[Trade Journal]

Publication: Journal of the Society of Telegraph Engineers

London, England

vol. 7, no. 21, p. 22-51, col. 1

The Sixty-third Ordinary General Meeting was held on Wednesday, February 13th, 1878, Professor ABEL, F.R.S., Past-President, in the Chair.

The CHAIRMAN: It is my painful duty to announce to the Members the death of an Honorary Member—Mr. Samuel Carter—formerly solicitor to the London and North Western Railway, and subsequently, for many years, solicitor to the Midland Railway. Mr. Samuel Carter was a valuable Member to us, and highly esteemed by all who knew him personally, but we have especial reason to regret his loss, and to bear respect for his memory, from the fact that it is to him entirely we owe the acquirement of that most valuable property—the Ronalds' Library. The credit is due to Mr. Samuel Carter, to whom that library was unreservedly bequeathed, that we have become possessors of that important collection, which is not only valuable in itself pecuniarily, but which really gives the Society additional importance, and I am sure you will all share in the feeling of regret at the death of Mr. Carter.

With reference to the announcement made at the last meeting that the office of Secretary to the Society would be filled up, I have to report to the Members, on behalf of the Council, that they have carefully considered the merits and claims of the various candidates who have applied for that appointment, and that their choice has fallen, after careful deliberation, upon Mr. F. H. Webb, who has been appointed Secretary to the Society, and will immediately take office in that capacity.

I will now call upon Mr. Preece to deliver his lecture upon the American Telegraph System.

Mr. W. H. PREECE: Mr. President and Gentlemen, It will be in the recollection of most of the Members present that in the spring of last year Mr. Henry Fischer, the Controller of the Central Telegraph Station, and myself, were appointed by the Government to proceed to America, and there to inspect and report upon the telegraphic system of that country. We left Liverpool in the Cunard steamship " Abyssinia " on the 4th of April, and after an extremely pleasant time on the ocean we arrived at New York on the 14th of April. Now, if there are any Members present who are wearied with work, or anxious for rest, or are desirous of peace and comfort—if they have good stomachs and good sea-legs, there is nothing on the face of the earth so calculated to put them right as to take a trip across the broad Atlantic. We arrived fit and well at New York, and we were received there, as I am sure every Member of this Society will always be received there, in a most cordial and hearty way. Everything we could possibly require was placed before us by the different Telegraph Companies; every officer of those Companies did his utmost to meet our wishes; and during our whole stay on that great Continent we never had occasion to look back upon anything with regret or to experience unpleasantness of any sort or kind. Now, Buckle wrote a book, in which he attempted to show that the characteristics of different nations were to a certain extent dependent upon the character of the climate of the country. We are all of us aware of the enormous energy—the go-aheadness of our good friends on the other side of the Atlantic. There is no great difficulty in attributing those characteristics to the beautiful air and bracing atmosphere of that portion of the world. As regards our two selves, we certainly, in the short time at our disposal, did an amount of work which, when we contemplate, makes us shudder. Our tour through America was not a great one when you look at the map. We arrived at New York and spent three or four weeks in that city in making ourselves thoroughly acquainted with the telegraph systems there. This was in itself no light task, because we had to unlearn a good deal that we had learnt in England and had to start upon an almost entirely new plan. We had to make ourselves acquainted not only with the engineering details but with the commercial details, the modes of transmission, the tariff, the sources of revenue, and with the rules and regulations of the Telegraph Companies there. This of course took a considerable amount of time. After spending sufficient time—about four weeks —in New York, we then travelled to Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington; thence we went up the Valley of the Potomac across the Alleghany Hills to the Valley of the Ohio and Cincinnati, then on to Indianapolis, and thence to Chicago. From Chicago we wandered through Canada to Niagara. There is not much in the telegraph way to be seen at Niagara, but we determined to see what was to be seen there of Nature's ways as thoroughly as we did at New York of telegraphic ways. From Niagara we went to Toronto, down the St. Lawrence to Montreal and Quebec, and thence across the White Mountains to Portsmouth, from thence to Boston, and thence by the Fall River to New York again.

Though our journey occupied several weeks, and though we travelled night and day over thousands of miles, still, when you compare our journey with the enormous continent itself, the space we covered was an extremely small one. Nevertheless we saw all we wanted to see of the telegraph system of the country, and learnt all we wished to know of that system. We moreover got thoroughly imbued with Yankee notions about hotel living, which to my mind far surpass European notions. If you want to know what hotel living is, go to the Fifth Avenue Hotel at New York, or the Palmer House at Chicago, or the Grand Union at Saratoga, where 1,800 guests are housed, who are attended to by 500 servants, and where therefore 2,300 mouths are fed every day without half the fuss you see in the dirty little hotels in some of our country towns. Then again, at these hotels, if you arrive hungry they can feed you, and naked they can clothe you. The entrance halls are surrounded by shops where you can get your hair cut or your face shaved. The barber is one of the institutions of the country. There is a druggist's if you are ill, or a tobacconist's if you are well. There is moreover a telegraph-office, a post-office, ticket-offices for the theatres and the railways, in fact it is a perfect cosmos of everything a traveller can possibly require. You can check your luggage to any place and never trouble your head about it until you arrive at your hotel at your journey's end. If you want to know what it is to travel in comfort, go to America. There you will find in regular use the luxurious Pullman cars--perfect drawing-rooms—in which you can sit before plate-glass windows and admire the passing scenery, or stroll about to prevent the effects of constraint. Passengers are always ready to chat, and there is an absence of that restraint extant in England. Thence you can pass into a sumptuous dining-room where you can obtain an elegant repast, and when you have finished that, and had your glass of wine, you go further and find another car fitted up as a luxurious smoking-room, with easy-chairs and round tables, and where you can have Parisian coffee brought to you. Then late in the evening when you go back to the drawing-room you find it converted into a bed-room, where you can turn in and sleep through the night, if so disposed—or rather if you are able so to do—for my own experience of three or four nights was, that a sleeping car was not a sleeping car for us. However it was a novelty and a sensation. The long distances and tedious journeys have necessitated these aids to comfort in America. They would be out of place in England. Nevertheless there are some conveniences in the American cars that would be a perfect Godsend at home.

