[Newspaper]

Publication: The Muncie Evening Press

Muncie, IN, United States

p. 3

Hemingray Glass Co.:

2 men recall the history and old days at famous firm

By LEE GERHART

Evening Press feature writer

They worked 12 hours a day six days a week at the old Hemingray Glass Co. on South Macedonia, but when payday rolled around it brought a shower of gold upon all the 700 toilers.

Pay came on Wednesday and was doled out in $5 and $10 goldpieces, remembers Earl Quate, 2500 N. Rosewood, now 80 years old.

| |||

| Quate |

"On the night shift, I worked five 12-hour nights a week at $1.70 a night, or $8.50 a week,"Quate recalls. "On the day shift, I worked six 12-hour days at $1.70 a day, or $10.20 a week.

"I would get a $5 goldpiece and $3.50 in change for the night shift. For the day shift I would get a $10 goldpiece and 20 cents in change."

Young Earl, who commanded a wage of around 14 cents an hour, was the same number in age. What was a youngster of those minor years doing in a glass factory?

For one thing, there was a sick father at home and there were 10 other brothers and sisters in the family. And for another thing, the year was 1916 and to 1916 there were few laws against juvenile labor.

"Why they paid in gold I never found out," Quate remarks, and he never had a chance to save any of the gold eagles as pocket pieces that he could look at today, because he put every one of them in his mother's palm to trade for necessaries. She let him keep 20 cents of the change each week.

Earl's gold was very well earned. His job was as "pick-out boy" — using a fork to pick out insulators from the hot molds just after they had been pressed.

Young Earl never developed a deep fondness for Hemingray Co.'s gold because after a year and a half at the glassworks he moved over to Ball Corp., where he served out 50 years, mostly on the yard railroad, and earned a golden jubilee of employment before retiring in 1967.

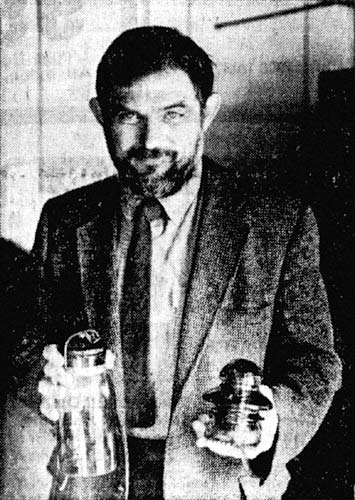

Muncie interior designer R. David Dale, 42, who has made an avocation of Hemingray Co. history and craftsmanship, never shared Earl Quate's advantage in working for Hemingray at 14 cents an hour. But Dale has volunteered his time in assembling a slide series on Hemingray for compensation even more modest than young Earl's: None at all.

The collection of Hemingray memorabilia that Dale can present on his slides is astonishing. There are company records, old copyright designs, pictures of old scenes in Cincinnati, Covington, Ky., and Muncie photographed from originals, and fragments that speak volumes, such as an invoice for a whole ton of white sand for only $2.50.

A month ago Dale went down to Covington, the suburb of Cincinnati that lies across the Ohio River in Kentucky, and with associate Richard Hakes combed over a recently bulldozed site at Second and Madison, which Hemingray occupied before moving to Muncie in 1889. Dale and Hakes were like Egyptologists searching for potsherds of the old pharoahs, and sure enough their indefatigability was rewarded by finding several precious shards of jars.

Just after Dale and Hakes left, the site became a parking lot for used cars.

Best remembered for their blue bulb-shaped insulators which used to festoon telegraph poles, Hemingray also manufactured fruit jars that today look both sturdy and elegant and have acquired value.

"Characteristics of Hemingray fruit jars were squarish shoulders and a tendency for aquamarine color," Dale mentions. "The earlier wax-sealed jars were bell-shaped while later jars were more upright."

Hemingray's jars join Ball's in getting good prices when they are free of cracks and chips and complete with correct lids and bands. Dale estimates that the Royal fruit jars are tops in the price line with a black glass fruit jar worth $1,000. Oldest and most precious jars were made in Covington, like the citron green jars of 1855 to 1870 that are worth $100 apiece.

