[Newspaper]

Publication: Poughkeepsie Sunday New Yorker

Poughkeepsie, NY, United States

vol. 67, no. 158, p. 9B, col. 6-8

|

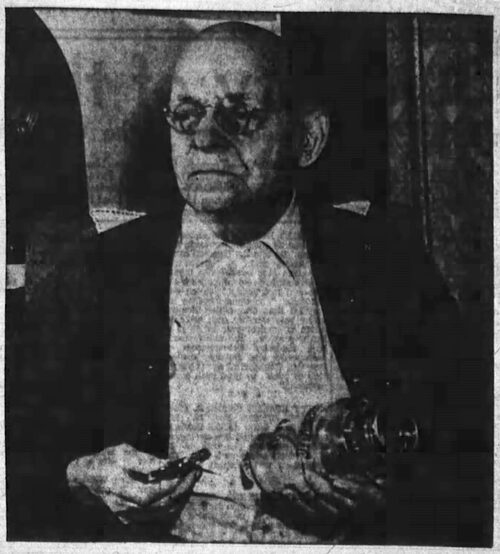

Poughkeepsie New Yorker Photo

George H. Foster shows a bottle that he blew half a century ago. He was then a blower at the old Poughkeepsie Glass works.

Good Pay, Good Hours, But —

Glass Blowing Was A Hard Trade

George Foster of Parker Avenue

Is One of Few Surviving Workers

Of Once Thriving Industry in City

Blowers at the Poughkeepsie Glass works were sitting pretty half a century ago. The pay was good, better than in the other trades. Many a professional men made less than a blower in the course of a year.

The hours were good, too, eight hours a day, and a two-month vacation in summer. But not everyone who aspired to be a blower succeeded. It was a hard trade to learn. All this was in the period of hand blowing before automatic machines were invented.

"Poughkeepsie Glass works was one of the biggest paying concerns that ever came to Poughkeepsie," George H. Foster of 46 Parker avenue said recently. "If you didn't make $6 or $7 a day — it was all piece work — they didn't want you.

"That was high pay then. They could get all the men they wanted for $1.25 a day. That was laborers. Plumbers and carpenters were getting about $2.

Mr. Foster believes that only three of the hand blowers are left now, Frank Hyer, Jacob Miller and himself. If there are others, they weren't union members. He knows there are now only three members of Local No. 62 of the Glass Bottle Blowers Association of the United States and Canada.

Mr. Foster helped organize that union in 1892, and is now its recording and financial secretary. But there are no meetings any more, he says. The three keep up their membership for the insurance and the contact with the trade.

* * *

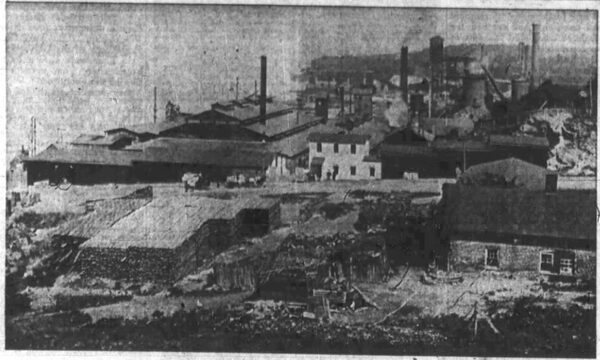

MR. FOSTER was 24, with 11 years of experience in paper mills, when he began work at the Poughkeepsie Glass works in 1890. The glass factory area was then at the foot of Hoffman street, and was one of Poughkeepsie's biggest and most successful industries. About 200 men were employed there, 60 of them blowers.

"They made everything down there from half-ounce pill bottles to carboys," Mr. Foster said. "A carboy? That's a great big bottle as big around as this" measuring a generous circumference with his arms. "They use them for oil of vitriol and such things. Paper mills use a lot of them because they have they have to have oil of vitriol in the manufacture of paper.

|

Mr. Foster as he looked when he was a blower at the old Poughkeepsie Glass works.

"Glass blowing is a hard trade to learn. A lot of them went in the glass business to learn it and couldn't. They had to give it up. You had to serve a five-year apprenticeship for half at what you made. You had to work for half of the list. If you were making beer or whiskey bottles at $1 a gross, all you got was 50 cents while you were an apprentice.

* * *

THAT was because an apprentice made more imperfect bottles. Of course you got paid only for the good ones. The bad ones were mashed up and put back in the furnace again. That cost the company money."