There are many of us here who have had considerable experience in railway working in England. What would you think of a splendid trunk railway being worked without any signals, and where there are no names of stations conspicuous? Where no bell rings nor whistle sounds to start the train? Where no porters look after your luggage and everyone has to look after himself? Where you need not take a ticket but may pay en route? "The conductor" of the train is more like the captain of a ship. He is "hail-fellow well-met" with everyone. If he asks you a question you feel bound to answer him demurely. He wears no uniform, but is generally distinguished by a magnificent diamond pin.

The railways run on the level through towns without fencing or protection of any kind, and in one town (Elizabeth, New Jersey) the two principal railways cross each other on the level in the very centre of the principal street i I cannot dwell upon these social matters because you are naturally anxious to hear about what concerns us more. I could occupy you a considerable time with details of the pleasant friends we met, the pleasant hours we enjoyed, the sumptuous river steamers we boarded, the different scenes through which we passed, and the amusing episodes that occurred.

This great country is peculiar in its organization and many may not be acquainted with its constitution. There are thirty-eight partially independent states, nine organized territories, and two unorganized territories. Every state is practically an independent state ; each making its own laws, its own taxation, and is to all intents and purposes as much an independent country as France or Germany; while the representatives of these several states meet periodically at Washington to deal with imperial laws and questions, and mould together all these separate members into one well-cemented self-governed body. The Union is certainly a marvellous solution of an intricate political problem, and if the honest and the educated classes would only take part in the government of their country the constitution of the United States would leave little to be desired. As it is, corruption and dishonesty are so rampant that they have become a source of chaff rather than of shame. The openness with which the Americans pronounce their crying sin was one of the strangest features of our visit.

The constitution of public companies in America is very different from the constitution of public companies in England. As a rule, in England we have- a board of directors, presided over by a chairman and vice-chairman, having under them general managers, secretaries and executive officers, but there is a clear and broad line drawn between the administrative and the executive departments. The chairman and board of directors rarely, if ever—in fact never—interfere with the executive branch. They authorise all that is done, but for the chairman or board to take the absolute executive charge is a thing not known in England. In America the president of a company corresponds with our chairman, but he is not only chairman of the board of directors but also the general manager of the concern; he is in fact both the administrative and the executive head of the departments; and the vice-president in the same way takes under his charge distinct administrative business. The vice-presidents have various branches under their direct control, and are to all intents and purposes paid executive officers.

The telegraph system of the United States is a very large one. The absolute and correct statistics of the mileage of wires, the capital embarked, the number of stations, and various facts which we were anxious to get, we could not obtain, because such an enormous number of companies had been started, and had been in existence and had subsided, because different States and companies had different ways of keeping accounts, and because many companies found it politic to keep the information to themselves. However, we found that, altogether, in North America, there are about 300,000 miles of wires. Of these 300,000 miles the Western Union Company absorb by far the larger portion, having nearly 195,000, the Atlantic and Pacific have 36,000, the Telegraph Company of Montreal and Canada 20,000, the Dominion Telegraph Company of Canada 7,000, and other smaller companies and railways about 40,000; so that the actual length of wires in the United States and Canada is nearly 300,000 miles.

There are, altogether, 11,660 stations, and the total number of messages sent in the last twelve months was twenty-eight and a half millions. Invested in the present conduct of this large business there lies a capital of sixty million dollars, or about twelve millions sterling. How much capital has been sunk and lost is utterly unknown. At different periods of the history of the States there have been telegraph manias, just as there was a railway mania in this country in 1845, during which period, companies sprang up in every spot, and the amount of money raised, sunk, and lost, will perhaps never be known. The Western Union itself is a combination of no less than over two hundred distinct companies, that have at different times been brought into existence during these manias. In addition to these large companies there is quite a number of local companies. For instance, there is in New York a Gold and Stock Company, corresponding with the Exchange Telegraph Company in London. This does a large business in New York in supplying private wires, in communicating the variations in the price of gold and securities, and furnishing facilities that are most surprising to see. Then there is another company, the Law Telegraph Company, the offices of which are connected with the central station, by means of which lawyers can communicate with their clients, or with each other, with the greatest ease. There are domestic and district telegraph companies, which do an enormous amount of work. Then there are Railway Companies which have separate telegraph organisations of their own, and there is a large military telegraph system. In many parts of the States where the population is sparse, especially on frontier lines and where the Indians are troublesome, the Government have constructed for their own purposes lines of military telegraphs. There are about 2,500 miles of such military telegraphs in the United States, and these not only serve the purpose for which they were originally constructed, but, being carried round by the sea-coasts, do good service by conveying meteorological observations, which are not only a great boon to America itself but frequently prove a boon, though sometimes a nuisance, here. I say a nuisance, because when one is recovering from the effects of a fearful gale it is a terrible bore to be told that there is another to come five days afterwards. Nevertheless, these meteorological observations have, in a great many instances, proved correct, and we are beginning to pay some attention to those suggestions that come across the Atlantic.

Such is the telegraph system of the United States. In England we had on December 31st, 1877, 113,333 miles of wire and 5,328 offices belonging to the Post Office, and 21,977,084 messages were sent during the year. Probably the railway companies have 50,000 miles of wire, but statistics are wanting on this point.