But the made-in-Muncie line of Globe jars in colors of aqua, olive and Kelly green and amber have respectable worth, in Dale's estimate. He guesstimates $45 to $50 for the amber and olive green Globes and $18 for the most common aquas.

Hemingray's fundamental line was the insulators, which were required in great volume when the endless miles of telegraph wire followed the railroads across the continent.

"Insulators connect wires leading from one pole to another, and prevent the supporting points from becoming a ground, and the insulators must also avoid causing short circuits." In giving the definition, designer becomes electrical engineer for a moment.

"Hemingray tinted their insulator glass aqua-marine for purposes of corporate identity, and it just happened to be Ball blue," Dale smiles. He believes that iron pyrite gave Hemingray its peculiar blue-green color.

Dale credits Hemingray for introducing threaded insulators so that they could be screwed upon the pole, rather than just forced down upon a wooden peg. Hemingray also serrated the edges of their insulators to prevent moisture from accumulating and becoming an unwanted conductor.

Today only a ghost of the Hemingray glassworks stands on South Macedonia, where Owens-Illinois abandoned operations in June 1972, 39 years after acquiring the Hemingray firm in 1933.

| |||

| Hemingray historian R. David Dale |

That's the end of the story.

Start of the story, according to historian Dale, was in Johnstown, Pa., nearly a century and a half ago with two Johnstown natives, Ralph Gray and Robert Hemingray, who were to become partners.

Ralph Gray, Dale says, was first in the glass business in Cincinnati in 1847. Hemingray started out as a grocer and baker before moving to Pittsburgh, where he married Gray's sister and became a glass manufacturer. Dale asserts that Pittsburgh "was a glass-making capital before it became the Steel City."

In due time the brothers-in-law were together in Cincinnati, and decided upon a factory in Covington, which would supply a store at the other end of the bridge in Cincinnati.

Ralph Gray died in 1863, and the business name which had been Gray, Hemingray & Bros. became Hemingray Glass Co. Ralph Gray's name survived in Robert Hemingray's son, Ralph Gray Hemingray, who was to preside during much of the Muncie period.

Dale credits early Muncie industrialist James Boyce for being the prime mover in bringing the Hemingray Co. from Covington to Muncie. "With the discovery of natural gas here in 1887, Muncie had a lot to sell, and Boyce did the selling," according to Dale.

Although a business promotion group titled the "Manufacturers' Guarantee Fund" offered Hemingray a $10,000 bonus to come to Muncie, Dale feels that the money actually was Boyce's.

In return for $10,000, free land on South Macedonia and access to natural gas and water wells, the Hemingray Co. promised Muncie that would transfer all operations here and eventually employ 500 people.

When the Macedonia Avenue plant opened in 1889, a few months ahead of Ball Corp., the working force was 59 people, and Dale's detective work, in comparing Muncie and Covington city directories of the time has ascertained that at least 44 of these were glassworkers who moved from Covington. It wasn't until 1910 that the payroll numbered 500.

"Hemingray people were experimental and innovative," Dale lauds. "They were able to take an idea for a closure for a tin can and use it for a glass jar," and here he shows a slide of a jar that simulates a can.

Another slide shows Hemingray's ancestor of the automotive fuel pump. It was designed for the horseless carriages of 1900 and was a gravity-free device that led gasoline to the spark plugs. Many of Hemingray's experimental works were dumped, but Dale is silent on the dump locations to prevent excavating that could damage property.

To Dale, keen about the Hemingray firm's history and product line, the Hemingray Glass Co. was a pretty wonderful place because it turned out accessories that have become minor but precious works of art.

But in the memories of Earl Quate, who drudged there during endless hours of his boyhood for a golden pittance, there's not much romance.

"Our only breaks in the workday were once an hour when the waterboy came around with his bucket," Quate summons up one memory, "and we all drank from the same dipper."

He remembers Robert Gray Hemingray, too, who is a landmark figure in Dale's historical file on the glass company. "I remember Mr. Hemingray because he could wrap loose tobacco in a cigarette paper with one hand."

And that dexterity was appropriate because when he toiled there, Quate says he found everything at the Hemingray Glass Co. was manually operated.