[Trade Journal]

Publication: Transactions of the American Ceramic Society

Columbus, OH, United States

vol. 9, p. 187-194, col. 1

DATA ON PLASTER MOULDS

BY

GEORGE SIMCOE, Victor, N. Y.

In going over the subjects covered by papers in the transactions of the American Ceramic Society, nothing on the subject of Moulds can be found.

As this branch of the subject of pottery costs is a very important one, and one on which experience is general, it would seem that the subject should be started, and kept up till our records contain full data from every branch of the clay industry. The following little note is intended merely as a beginning, in the hope that it may bring in more valuable data from others.

The data here given is taken from the Locke Insulator Works, at Victor, N. Y.:

We have one mould maker, who turns out on an average of 80 to 100 dies per day. His wages are $2.40, and he uses from two to three barrels of plaster per day. The average consumption of plaster is about 700 barrels per year, which at $2.00 per barrel would amount to $1,400.00 for the plaster alone.

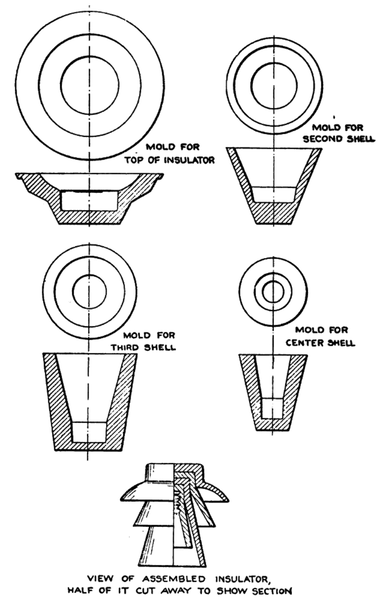

Our moulds vary in size from l"x3" to 30"x40", and in weight from 1 to 59 pounds. The wear and tear on them is very severe, because our ware must be even more solid than ordinary pottery, for cracks, however small, inside the ware, and not apparent on the outside, make splendid short-cuts for the electric current to break through. Our mould loss is increased very appreciably by "batting" clay into the moulds, and also the plunger process of forcing the clay into the mould causes much loss, due to rapid handling and great pressure. The following sketches show the cross section of one of the dies or moulds for making insulators:

|

| Moulds Used in Manufacturing High-Potential Insulators, at Victor, N. Y. |

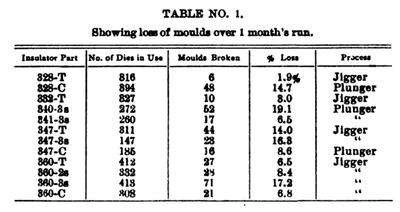

The difference in ratio of breakage of moulds in the plunger and jiggering process is well shown in the following table, No. 1:

|

| Table 1 |

From this table, we see a wide variation in loss which may be accounted for, first, by the size, i. e., large moulds naturally break oftener than small ones, and second, by the process of filling, whether by jigger or by plunger machine. In order to economize on the cup, it is often found practical to increase or decrease the cross section of the mould, so that it will be interchangeable. However, this is not always a good policy, for the table shows that mould number 360-3s suffers a high percent, of loss, through the making of a large mould too thin.

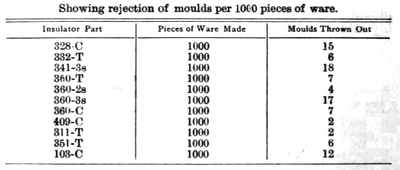

The next table shows the number of moulds thrown out in the manufacture of a unit quantity of 1000 pieces of ware.

|

| Table 2 |

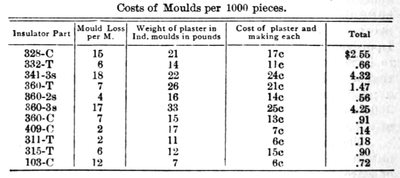

Table No. 2 as hardly comparable with Table No. 1, because the same number of moulds are not used at all times to produce 1000 pieces of ware. It has value, however, as it shows the location of leaks and their extent as represented by money, for from Table number 2, Table number 3 is deduced as follows:

|

| Table 3 |

To say what part of the cost of a piece of ware the mold represents is rather hard, but in the insulator business, I should say, from some careful calculation and estimation, that the moulds represent 1 percent, of the direct charge against the insulator. By direct charge, the actual cost, without any over-head proration such as salaries, office expense, advertising, insurance, etc., is meant.

In conclusion, I should like to ask representatives of the different branches of the craft to state through the Transactions what portion of their direct ware-making charge they assign to moulds.

DISCUSSION.

Professor Binns: Mr. Simcoe wrote me for information on this subject, but his questions only covered the matter of breakage in moulds, and in my experience I never found the matter of breakage of much importance. Moulds would wear out, the surface being destroyed, but it was very seldom that a mould broke. He has a different proposition, where they are used under pressure. I think the matter of the wearing of moulds is highly important, and we need more data in regard to the proportions of plaster, amount of water, etc. A mould-maker puts plaster into water until he thinks he has got enough, but so far as I know, we have no data whatever to tell us just what amount of plaster and water to use in order to get moulds of a certain density. In my judgment, we need information on that point more than we need data on the question of breakage.