I must, before going to the part which affects us Telegraph Engineers, tell you something about the commercial aspect of the question. The tariff of the United States is a very mixed affair. It is very anomalous. It is based probably upon a principle, but if so it is one of those things which is more honoured in the breach than in the observance. Now of course we all know that such a thing as a pure financial tariff scarcely exists—that is, a tariff that gives a fair return on the capital expended, or a tariff that gives a fair price for the work done. If any one were to ask you on what basis you should establish such a tariff you would say naturally it must be a tariff which is based upon a certain amount per word, and which shall vary with distance. The word is the unit of work done, and we all know that the cost of telegraphy increases with distance. But, owing to competition, to too great a desire to meet the assumed wants and wishes of the public, the simple tariff, varied by distance, has been spoilt, first by the addition of that "old man of the sea" in the way of free addresses ; secondly, by giving too many words as a minimum, and by the too extensive adoption of the uniform "penny postal" system. Now in the States the tariff is based upon ten words of text, the address of the receiver and the signature only of the sender being sent free. There is a practice there which does not exist here—which is, that a person need not pay for a message at the time. It is paid on delivery. The message is called a collect message. It is not much liked there by the companies, but is one of those bids for public favour which has crept in during the competition which existed between the companies. The tariff itself is divided into four distinct branches. First, there is the local tariff for messages in large towns or the area comprised between contiguous towns, viz., for any place within 25 miles, 25 cents, or one shilling, and for any place between 25 and 50 miles, 50 cents, or two shillings. The second tariff is very puzzling to understand thoroughly. It is called the " square rate." The whole of the North American continent is laid out in squares, each square having a side of 50 miles, and the tariff operates between any office in any one square and any office in any other square. For instance, the tariff between Chicago and New Orleans would be the tariff determined by the distance between the centre of the square in which Chicago is situated and the centre of the square in which New Orleans is situated. Again, taking St. Louis and Boston, the tariff would be determined by the distance between the centre of the square here [pointing on the map] and the centre of the square there [pointing], and so throughout the whole country. The tariff is divided in this way: For a distance of 100 miles, 40 cents; for 200 miles, 50 cents; for 400 miles, 75 cents; for 600 miles 1 dollar; for 800 miles 1.25 dollar; for 1,000 miles 1.5 dollar. That is in itself a very simple thing when you understand it, and if it were uniformly carried out; but, when you get to distances beyond 1,000 miles, then another tariff comes in, which is called the "State rate;" that is, between State and State over distances of 1,000 miles, where the tariff is based upon no principle, but is arbitrary, and varies from 2 to 3 dollars for 10 words. Besides that they have special rates. In some cases these square and State rates bear unequally, and, where competition has sprung up between places, special rates have been made. When we were there, there was a powerful and active competition between the Atlantic and Pacific Company and the Western Union Company, the result being the introduction of a uniform special rate of 25 cents, or 18., for 10 words, and in the New England States the maximum charge for 10 words was 30 cents. They have introduced the very excellent plan of charging for extra words beyond 10 words at per word. Our system in England is to make all extra charges rise by in-crements of 5 words. The American system is decidedly superior. The average tolls per message taken by the Western Union is 43.6 cents, or 1s. 9-3/4d.; in England it is 1s. 2d. Practically the cost of telegraphing in England is cheaper than in America; on the other hand we must remember the average distances in America are considerably greater than in England, but, neglecting mileage distances, a message of 20 words which would cost 1s. 10-1/2d. in America would cost only 1s. in England. There is, however, no fair comparison to be drawn' between the telegraph systems of England and America. For instance the length of our messages is different. The average of English messages is 30 words; the average of American messages is 23 words; while the average distances of messages in America, is several times that which messages travel in England. It is therefore difficult to draw comparisons between one and the other, and I do not intend to do it.

There is another system in vogue in America which we have not in England. They have a system of cheap deferred messages. A person can go to an office and send a message of ten words for half-rates on condition that it is sent at the convenience of the Telegraph Company and is not delivered till the next morning. Between towns where the post is slow, for instance, between New Orleans and New York, which is a two days' post, these deferred messages are very much patronised by the public. In fact, at New Orleans, of the total telegraph traffic 42 per cent. is done in deferred messages; but as we come nearer to New York, where the post is more rapid, and where letters posted at night are delivered the next morning, these deferred messages drop down to a very low figure. At Baltimore they are only 6 per cent. of the whole traffic. However, 13 per cent. of the whole traffic of the Western Union Company is made up of these deferred messages.

With regard to the Press, the arrangements in America are very similar to the press arrangements here. News is collected by press associations. It is carried by telegraph companies at lower rates, just the same as here. In America the rate for the carriage of these messages varies from one cent to ten cents per word. The lowest rate is one cent per word for every 500 miles. Additional copies are sent to the newspapers in the same town for half-rates, so that if a press association sent a message of 100 words to a newspaper in any particular place in the States it would cost at the minimum rate four shillings, and if an extra copy were wanted in the same town it would cost two shillings. In England the same service would be performed for one shilling and two pence respectively.

Now we all know that the rates in England are very low, indeed too low, and while the lowest rate in America, is one cent per word the uniform rate throughout the United Kingdom is a quarter of a cent per word. The result is that a considerably greater amount of press work is done in England than in America. In fact Mr. Fischer and I were greatly disappointed at the small amount of the press work done there. Now in England we often send on a busy night 500,000 words from the central station alone. There are also twenty-two special circuits worked in the newspaper offices, despatching about 10,000 words each. Thus on such nights our wires transmit about 700,000 words of news, and owing to so many stations working simultaneously on the same wires we deliver over two millions of words to the different newspapers. You may therefore readily understand we were not much struck with the amount of press work, about one-tenth, done in America.

There is one other class of business done there, viz., Government messages. Some years ago Congress passed a law by which every telegraph company subscribing to its terms was brought under the imperial law of the country on condition that they undertook to transmit Government messages on terms to be settled by the Postmaster-General. The result is they are now obliged to transmit messages for the Government at the rate of one cent per word for every 500 miles, and they do a pretty large business at that rate.

Free messages form a large portion of the business in America, and last year 712,000 messages were so sent. These free messages are often given for rent, and, as we used to do in England, they are given to railway companies for something received in return; now, unfortunately, we give it them for nothing received in return.

