes from the pug mill, it is reworked by hand to a certain extent to eliminate possible flaws.

Forming the Ware.

In working the body into ware, the pugged material goes to the various benches, to be “jiggered" or pressed, or turned on a lathe. All these processes are really mechanical modifications of the ancient method of making clay ware by “throwing"; which consisted in placing a lump of clay at the center of a horizontal wheel which is kept spinning. The article is then pulled up and shaped by hand.

| |||

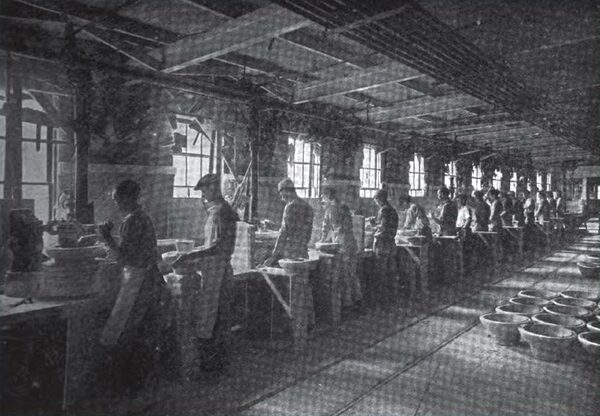

| Jigger Department of Exemplary Porcelain Insulator Factory |

To insure uniformity and gain speed, the jigger wheel came into use. Instead of a fiat horizontal wheel, a potshaped container is used, which holds s, plaster mold. This mold is shaped on the inside in the form of the outer surface of the piece to be manufactured. The inside of the piece is then shaped by a cutting edge or form called a "shoe,” which swings down in the arc of a circle or drops like a drill press.

A modification of this method is the jigger press, where the mold is held stationary, and the inside of the clay piece is shaped by a. core or plunger which does the spinning as it drops. The plunger must be kept heated to the right temperature or the clay will stick to it. In neither case is the operation quite as simple as it looks. The chunk of clay from which the ware is formed must be shaped by hand and worked somewhat, before dropping into the mold and, furthermore, it must be placed in rather carefully. The jiggered ware must be manipulated and smoothed by the workman while it is being shaped.

After being formed the mold and shaped ware are allowed to stand for several hours in order to stiffen.

After remaining in the molds a sufficient time to permit handling, the ware is removed and allowed to dry to what is termed the “leatherhard" condition, when it is delivered to the trimmer, who places it on a plaster shape which is the reverse of that in which it was formed. The plaster die fits the inside of the ware, leaving the outside exposed. The whole is set in a revolving container, and the trimmer smooths and finishes off the outer surface. The ware is then dried. In many cases, this procedure is reversed, i. e., the ware is dried to a condition termed "bone dry" and then trimmed. Both methods have their advantages and disadvantages.

Certain types of electrical porcelain, such as bushings and bus-bar supports, are quite difficult to handle by jiggering. In such cases, a cylinder of clay of correct size is squeezed from the pug mill and allowed to dry to a stage just right for turning. It is then placed on a mandrel and turned down like a piece of wood. It is easy to see that if the blanks are not properly pugged, dried and handled, they may turn out defective.

| |||

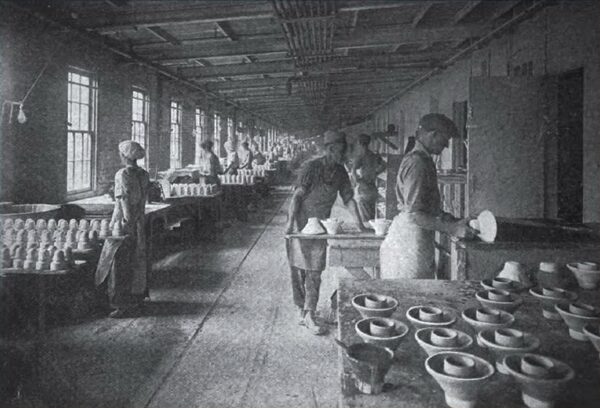

| Operation of Putting on Glaze Exemplary Porcelain Insulator Factory |

Glazing.

After being carefully dried, the ware is dipped in the glaze. This is a thin coat of glass made up of the same ingredients as the body, in different proportions and with materials added which will cause the mixture to melt to a glass long before the body itself. Generally a coloring oxide is added to produce the desired color.

Burning.

After glazing, the ware is ready for the kiln. Here the pieces are placed in “saggers" or refractory containers which hold the ware. The saggers are stacked one on top of another, until the kiln is filled. The firing generally covers a period of several days. The rate of temperature rise and the progress of heat treating or firing must be watched carefully. The means of doing this are several in number. The two methods of control in general use are pyrometers and pyrometric cones. The chief value of the pyrometer consists in the fact that it records the rate at which the temperature is changing, as well as the actual degree of temperature.

The pyrometric cone is a small pyramidal shaped affair made up of essentially the same ingredients as the porcelain body, but in such proportions that it fuses or bends over at fairly definite temperatures.

A whole series of commercial cones are made covering the range at which all pottery products are fired. The deformation of the cones at various temperatures, 36° F. (20° C.) apart is effected by varying the proportions of the ingredients slightly.

Cone plaques are placed in various parts of the kiln so that a uniform heat will be obtained. In addition to the cone whose deformation temperature is desired, a softer and a harder cone are set in the same plaque. During the firing the softer cone begins to deform first, thus giving warning that the kiln temperature is reaching the desired limit. The heat is then increased very carefully and the “full fire" cone deforms and the temperature is then slowly reduced.

After drawing from the kiln, the ware is ready for inspection. No ware with glaze defects or cracks in the body and no over-fired nor under-fired ware is tested or assembled. Before assembling, the separate parts are tested electrically, and after assembling the whole piece is tested. It is then ready for shipment.

A well-equipped laboratory is maintained at the plant for the experimental investigation of mixes. Because of the inherent peculiarities of particular clays which are due to their molecular structure or at least the conditions not fully understood by ceramic engineers, the search for the best porcelain mix involves a large amount of experimentation as well as theoretical computation.