[Newspaper]

Publication: The Muncie Star Press

Muncie, IN, United States

vol. 112, no. 222, p. 1 Section B, col. 2-4

A Navy Man

Armistice Day Memories Vivid for World War I Veteran

By RUBY SWICKARD

For the Muncie Star

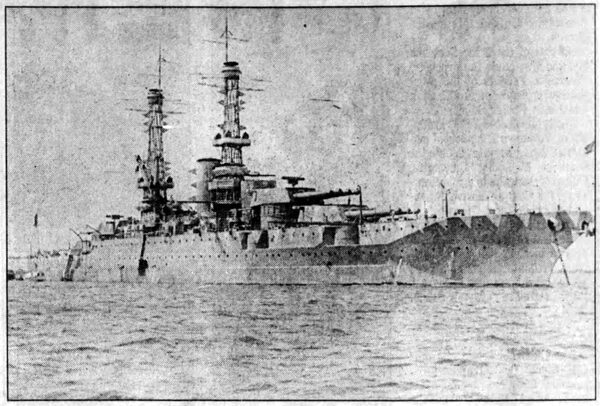

"On Armistice Day I was on the super dreadnaught, U.S.S. Mississippi. It was on patrol duty, a day and a half out from New York," said 92-year-old Martin (Dutch) Erlenbach of Muncie.

When the news of the end of World War I was announced, there wasn't much celebrating on shipboard, Erlenbach said. "But they had a big parade in New York like New Year's eve, I suppose," he said, "throwing confetti and everything else but I missed out on that."

Erlenbach's wife, Leila, remembers how Armistice Day, Nov. 11, 1918 was for her. "I worked in the office at the New York Store in Indianapolis. My family had just moved there from Muncie," Leila said. "Everybody was crazy. People in the store clerks everybody just walked out. There was so much traffic horns a-honking!"

There were no street cars running, and someone offered her a ride home. "Get on," the exuberant stranger said. So Leila rode home in style on the hood of a car!

Erlenbach's World War I experiences weave an interesting tale.

| |||

| MARTIN ERLENBACH's SHIP THE U.S.S. MISSISSIPPI |

"I joined the Navy," he said. "I wasn't drafted. I joined June 4, 1918 and spent 16 months in the Navy."

Erlenbach with four of his Muncie friends went to Indianapolis to enlist in the Naval Reserve. One man changed his mind, Erlenbach said. The thers, including Andy Sims and Bernard Cummings, passed the physical examinations and were sent to Great Lakes Naval Training Station near Chicago.

When the war ended, Erlenbach was transferred from duty on the battleship to the giant troopship Leviathan, a converted German luxury oceanliner that had been confiscated in port when the U.S. States declared war on Germany. The ship was 960 feet long, had 14 decks and a swimming pool, he said.

On one of Erlenbach's nine trips across the Atlantic transporting soldiers home, the Leviathan had a narrow escape. Sailing from France with 12,000 soldiers aboard, the ship came within 30 feet of a floating mine while off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. "If we'd hit it, that would have been all of it!" Erlenbach said. He has two newspaper clippings to corroborate his story.

On Sept. 29,1919, Erlenbach was released from active duty. but he retained his naval reserve status for several years.

"I didnt have to worry about a job... I was guaranteed a job [by Hemingray Glass Co.] when I got out," he said.

"A lot of World War I soldiers who weren't guaranteed their jobs... set up on Walnut Street to sell apples at a nickel apiece soldiers and sailors both with a basketful of apples." Erlenbach shook his head as he recalled the plight of some of the veterans.

| |||

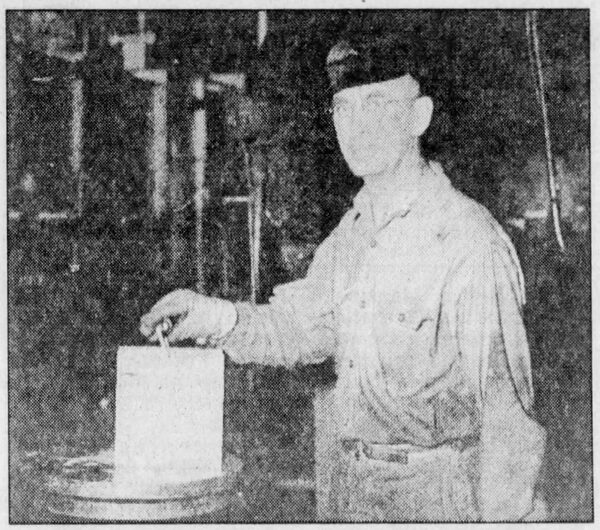

| ONE OF HEMINGRAY's SKILLED HAND GLASS WORKERS |

But Hemingray Glass Co., on South Macedonia Avenue, provided a job for Erlenbach who had begun work there in 1911 at the age of 14.

Erlenbach described the manufacturing process of glass insulators for electric and telephone lines.

"Glass is made of sand and soda and stuff like that," Erlenbach said. "And its melted with a very high temperature in big tanks tons of it at a time. A tank was as big as this house, and eight or nine machines worked on a tank.