The same arrangements for repetition and insurance exist in America as used to exist here, and they carry on a large money transfer system which brings them in an annual revenue of 92,364 dollars. Money is sent for one per cent. commission; and 2,464,172 dollars were so sent last year by the Western Union Company. The largest sum sent is limited to 1,000 dollars, and that only to a few stations. The average amount transmitted is a small one.

Porterage is cheap, and messages are delivered within half a mile free.

I will now say two or three words about the staff. In America the telegraph service is quite a favourite service. The demand there is very great, and we always know that when the demand is upheld there is no falling off in the supply. It is looked upon with such favour and is so much thought of that it is quite an exception to find anybody who has not some knowledge of telegraphy. At Harvard College—our Oxford and Cambridge combined the undergraduates there have in their rooms their own telegraphs, which they put up themselves. They form themselves into companies, and it is one of the honours of the University to be associated with the leading companies of telegraphists. The people on the railways, station agents and superintendents, are also employed to a large extent on telegraph work, and nearly every station master has been at one time an operator. The pay is good. The average pay of the Western Union operators is 1921 per annum, while in England the average pay is only 801. Operators all over the country take great pride in their work. They look upon telegraphy as an art to be cultivated. You can hardly take up a professional newspaper without finding operators referred to by name, in terms more or less eulogistic of their abilities, such as " Mr. So-and-So is an excellent operator," "Mr. So-and-So has made very pretty copies," "Mr. So-and-So never breaks,' "Mr. So-and-So did so many messages in a given time."

Here is such an extract: " Greensburg, Pa. The late Jess Mills and Mr. Kettles, of Boston, sent and received 518 messages in nine hours. Messrs. W. G. Jones of Philadelphia, De Graw and McCarty of Washington, Phillips, Boileau, Taltavall, Baldwin, Moreland, Catlin, Bennet, and other New York men, have all made time nearer to fifty words per minute than to forty. We believe that Mr. E. C. Boileau, if not actually a faster, is a faster and better sender than any operator in this country; but if you know of anyone who has done better, and the case is well authenticated, we shall be glad to make it a matter of record." In fact great display is thus made of the abilities of the operators, who have thus established a kind of gazette of their doings in their art. The result is, these men take great pride in their profession, and they consequently acquire great skill in it. We have unquestionably excellent operators in England, some of them quite equal to the best Americans, but they are the exception not the rule. Taking their scientific attainments as a class, I do not think they are superior, or even equal, to the attainments of our best class of operators in England, for the simple reason that in England we have submarine cables and long underground lines involving the most abstruse laws of electricity, and we have more complicated and higher-classed apparatus. In America, you see every man operating with his right hand and timing with his left, and vice vend, and one was known to have sent a message with one hand while he received another message at the same time with the other. We are much inclined to discredit alleged displays of skill, because we are not able to do the same ourselves. We laugh sometimes at things we do not understand, and, if we are shown a complicated piece of apparatus which we cannot follow, we smile at it as an amusing and unnecessary thing. So it is with these displays of skill on the other side. I was myself as sceptical as anyone could be on these reported matters, but having seen some of that kind of thing done I came back quite a converted individual. One great incentive to progress is, that in America ability always secures its own reward. It is a saying that a French soldier always carries a marshal's baton in his knapsack, and so it can be said of an operator in the United States—he can rise up to any position in the telegraph system of that country, and it is a remarkable thing that amongst all the men I met on the other side connected with telegraphy there was not one who had not been an operator and who was not proud of acknowledging that he had been one. There are male and female operators. Females are not employed in telegraphy in America to quite so large an extent as in England, but still they are engaged to a very considerable extent. Their skill was as marked as that of the male operators, and they displayed an excellent knowledge of the technical branch of their business. Special engineering assistants are not known in the United States. No special means are taken to train up operators in technical and scientific attainments. " Self-help " is the motto of their education. But telegraphic periodical literature flourishes. Manuals and text-books abound. Electrical Societies for the mutual interchange of ideas and the imparting of knowledge are springing up, and the spirit of the age appears to be there—as it is here—progress.

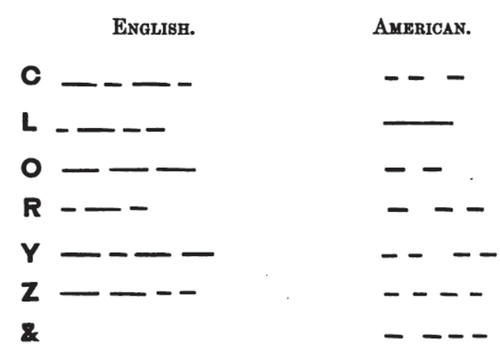

There is one curious departure from our practice, and that is in their alphabet. It differs considerably from ours. I have not given here all the letters in which they differ from us, but I show some particular letters. They have what are called space letters.

|

Take, for instance, " C." It is made up of two dots, space, and one dot, the space being equivalent to two dots. " L " again, dash—

equivalent to six dots. "0" is made of two dots, separated by a space. "R" is made up of one dot, space, and two dots. "Y," space and two dots. This is the alphabet first formed by Morse, but there is no question, and they admit it freely, although they believe the space letter system is quicker than ours, that it is nevertheless the cause of an enormous number of errors; and there are errors, or "bulls," as they are called, there, as there are errors here. I think, however, that their errors are principally due to these space letters, and some of them are strikingly curious. I will instance one to show you:—A lady received this message—"Mr. Sage has caved in, and is satisfied," whereas the proper message was—" Message received, and is satisfactory." Did time permit I could give heaps of such amusing "bulls."

Now, I come to the department more immediately affecting us—that is, the engineering details of the American system, and in: this department immense variation of practice has stepped in, due principally to the difference of climate, to the great distances which separate the different places, and also to the different and more difficult means of locomotion. The leading features of American telegraphy are extreme simplicity, great uniformity in the character of their stores, and in their mode of carrying out their works.

