[Trade Journal]

Publication: American Machinist

New York, NY, United States

vol. 20, no. 43, p. 805-806, col. 1-3

[The following article by the foreman mold-maker of the General Electric Company’s Works, at Schenectady, N. Y., relates to what is practically a new art – one of many to which the construction of electrical machinery has given rise. Porcelain manufacture is, of course, an old art, but until the demands for switch blocks and other insulating devices arose, the articles made of it were comparatively simple. The insulating properties of porcelain, together with its mechanical properties, make it a valuable material for the electrician; but the articles required by him are often of decidedly complicated shape, and the art of mold making for their manufacture had to be developed. Their process of manufacture is, of course, largely the same as die-sinking, although cores, loose pieces, etc., give also a semblance to patterns and core boxes. The molds when made are of a high degree of interest to any mechanic, being about the finest work of the die-sinking class that we have ever seen; many of them being, in fact, absolute works of art. Of their nature in this respect, elevations and sections can of course give no adequate idea. So far as we are aware, this is the first article upon this subject that has appeared in print. – Ed.]

The rapid advance in the uses of electricity has produced a great and growing demand for various articles of manufacture, technically known as insulations. These are very numerous, all varying in size and shape, with a difference in weight from ¼ ounce to 12 pounds, and are made of several compounds, among which is porcelain.

The General Electric Company, at the works at Schenectady, N. Y., have special departments where such pieces, in immense quantities and of every variety, are made. The intent of this letter is to briefly describe one of their processes for making porcelain insulation.

|

| The Porcelain Piece. |

Such pieces are molded in steel dies, of molds, operated upon by the pressure of a vertical hand, screw or lever press. These dies conform in every particular to the required article, so that the molding may be complete in one operating. The making of these dies requires great ingenuity and skill, so that they will be of the required shape, and will at the same time give proper allowance for “shrinkage” in baking, which varies more or less, according to the shape or density of the piece. The shape of these dies must necessarily be the reverse from the finished product.

|

| The Mold. |

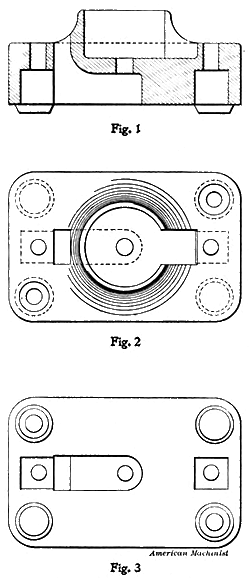

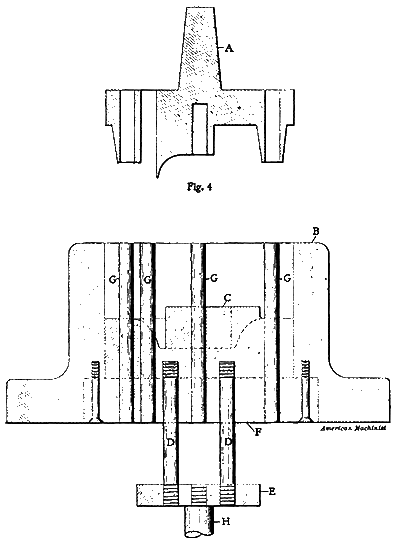

In the case of the piece to be described, two dies are used, one a male, the other a female; the former being the moving or pressure die; the latter the matrix, which is also movable. Fig. 1 is a section, Fig. 2 a plan and Fig. 3 a reversed plan of the under side of a porcelain piece of simple form. Fig. 4 is a section of the male die, conforming in shape to the under part of the piece, A being the tapered shank which fits the reciprocating spindle of the press. Fig. 5 is a section of the female dies and its several connections. B is a shoe attached to the fixed table of the press; C the female die, conforming in shape to the upper part of the piece. This die is fastened by two or more pins D D to a lifting plate or crosshead E, the pins passing through a guide or bottom plate F, bolted to the shoe B, to which are attached pins or rods G G G, which act as cores for making the necessary holes or perforations. This lifting plate E is fastened to the central pin H of a treadle or other suitable lifting device.

