[Newspaper]

Publication: The Muncie Evening Press

Muncie, IN, United States

vol. 55, no. 49, p. 12, col. 1-9

"Home Grown" Product "Throws Light" on Building Industry

By BOB LOY

A home-grown Muncie product is one of the most important new building materials making possible the present-day functional architecture which combines siplicity with beauty.

Owens-Illinois Thinlite Curtain Wall, made here by O-I subsidiary, Kimble Glass, provide walls of glass which are both handsome and durable, allow the maximum of outside light to enter and at the same time are almost ridiculously easy to install.

When you look behind the fancy name, Curtain Wall is nothing more than glass-block construction, which is not new. Glass block was first introduced by Owens-Illinois at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933. Kimble Glass Co. has been making it here on a commercial basis since 1935. So what is so new about Curtain Wall?

The older masonry blocks are, it might be said, glass bricks. To build a wall you have to lay them one by one just the same as bricks.

With Thinlite Curtain Wall, however, the blocks are put together at the factory eight at a time in an aluminum framework and the builder merely has to fasten together the units. The new blocks are much lighter, also, being but two inches thick as against four inches for the masonry blocks.

Thinlite was about five years in the development and was introduced to the market just last year in June. Since that time it has gained considerable popularity in the building field, and has been used for office and factory buildings and schools.

|

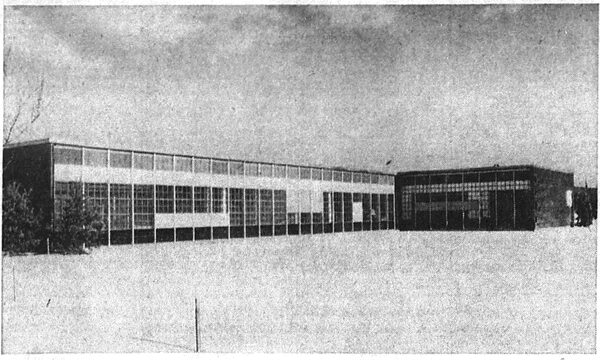

THIS IS HOW IT’S USED. The new plant of the Split Ball Bearing Co. at Lebanon, N.H., uses Curtain Wall on two sides of the L-shaped building. If this picture were in color you could see how the designer has used many colors for an attractive design. Thinlite basic tints, ceramic colors and clear glass panels have been used. The colors include blue, white, red, yellow and green.

Basic unit of Curtain Wall is a panel of eight blocks two feet high and either four or five feet long. These are bolted to vertical aluminum structural struts and can be built as high as the architect desires. Only tools required are a screw driver and a wrench.

A recent addition to the basic units is a block 12 inches high but only six inches wide. These can be interspersed among the regular blocks to provide more variety of design.

The panels are in three basic tints, rice paper white, sunlight yellow and cool green. These colors are induced in the glass by applying a "Silica Filter" finish to the inside surfaces of the hollow blocks.

In addition to the basic tints, there are ceramic, fired-on exteriors in eight striking colors. These include Chinese red, golden yellow, indigo, bronze, turquoise green, peacock blue, charcoal grey and ebony.

The panels can be made up any way the builder desires, all basic tints, all ceramic colors or any possible combination of the two. The combinations are limited only by the architect's imagination.

Clear panels to act as windows are also available which can be interspersed among the opaque, colored panels.

Thinlite glass blocks are described as “solar selecting” in that they let in the maximum of outside light while at the same time keeping out a considerable of the sun’s heat. Responsible for this property is the internal structure of the blocks which features little prisms impressed on the inside surfaces.

These prisms are so arranged that they will capture the maximum possible amount of light from the sun, no matter at what angle, and then will difuse it at the widest possible angle after it passes through to the inside of building.

This principle was perfected over a period of nearly 20 years by Dr. R. A. Boyd, the nation’s foremost authority on the control of daylight, at the University of Michigan. Owens-Illinois subsidized Boyd's work at the university which began in 1940.

As he went along, Dr. Boyd had to improvise and invent most of the equipment used in making his experiments. He built a wondrous artificial sun which, although it does not shine with the intensity of the real sun, can be made to simulate it as to position at any time of day, any season and at any place in the country. The artificial sun uses a 5,000-watt bulb that costs $40.

To test a glass block it is fixed in a special wall and the artificial sun is pointed at it in any position desired. Then on the opposite side, a photo-electric cell is mounted on a track which can be moved to any position in regard to the glass block The cell measures the mount of light coming through the block at all angles. Both sun and cell are operated by electric motors and can be moved to any position by push buttons at the will of the operator.