Now, with regard to construction. The same questions arose there as have arisen here, as between the relative merits of roads and railways, and, like the practice in England, the first telegraph companies made a start for the railways, and secured them as fast as they could. The result was that competing companies were forced to the roads, and we now find the country covered with telegraphs upon the railways and upon the roads. The cost of construction of telegraphs in America does not differ very much from the cost here. The average cost of a one-wire line varies from 100 to 160 dollars per mile, according to circumstances. That is not much more than we pay here. They have not much underground wire; in fact, the only piece of underground wire I saw is in the City of New York, and that is from the Central Station to the River Hudson, where two lines, 400 yards long, of 3-inch pipes, with 30 wires in each, are laid down. They go through their towns right through the main streets, and nothing is more striking to an Englishman's eyes than to go to New York and there see all the principal thoroughfares crowded with telegraph poles, disfiguring the streets right and left, and covering the sky-line with disfiguring clouds of wires. There are no less than ten distinct systems passing through the streets of New York, and in some streets no less than four distinct lines of poles crossing each other in every way. As the young gentlemen of America are as fond of kites as those in England, the result is that in Cincinnati I am afraid to tell you how many strings I saw fixed to one wire. It was an experience worth gaining to have learnt the possibility of such a state of things existing without causing trouble.

These pole-lines are some of them very fine indeed. They do not attach the wires to chimneys and roofs, but prefer carrying them through on poles. Going through New York, I saw two poles 96 filet high, with over 100 wires on them. In Philadelphia I saw poles 90 feet high ; in Chicago 75 feet high ; but all these lines were put up at tremendous cost, and I cannot help thinking that the opposition in America to underground wires is one of prejudice. I am certain that in New York and Philadelphia underground wires would be infinitely preferable, and more economical than those very massive poles. New York is on an island, and is separated from New Jersey by the Hudson River on the one side and from Brooklyn by the East River on the other side. These rivers are crossed by submarine cables of 7 wires made up to a weight of 8 tons per mile, and these are taken up for repairs and laid down again with great celerity. Owing to the nature of the bottom of the rivers, ships drag their anchors very much, and it is a frequent thing for the cable to be hooked five or six times a day. The result is that the Western Union Company is obliged to keep a tug always ready, with steam up, to help ships to clear their anchors and put all right again. But sometimes the cable gets damaged. I see here to-night some submarine engineers, and I have myself had some experience in repairing submarine cables, but if anybody had told me twelve months ago what I now tell you I should have listened and not believed. This will doubtless be the case with many of you, but in my case I had a witness and companion with me, who took the time with me. This steamer sailed up the river Hudson on one occasion whilst we were there, hooked the cable, and picked up a mile and a quarter of it in 20 fathoms water in 40 minutes, and then laid it down again on another route in 6 minutes. A submarine cable which in England would take a week to pick up and repair, and another week to lay down again, was picked up in 40 minutes and laid down in 6, the whole expedition not occupying over 4 hours. Now, with regard to their overland lines, they are as sound and good as anything we can produce in England. The poles are of an average height of 25 feet, and 6 inches in diameter at the top, principally of cedar, white or red, and they cost from 50 cents to 1 dollar a-piece. The price varies very much; they last under ordinary circumstances from 12 to 20 years. In many places they are of chestnut. The chestnut in America grows in a different way from what it does here. Our chestnut grows irregularly, but in America it is straight, and forms very excellent telegraph poles. In some parts they are of locust, a tree not unlike our laburnum; the flowers are however white, and it is a very pretty tree. In some places they use cyprus poles, and on the Pacific coast they use pine obtained from the primitive forests, a cheap timber, which lasts a long time. In England unprepared larch telegraph poles last 7 or 8 years, but in America their average life is about 15 years; the climate is so dry that it conduces to the preservation of timber by thoroughly seasoning it in situ. The result is that no preservative process is used, and I saw no instance of iron poles being used. The arms are of white pine, and of the uniform scantling of 4" x 5". Two wires require 3 feet arms; four wires 5 feet 6 arms; six wires 7 feet 6 arms. Where one wire is used they have oak and locust brackets of this kind (exhibiting), and sometimes they have the same insulators placed on the top of the pole by means of pins.

The wire used is sometimes galvanised and sometimes ungalva-nised. It was a source of surprise that in such an enlightened country they could put up wire ungalvanised, but those that had done it had good reason for doing so, at least they were able to adduce satisfactory reasons to themselves, the chief reason being economy, the chief culprits being the poorer companies, who were running the opposition. The great company—the Western Union—never thought of putting up ungalvanised wire. The question was raised while we were there as to the relative merits of the two, but the evidence from all parts was so much in favour of galvanised wire that I doubt very much whether any one in America would have the temerity to propose again the use of ungalvanised wire. The gauge of wire is No. 9 for short lines, No. 8 for medium lines; but No. 6 is used more generally, because practically their lengths are so great.

To America the credit is due of being first to introduce into iron wire the test for conductivity. That is rather a disgrace to us. We did not do it here. They have done so, and we followed their example; and I believe the example will be generally followed all over the world. The result has been much chagrin to wire manufacturers but much improvement to the working of telegraph lines.

Now, in America, they started what is called the ohm-mile. They specified that the quality of material of which the wire was composed should give an ohm-mile equal to 5,500 lbs.—that is, a mile of iron wire weighing 5,500 lbs. should give one ohm resistance. This would give fourteen ohms per mile to No. 8 wire. The result has been that they have succeeded in getting a wire which gives an ohm-mile weighing 4,884 lbs. The best we have hitherto got in England has been about 4,900 lbs., so that besides introducing that conductivity test they have succeeded in producing wire superior to what we obtain in England. There is a form of wire used in America called compound wire, consisting of a steel core surrounded with a tape of copper drawn through a tin bath. At least I do not know for certain, but I believe they used the tin bath. We were told that this wire had not succeeded, owing to the water getting in through the parting of the copper strip from the wire; the steel rusted, and the whole thing "burst up." Messrs. Wallace, of Ausonia, Connecticut, are producing a wire coated with copper by an electrolitic process. In England Messrs. Siemens are also improving that process, so that sooner or later we may succeed in getting a perfectly covered wire. No doubt it is a matter of great consideration to get a wire of the strength of No. 8, with the lightness of No. 16, and with the conductivity of No. 4.