The method of working is as follows, vix.: The female die being in position, the proper amount of clay, determined by weight, is placed in the cavity of the shoe; the male die is the brought down in contact therewith, by the screw or lever, to the required pressure. This being done, the male die is released clear up from the shoe, and the treadle or lifting device is then operated, carrying the female die also out of the shoe and delivering the molded piece, so that it can be removed and the process of making another insulation repeated.

After pressing, the molded piece is dried, trimmed and take to the kiln for its first “firing.”

|

| "Saggars." |

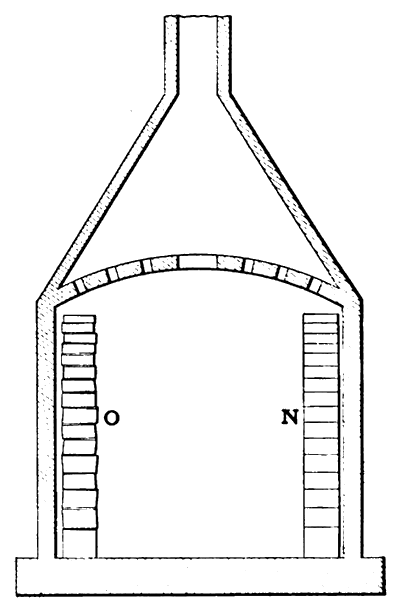

A brief description of a kiln and the method of firing will not be out of place. Kilns are commodious in size, of a circular section, with parallel walls to a certain height and then conical up to the stack. They are internally fired at the base at several equally spaced intervals. Some have down-draft others up-draft flues, but all are so arranged that the products of combustion will pass through the interstices of the several layers of porcelain. Anthracite coal is generally used as fuel.

|

| Porcelain Kiln. |

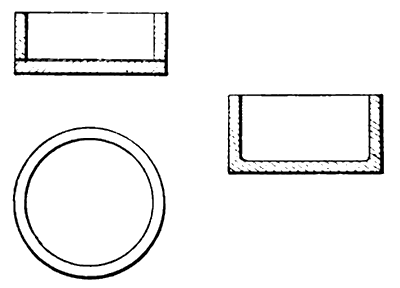

The filling, of charging, of a kiln requires considerable judgment and experience, so that it will hold all that it is possible, with good results, to get in, and so that there will be an even distribution of heat throughout; the largest pieces being set where the heat is the most intense. The several pieces of molded porcelain are packed in “saggars,” Fig. 6, made of fire-clay and of varying depths. These are filled as full as possible, care being taken that the pieces do not touch one another. These saggars are set in the kiln, one above another, with a binder or joint ring of raw clay between each, in tiers of about 13 feet high. Fig. 7 is a section of a kiln with two tiers of saggars in position, the fire grates and flues not being shown. The life of a saggar is about five firing. The ones commonly in use are spun, or otherwise made by hand, in two pieces, a base plate and a ring, which are jointed by luting and then bakes. This method causes great inequalities in height, etc., and in packing a kiln, the saggars being thus more or less not “true,” the tiers get out of line, thus endangering stability, taking up unnecessary room and causing leaks. This condition will be seen at O, Fig. 7.

Mr. August Webber, of Schenectady, has devised a new process for making saggars. He makes them in one piece, with good fillets in the corners. (See Fig. 8) His process obviates all previous difficulties, increases the life of a saggar 25 per cent., and gives 10 per cent. Increase in the yield of a kiln. His saggars being practically true, fit in perfect line. (See N, Fig. 7.)

By this process of “first firing.” The pieces of porcelain are vitrified throughout. Such is essential to an insulation, for if proper vitrifaction is not attained, there would be leakage of the electrical current, causing the piece to be valueless. After this process, the pieces are taken from the kiln, receive their coating for “glaze,” and are subjected to a second “firing.” In this operation they assume their well-known glossy appearance, lose their surface porosity, and are ready for use.

It may be finally added that they very best materials are required in this manufacture, as in some cases porcelain insulations are required to stand from 50,000 to 100,000 volts.

Schenectady, N. Y., Sept. 17, 1897.