These instruments are invaluable in assisting engineers and architects in calculating heating, lighting and air conditioning requirements of new buildings. By rotating the sun through the various stages of the real sun, the total amount of light that will be received for an entire year can be calculated.

Another device developed by Dr. Boyd is a large pressed-aluminum ball, six feet in diameter, called an integrating sphere. The inside of this hollow ball is painted with a highly-reflecting paint. A glass block can be fixed in an opening in the wall of the ball then when a light from all sides of the ball. A photo-electric cell fixed in the ball measures the entire amount of light passing through the glass.

Until recently this equipment was at the University of Michigan. It is now here, at Kimble Glass, where J. A. Swaim, supervisor of molding, makes tests of the Thinlite blocks. It is the only equipment of its kind in the country and has been loaned to other companies for daylight experiments.

|

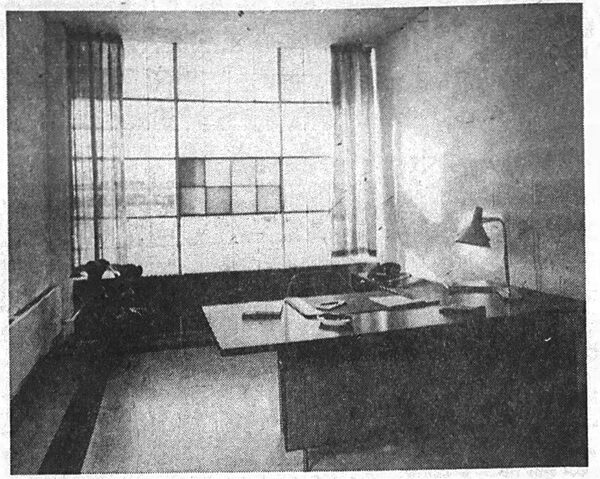

A PLEASANT PLACE IN WHICH TO WORK. One of the offices of the Split Ball Bearing Co. plant in Lebanon, N.H. uses Curtain Wall panels for a wall which provides a maximum of natural illumination and at the same time is handsome. While most of the area is made of clear glass panels, the top layer and the panel in the center are colored.

Some of the new buildings in which Curtain Wall is being used include a new National Container Corp. plant in Chicago which has a front wall 1,000 feet long constructed largely of the Muncie-made product; a school in Pittsburgh which has 23,000 square feet of Curtain Wall panels and the plant of the Split Ball Bearing Co. in Lebanon, N.H. The six-story Stephens Building now under construction in New Orleans will incorporate Curtain Wall panels in the top five floors.

Curtain Wall is proving to be quite popular in now school construction. Besides three schools in Pittsburgh, it has been used in school buildings in Gowrie, Ia., Farmington, Grand Rapids, Sparta and Stevensville, Mich., Willlamsville, N.Y., and Toledo, Ohio.

Complimenting the Curtain Wall are the Toplite Roof Panels for use in roofs. Like the Curtain Wall, the Toplite blocks are designed to pass through the maximum of outside light and at the same time reject the major part of the sun's heat.

The prism structure causes the blocks to transmit a high percentage of light from the low wintertime sun and reject the glare when the sun is high overhead in the summer. The laboratory at Kimble Glass has a device which illustrates this perfectly. A special cross section of the prism structure, several times actual size, has been set up with fixed lights that can show through it at three angles.

When either of the low angle lights shines on the prism, as the winter sun would do, the angle of the light is bent almost at right angles and passes straight through. But when the light directly over the prism is turned on the rays do not pass through but are deflected and pass back out. It is quite an interesting graphic illustration of the way in which the prisms operate.

Same as the Curtain Wall, the Toplite panels are prefabricated in the factory in a variety of sizes. The new fieldhouse soon to be built at Indiana University will have 262 four by six-foot Toplite panels or more than 6,200 square feet of glass in its roof. The designer of the IU field-house is designing another for Yale University which will also use Toplite panels.

With both Curtain Wall and Toplite panels, Owens-Illinois provides all the metal parts necessary for installation. Everything, of course, is insulated against the weather.

As glass is one of the most widely-used materials in modern architecture, Owens-Illinois Thinlite will become increasingly popular in the years ahead. And the only place in the world it is made is right here, in Muncie, in the plant of the Kimble Glass Company.