The wires in America are pulled up rather loosely. Judging by the eye they are not pulled up with a greater strain than 200 pounds, in England our strain is about 300 pounds. We are obliged to do that, because our wires are carried closer to one another than they are in America, and we regulate our wires better. In America the arms are fixed 22 inches apart, and the arms being long the wires are separated by considerable distances, and in these days of fast speed telegraphy I think that that is a great advantage. We are very fond here of the Britannia joint, the joint introduced by Mr. Latimer Clark. We look upon that as the joint of all joints. The joint is stronger than the solid wire itself, and it gives no trouble. But they do not like it in America. Their joint is a mixture of the German twisted joint and somebody else's joint. It is a twisted joint, the centre of it being a long spiral, while each end is turned round three or four times. It is then dipped into a bath of solder, when it forms a good joint both electrically and mechanically, but not quite so good as the Britannia joint, for I have known cases of the wire breaking at the joint. The practice of soldering joints is now being generally introduced into America. We have always soldered our joints in England. Bad joints we never expect because we always solder them; but in America they have hitherto neglected this to a large extent, and in Canada in this year of grace 1878 they still do not solder their joints. The result of soldering has been this,—that, whereas a certain circuit with unsoldered joints gave a resistance of 23,500 ohms, as soon as the joints were soldered it gave a resistance of only 1417 ohms. I am happy to say that they are doing this in America now as fast as they can, and in course of time the whole system of the Western Union will be provided with soldered joints.

Now, in this large system of wires of 200,000 miles of the Western Union they only use one kind of insulator. That insulator is this annealed green glass insulator that is familiar to many of us (exhibiting). We used it largely many years ago, but we found that these insulators burst up from a cause that is absent in this insulator. We used to fix the iron bolts in our insulator with cement. At first we used sulphur, and the sulphur acting upon the iron formed a sulpburet of iron which expanded and burst the insulator. The result was, walking on the line you often heard them crack off like pistols. They have got over the difficulty in America by dispensing with the use of cement altogether, the insulator being screwed on to a wooden pin. As an insulator per 8e that is a very sorry affair. We could not work a line from London to Birmingham with such an insulator as that, but in America they have a bright pure atmosphere ; fogs are scarcely known ; those great aqueous clouds that envelope our country from end to end are never known, and my impression is that for several months out of the year they could almost work from New York to Chicago without insulators at all. There are some lines on the New England coast where the climate is very similar to that of England, but they have not got the aqueous clouds, as I term them, coming from the sea on to the land. The coast of New England skirts the ocean, and there are winds that blow from the sea to the land, but those winds come from a cold climate to a warm one. They pass over a polar current and come to a warm land. On the contrary, we have also winds coming from the sea to the land, but they come from a warm current to a cold one, and the result is they come charged to saturation with saline and other matters, and they coat all the insulators in their path with a conducting mass. The result is, that, however perfect the insulators, there are some lines in England where the insulation frequently breaks down. There are other insulators used in America. There is one called the Kenosha, made of baked wood steeped in some insulating compound. There is also another kind of insulator much used there on railway lines, and we have heard a good deal of it in England. It is one which has carried off a great many prizes at exhibitions, and I am pleased to say we have the presence here this evening of its inventor, Mr. David Brooks, from Philadelphia. It is used, over many thousand miles of wire in the United States, and as an insulator per se no doubt it is a very good one.

There are other classes of insulators adapted for parts where the wire runs through forests, where falling trees are a great source of trouble. In such places the wire is threaded through, as we originally did in England, and even now do on the South Eastern Railway. They do not bind the wire to the insulator with small wire, as we do, but they tie it by one turn of No. 8 or 9 wire. They do not use shackles, they are wiser in their generation. We have too largely used shackles. Staying and strutting, "bracing" they call it, is carried out only to a very small extent. Throughout my trip I did not see a dozen stays or struts. They strengthen their lines by freely using poles-40 to the mile is the usual number.

Again, the practice of earth-wires is not carried out to a large extent. The earth-wire is regarded as our safety-valve in England. It was originally introduced with the idea of protecting the poles from lightning; but it was found that an earth-wire run up a pole not only protected the pole from lightning, but carried away to earth extraneous currents that leak from one wire to another. The result was that where earth-wires were used we suffered in no way from weather contact, and we have since universally established the system of earth-wiring our poles. They have been introduced in America, but only to protect the poles from lightning. At some seasons their thunderstorms are very intense; in fact, the severity of our storms is nothing to theirs, and when a stroke of lightning does strike a line of poles they make a sorry figure of that line: 100 or 200 poles may at once be destroyed by a single flash; but wherever earth-wires have been erected this effect of lightning has entirely disappeared.

The leadings-in are extremely simple, economical, and effective. Their open-wire system enables them to effect this. Covered wire is very seldom used except inside the offices. The wires are invariably led to plate lightning-protectors, often placed in a cupola at the top of the offices.

It is rather a relief to find something to criticise unfavourably. Their battery system is indifferent. They use that extravagant form of battery—the Gravity—introduced in this country many years ago by Mr. Cromwell Varley, and speedily abandoned. Based on a fallacy, it leads "to wasteful and ridiculous excess." It used to quite irritate me to find this form of battery so very largely used, and on the closed circuit principle too. Its maintenance cost them on the average 58. 5d. per cell per annum. Our cells—the simple Daniell, with porous earthenware cells—cost less than 18. Having previously used the Groves' cell, this form to them has been a great improvement and a great economy, but there is no doubt that a lesson or two from England in this department will effect a still greater improvement and a greater economy. We recently had the pleasure of a visit from two of their ablest electricians, Messrs. Gerritt, Smith and Hamilton, and I have little doubt that these gentlemen will effect a reformation in this department. The telegraph lines in America are maintained in a very high degree of excellence. The criterion of the proper maintenance of a line is, first, its freedom from breaksdown; and secondly, the rapidity with which breaksdown, when they occur, are repaired. There is not much to say in favour of our country against theirs. Taking the mileage, we suffer from as many faults as they do, and they repair them in about the same time. But there is one practice in which they differ from ourselves, that is, that the responsibility of removing office faults is thrown upon the operating staff. Every manager of an office is responsible for the condition of the apparatus in his office. There are no such officers there as inspectors. There is nobody between the operator and the superintendent. The repairer or lineman is a man who receives a salary of about 2150, and is paid about as well as an inspector here. Indeed, he is to all intents and purposes an inspector.