Three men worked together "in a shop," he said, two blowers and a gaffer or finisher. Each blower had a blowpipe, which, was simply a piece of iron had to be of a certain thickness so that it wouldn't burn off.

Glass is made from sea sand, soda ash and lime, he said. At the local glass works there was a 100-ton tank of molten glass that was kept hot and liquid with a gas fire that "was shooting right across it."

* * *

A glass blower began to make a bottle by heating the end of his blowpipe with its "milan," a bit of adhering glass, in the furnace that was under the molten glass. That's because hot glass won't stick to anything that isn't hot.

"The hot glass was in there like a pond," Mr. Foster said. "A blower had to put his pipe with the milan on the end in the hot glass and turn the pipe over and over to pick up the glass. By practice he could gauge the weight.

"That's why glass blowing is hard. Whatever class of glass you were making, you had to gather that weight. There's no way to measure it. Tht's where skill came in.

In some bottles, they'd allow you only half an ounce. If it was too heavy or too light they'd throw it away. That was true of of most all bottles. They'd allow you only a little variation."

* * *

THERE'S a good reason for that, he pointed out. Say a milk bottle is supposed to weigh 30 ounces. If it weighs 33 ounces, it won't hold a quart. If it weighs 28, it will hold more than a quart.

"After you had picked up the glass you had to work it on a plate," Mr. Foster said. "That's a slanted stone. You'd blow a little, and work it back and forth. Then you'd blow some more until it was a regular bag. Then you set it in the iron mould.

"After that you'd pull away and break off the end of the milan. You'd dip the tip and in water. If you didn't do that you'd have a lot of strings in your next bottle. Then you'd dive back and make another one."

* * *

THE third man in a shop, the gaffer, finished the bottle. Using a snap, a long-handled iron tool, he held the top of the neck in a "glory hole." This was a hole in an oil burner, with the fire forced through the hole from within. While this fire softened the glass, the gaffer worked the top edge smooth.

"The man who gaffered sat down," Mr. Foster said. "When you blow you have to stand. Usually the three men in a shop would take turns, with each one in the chair about half an hour gaffering. But some men couldn't blow. They had to gaffer all the time.

“Beer bottles we used to try to run about 60 in five minutes. That was in one shop with two blowers. Every shop had a scale. I've seen that scale teeter right on the weight all day long.”

* * *

WHEN Mr. Foster began work at the Poughkeepsie glass works there was no union there. He was one of the three or four glass blowers who started that union in Davy Crockett Hook and Ladder house. That was in 1892. The next year he became an officer. At one time he was union president.

Mr. Foster isn't an exempt fireman. He “got mad” at the Davy Crockett company before he had served the time that would have made him eligible for exemption. That was because he was fined after a fire on the Delafield St. bridge.

"Yes. I was at the fire," he said, but I didn't go back to roll call. I was soaked 50 cents for that. I said, "If they're going to soak me for out-of-town fires, I'm done."

* * *

MR. FOSTER wears a 50-year IOOF button with pride. He has been a member of the Poughkeepsie Lodge 21 for 53 years, but he has never held office. The brothers asked him to, but it just wasn't practical when he was a glass blower.

“We had an eight-hour day,” he said, “but we had to work nights one week and days the next. I didn't want to be an officer if I couldn't do it right. A glass factory fire runs all the time. It costs just as much to keep the fires when nobody is there as when somebody is working.”

Glass blowing is hot work, he said. You get 100 tons of melted glass and you get heat. Everything is hot, the snaps, the pipes, the glory holes. You stripped right down for your work. Even so, you often got so hot that everything turned black. Because of the heat the blowers never worked in July or August.

* * *

MR. FOSTER was employed by the glass factory when it was destroyed by fire in April, 1897, and returned when they modernized plant was built. He remained as long as hand blowing was done, and during the short period when hand machines were used.

"They put in what were called Teeple-Johnson hand machines," he said. "All we made on them was milks. Only two men worked together then. One gathered and the other worked the machine. There was no blowing by mouth. It was all by compressed air.

"I stayed until the factory closed up. That must have been around 1909 or 1910. When automatic machines were invented, that settled their hash. I guess there's only one hand-blown shop in the country now. That's at Smithport, Pa. The rest use machines.

"See this bottle? It was made in Olean. A fellow sent it to me a few days ago. It was all made by machine. The machine gathered it, blew it, put it in the annealing oven and all. It's a pretty nice piece of work for a machine."