Mr. Watts: I want to say in regard to wear of moulds, that we think that we have that matter pretty well in hand in our plants. We do not have serious difficulty in the wearing-out of moulds. We generally make about one hundred moulds for a ten-thousand order. We have a system whereby a man reports every night the number of moulds of each size that he loses during the day, and within the shortest possible time, those are replaced for him. We make up about ten percent, more moulds than we give to the jigger-man, and he gets a mould replaced for every one broken. I do not think that one hundred moulds for ten thousand pieces is at all a bad figure. Our loss is, more than anything else, in the number of moulds broken, which I think can be directly traced to the design or application of the mould. I have seen that in the whiteware and other lines of business, where I was satisfied if the shape of the mould had been corrected a little, the loss would have been very materially decreased. Moulds are often made which we think are thick enough to do the work, but after a few days' use, we find we have but a few left, and common sense teaches us that we must change the design in some way.

Mr. Gates: In making terra-cotta, the sharp particles of grog which must be used, cut down the life of a plaster mould very severely, and hammering the clay into the mold makes its life very short. Our great trouble has been in getting any kind of uniformity in our plaster; even when getting from the same factory, different grades of plaster are sent in every carload. We have to use those plasters which are cheapest for us, and of course are cut off from the use of some kinds; but even from the same factory the plaster varies widely in quality. Our moulds in the terracotta business are each made for one special job or order, and each is discarded when that one order is finished. Rarely do we find that we can use a mould on two different orders. Consequently the mould department is with us one of the heaviest expenses in getting out work.

Mr. Weelans: As to durability of moulds, it may be said that much is dependent upon how they are cared for. We find that the life of a mould differs widely with different operatives, hence it is difficult to determine just how long a particular mould of any kind may last.

The cost of moulds is an important factor in any business, and particularly in the sanitary line, and we have often endeavored to improve the lasting qualities of plaster by an admixture of other materials, but with no success. It is not the wearing out of the moulds, in the common acceptance of that term, however, but the breakage, that most concerns us. Our moulds are for the most part very heavy and difficult to handle, hence they receive more abuse than the smaller moulds used in manufacturing table ware. To determine the life of moulds is, therefore, a very indefinite proposition, and one not easily arrived at, for the above reasons.

Much variation in the life of moulds is occasioned: First, by the varying character of the plaster, even when from the same manufacturer; and second, the manner in which the same is mixed. Plaster, when mixed by a skilled mixer, has much longer life than when mixed by a less thoughtful and experienced operator. It is a matter of importance, therefore, that a proper percent, of water be used in mixing the plaster, and that the whole be properly mixed before using; otherwise, moulds are hard, soft, or lumpy, in turn.

The following mixture has always been found satisfactory: For ornamental work: One quart of water to 2 lbs. 2 oz. of finely ground plaster. For heavy work: 2 lbs. 6 oz. of plaster to one quart of water. The coarser the plaster, the more will be required to obtain the same given strength. Time should be taken to thoroughly mix same before using, and again, by exercising care in their use by not allowing them to become thoroughly saturated with water absorbed from the clay, but to dry them out at frequent intervals.

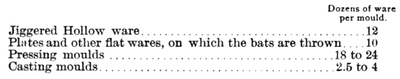

Mr. Hope: I have some figures here on the life of moulds, from which I will read a few:

|

The average jiggered moulds run about ten dozen to the mould, and as Mr. Weelans says, we must certainly specify the kind of moulds in discussing costs. I have no very accurate figures on casting moulds, but the mould cost in the casting process is very high.

I am working on some clay moulds to be used in the biscuit state, which I hope may be successful. I have made some very nice looking clay handle moulds but as yet have not given them a trial. If they can be used, it will be a great saving. Of course I understand that the idea of clay moulds is not new, as they have been used in England for a great many years. I have quite a lot of figures on the life of moulds, which I will be glad to give anyone who may be interested.

Mr. Gregory: The life of moulds may be extended by drying them properly. After a certain number of pieces are taken from the mould, put it in the drier, and the mould becomes stronger and will last much longer. Also, mixing two kinds of plaster makes a better mould. By experimenting, I found this gave better results.

Mr. Hope: I have tried the matter of drying slowly in the open air before using, and I find that it prolongs the life of a mould about ten percent.

Professor Binns: You mean the drying immediately after the mould has been cast? Mr. Hope: Yes. I have also experimented with adding materials to make the moulds harder, using dextrine in solution for this purpose, but it stops the pores and consequently retards absorption.

Professor Binns: There is one matter which I might mention in connection with the wear of moulds, and that is the influence of the body. Anyone who has made bone china may be aware of the fact that moulds used for this ware wear out much more rapidly than with a body containing no bone. I cannot give the reason.

Mr. Yates: I agree with Mr. Hope that if you take a mould and dry it out, after pressing a certain number of pieces, it will add greatly to the life of it.

Mr. Watts: We make a practice of putting all of the moulds in use in a fan ventilated drier or drier of some other type every Saturday, so that by Monday morning, the entire equipment of moulds is in good shape to go to work with. We have found this practice has made a great difference in the life of moulds.