The testing there is done entirely by the operators. There is a chief operator in each office, whose duty it is to be responsible for the condition of the batteries and apparatus, and to test the lines. One feature in every office is the total absence of galvanometers. If a fault comes on the clerk will test with his fingers. The climate is so dry, and the insulation so perfect, that they can, by receiving the return shock, with great accuracy localise the distance of a fault. I succeeded myself, by a little practice, in localising a fault within ten miles by the strength of the discharge received on my fingers. They now keep up their lines in a high state of conductivity, as I have previously remarked. The general system of working here is the closed circuit-system. This system has a great many advantages; in fact, the leading principle in telegraphy is that of simplicity and uniformity, and this is aided very much by the closed circuit system of working. It compels all the batteries to be concentrated at one spot. It simplifies the adjustment of the apparatus to the varying currents on the line; it enables many more stations to be worked on the same wire. I saw a circuit 457 miles long working well, with 57 stations upon it. It applies a constant test to a circuit, and it has many-points which commend themselves to our notice, and we shall to a certain extent avail ourselves more largely of the principle. On the other hand, open circuit working where the battery is lying idle at times is the principle adopted in this country. A circuit previously worked with 250 cells on the closed circuit system was more efficient with 75 cells on the open circuit system. In long circuits the open circuit is unquestionably the right system, and I have no doubt that by the introduction of the open circuit working they will be able not only considerably to reduce their battery power but to work better.

With regard to the forms of apparatus, telegraphy in this respect in America is reduced to simplicity and uniformity. The instrument found in every office, and that which is the basis of their system, is this simple little "sounder." I have brought one or two specimens of these sounders for your inspection to-night ; and wherever you go you find nothing but a simple key—here is one of these keys [exhibiting]—a relay and a sounder. These are all that are required to fit up an office in America; the battery, working on the closed system, is at the terminal station. Here we have telegraphy reduced to the greatest point of simplicity, and the cost of maintenance minimised to its lowest limit. By the use of the sounder for the transmission of messages you increase the capacity of the wires for the transmission of messages and secure greater accuracy in the despatch of business. Many of you are aware of my opinions as to the advantages of "sound" working, and if I have learnt nothing else from my trip I have learnt the immense advantage of that mode of working. The keys are simple. The relays, which are nonpolarized, equally so. The distinguishing features of their relays is their low resistance, (150 ohms,) and the smallness of their coils. They have thus by practice arrived at the same conclusion as we in England, that faster and better working is attained by reducing the size of the cores of relays and their resistance. Theory, from neglecting conditions, has been very far out in indicating the proper resistance of relays.

Working as they do to great distances, they have carried out "repeater" working to a large extent. Direct working is rarely carried on to a greater distance than 600 miles; beyond this, repeaters are used sometimes two and sometimes three for their longest distances. Between New York and New Orleans, for instance, 1,450 miles, there are repeaters at Washington and Augusta. There is scarcely an office of any size which has not several of these repeaters. Washington, Baltimore, Buffalo, and Boston have five or six repeaters each, which are used regularly and irregularly. When the weather becomes bad, and troubles arise, they fly to these repeaters. One of the most striking features of the repeater is this -- the introduction of two or three repeaters on the circuit from New York to the long distances to Chicago, New Orleans, St. Louis, &c., does not interfere with the rate of working, and the messages come off as quick as the clerk could read them. That, I may say, is contrary to our experience in Europe. The introduction of translators on long circuits worked by key has been to lower the rate of working, and the greater the distance the slower was the rate of working. Duplex working has met with great advance in America. It was, indeed, resuscitated there. It remained dormant for many years, and then, on its introduction by Stearns, who overcame the difficulties of working by the application of the condenser, it received a fillip which has forced its employment over the whole world. In America it is of course used to a very large extent. It was also used by the opposition company, the Atlantic and Pacific, but as they had not the right to use the patent for condensers they have been obliged to dispense with them. They used a system known as D'Infreville's, but which is the system introduced here by Mr. G. K. Winter. It is an extremely simple and rapid mode of duplex working. There is also another duplex system by Haskins which is in use by the North Western Telegraph Company. Duplex telegraphy led to diplex. By the former, two messages could be sent on the same wire in opposite directions; by the diplex your two messages can be sent in the same direction on the same wire; whilst by the quadruplex system you can send two messages in each direction at the same time ; and, not to weary you by other "plexes," every other style is called multiplex. I have seen all these systems worked. It would take a whole evening to attempt to describe the quadruplex working. It has been before the Society before. It may shortly be stated to depend upon these principles—that you have in the first place a duplex system worked with reversed currents; secondly, that you have the duplex system worked with increment and decrement of the current, and you have those two working together. The two things work side by side with perfect success. The quadruplex system has been established between London and Liverpool, and nothing could be more successful. Multiplex working is this—the system introduced, by Mr. Gray at Chicago was based upon the same idea as the patent taken out by Mr. Cromwell Varley in 1870. The principle of the two is identical. Between Chicago and Dubuque there is a circuit providing for seventeen intermediate stations. These work as ordinary Morse sounder circuits, and are now working as such; but between the two terminal stations there is on the same wire a telephonic circuit, or rather there is a circuit worked by the rapid vibrations of another battery, which, being simple vibrations, superpose themselves on the working currents. They are received at each end by telephonic apparatus, and Chicago can work to Dubuque without interfering with the messages at the other stations, which are worked by means of the ordinary sounder. This has been tried on other circuits, but when I was there it had not arrived at such a condition of perfection as would justify the recommendation of its being tried here. I have heard since that it has been found extremely practicable. While 225 messages were exchanged between the various stations on the circuit by means of the sounders, 300 messages were exchanged on the same wire between Chicago and Dubuque. I have no doubt one fine day we shall find some one coming over here with apparatus for us to try.