"Hemingray made insulators, like that," he said, pointing to the blue-green insulators on the table in the enclosed porch. "We'd make about 4,500 little number 9s in eight hours.

"The gathering boy stood on a platform, and he'd stick the punty in and gather up the melted glass and drop it in the mold. Then the glass presser would cut it off and press the glass in the mold."

Erlenbach got up from his chair to retrieve a punty from his basement to demonstrate the action of the gathering boy. He thrust the metal pole with prongs into an imaginary tank of molten glass and twisted it round and round as he gathered it. "The gathering boy knew just about how much you needed for the size of the insulator," Erlenbach said.

"Its a pretty hot job standing in front of a furnace gathering a ball of glass, and the temperature of that around 3,500 to 4,000 degrees.

"Some days you'd sweat like hell," he said and laughed. "I say hell because in summer you'd burn up, and in winter freeze to death." The factory had no heat in winter other than from that used to melt the glass, he said.

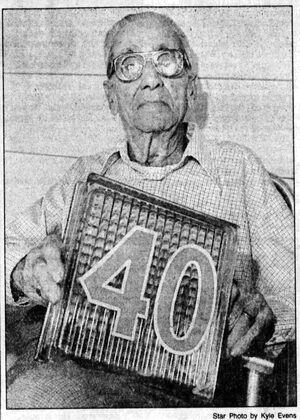

"Actually I am a hand glass worker," he said. And as far as he knows, he is the only hand glass worker still living of the 50 or 60 skilled glass craftsmen who ever worked for Hemingray.

"I started at a kid's job and learned the trade," he said. He began as "carrying-in boy" who placed the finished insulators on layers which conveyed the glass products through a tempering oven. The tempering process required 4 or 5 hours, Erlenbach said.

He also worked as a "taking-out boy" who removed insulators with tongs from the opened mold. Next he was a gathering boy and finally a glass-presser.

With advances in manufacturing technology in the 1920s, Erlenbach learned to operate automated machines. When Owens-Illinois purchased Hemingray in 1933, Erlenbach was employed in experimental work, helping to develop techniques and molds for successful production of glass blocks.

| |||

| MARTIN ERLENBACH WITH THE FRUITS OF HIS LABOR |

Erlenbach, retired in 1962 at 65, has been active in the Fraternal Order of Eagles, going through the chairs twice. He is a member of St. Lawrence Catholic Church and a life member of the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars.

When he was 75, he helped put on the roof of the new VFW building on Kilgore Avenue.

Erlenbach was born in Crown Point, Feb. 9, 1897. His parents, George and Katherine Erlenbach, moved to Muncie the following year. Erlenbach attended St. Lawrence School.

He said he was a boy of eight or nine when the downtown Ball Stores was built. He remembers the violence of the streetcar strike, a destructive fire at the Goddard warehouse at High and Seymour streets and the flood of 1913 when people climbed into rescue boats from their upstairs windows.

He also recalls a story about Ralph Hemingray, who with his brothers had moved their business from Covington, Ky. to Muncie in 1888. In the late '90s, Erlenbach said. Muncie had an ordinance against smoking cigarettes in public.

"Ralph Hemingray rolled his cigarettes and carried his own package of Bull Durham [tobacco]," Erlenbach said.

"You could smoke in your own home but in public you weren't allowed to."

Police were going to arrest Hemingray for making a cigarette and smoking it downtown. "And Ralph said. If you arrest me I'll move my factory out of Muncie.' They didnt arrest Ralph Hemingray!" Erlenbach said and chuckled.

As a young man, Erlenbach played factory league baseball with Clyde (Bucky) Crouse, a Hemingray employee who gained fame later with the Chicago White Sox.

On May 29, 1920, Leila Puckett and Martin Erlenbach were married. They had one child, Robert, named for Dutch's friend in the Navy.

"We had one boy," Leila said. "We lost him when he was 18, 3 weeks after he graduated. He never was sick and never had to have a doctor. He passed his physicals perfect. He was gone only 10 days. He got sick and died from cerebral meningitis in 1939."

"He was going to CCC [Civilian Conservation Corps] camp on his way to Washington from Fort Harrison," Martin said. "He died in Montana."

"He was a real good boy," his mother said.

Leila has worked as a police matron and in the Center Township trustee's office, the police department's juvenile division and county highway departments. She found an important role in life as an active Democrat in Muncie. She will be working at the polls this year in precinct 11. And Dutch is proud of the part she plays in local politics.

When Erlenbach was asked about his health, he said: "I'm fair. I ain't sick slowing up a little, maybe.

"I'm going to live 3 more years," he said. "When I retired in '62 I was 65. I said I hoped the good Lord would let me live 10 more years. When He gave me 10 years. I asked for 10 more. When He gives me 10 more, I'll ask for 10 more. I don't know how long He'll put up with it!

"I would like to hit 95. All my brothers and sisters are passed away," Erlenbach said.

"Martin was the oldest of seven children and he's the only one that's still living," Leila said. Then she added, "and the only one that got married!"