Type printers! The. type printer also originally sprang from America. Our friend Professor Hughes tried years ago to introduce type-printers into America, but did not find our friends there so ready to accept his apparatus. He came to England and established the Hughes' apparatus in Europe. In America this same apparatus which has since been perfected by Professor Hughes was worked, under the able guidance of Mr. Phelps, on the Western Union system, and he has converted it into another printer, which however in its main principle is the same as Professor Hughes's, though differing from. it in detail. He calls it an electromotor machine, because it is driven by an electro-magnetic machine, but in other respects it is the same in principle as the Hughes. It is not used to a large extent by the Western Union Company, but a modification of it is employed to a considerable extent for private wire working. There is another form of type printer by Mr. Gray, and one by Mr. Edison, which are used for the transmission of commercial news and prices, and for private wires by the local telegraph companies.

Messrs. Welsh and Anders, of Boston, have produced a magneto-electric type printer, which is very highly spoken of, and is largely used for private lines. Another form of instrument I saw was Edison's automatic apparatus, which has been extolled to a large extent as producing wonderful results, but it is not an instrument that works well except on short circuits. It is used by the Atlantic and Pacific Company, and, though it was worked to its utmost limit for our inspection, we did not get more than 200 words per minute out of it. It depends upon an electro-magnetic shunt; but sooner or later I have no doubt it will receive some extension.

Since we were there we have had introduced to us that very wonderful instrument the telephone. I saw it when it was first introduced; since then it has received a large amount of attention in America, where a great number of instruments are in use, and it has created a sensation here which is likely to continue for some time to come.

Some of the technical terms used in America are peculiar. A poor operator is called a "plug." To stop a message is to "break." If an operator cannot call a station it is said he cannot "raise NY." Contact between wire and wire is called "crossfire." Connecting one line across to another is "flipping ;" working off business is "rushing;" and when a message from an intermediate station takes off a message at the same time that it is being sent to the terminal the wayside station takes a "drop copy." If there is a great pressure of messages "biz is piled up." If a wire works badly it is "a rocky wire." If the current fails the battery "loses grip." When a wire breaks down it is "busted;" if it is faulty it is "in trouble." An intermittent contact is "a swinging cross." Forms are "blanks." There are other terms very peculiar, but to us not very expressive, because we are not acquainted with them. There are various peculiar accidents which telegraph lines in America suffer from. One is the falling of trees on forest lines in winter and another is lightning in summer. Forest fires are a great source of trouble, and they suffer more than we do from snow and sleet storms. However their electrical condition is so perfect and the climate so favourable to the working of wires that these exceptional cases of break-downs do not trouble them so much as they would trouble us, and I was surprised to find that they do not suffer from lightning so much as we do here. I attribute that to the fact that our system is more concentrated, and to the little thunderstorms we have rarely occurring without affecting our wires and damaging our instruments; but in that great country they may have fifty storms and not one pass over the telegraph wires.

I should have liked to have said much about the construction of their workshops. One distinguishing feature is the almost total absence of mechanics; the practical skill of the operators renders it unnecessary to keep mechanics.

They have in America a large telegraph business in ship-signalling. The arrival of mails is looked for with great interest, and they have carried the signalling to a high pitch.

I have alluded to the military telegraph stations. They have 145 stations all over the country, and, as I have mentioned, these stations are used to a large extent for meteorological purposes. They watch the rise and fall of rivers, and they give notice to farmers of the approach of thunder and wind storms; in fact the transmission of these observations is doing a vast amount of good.

Then there is time-signalling there. The time at Washington is sent to I don't know how many different places.

I am now going to tell you something which I am sure you will not believe, because the results appears so incredible. There are fire alarm apparatuses all over the towns. Wood being used to a large extent in building, when a fire occurs, unless the engines are quickly on the spot, the building soon comes to grief. The conditions of building are so different to ours, that, whereas we should have difficulty in setting fire to a house, a slight spark might cause a disastrous conflagration in America, and it is this which renders necessary the wonderfully rapid system of fire alarms that has been established there. The consequence is that the most elaborate and beautiful system of fire-signalling is established in every town. Wherever a fire occurs, a person pulls a handle which rings a bell at the fire stations, indicating the spot; this is immediately transmitted to the other fire stations, and the engines arrive and the fire is mastered before it has got ahead. I have not found anyone who will believe what I saw. We inspected one of the fire signalling stations in New York, and an alarm was raised. The gong sounded, the men turned out, the horses were unhitched and rushed to their places at the engine, and all was ready to start in eight seconds! We took three observations of these exploits; the first was eight seconds, the second seven seconds, and the third nine seconds, so that on an average of eight seconds this operation was performed. It is recorded that in one instance there was a fire one-third of a mile from the station. The alarm was given, the horses were released and hitched up, and the engine was off and was playing on the fire in one minute forty seconds.

In Chicago this system is carried further. Not only does the sounding of the alarm release the horses ready for putting to on the engine, but in a room above there is a long sleeping place for twelve men. At the foot of the driver's bed there is a trap-door. When the alarm is sounded every horse is unhitched, and runs to its place: the bed-clothes are whipped off every man: the trapdoor falls, and the driver slides down into his place! I saw that done: I did not take the time, but I believe it was all done in six seconds. They even go further than that. They do not require to see smoke and flame issuing from a building, but they have automatic alarms there, which are set in motion by the warmth of the atmosphere, which causes contact to be made, and communicates the alarm to the fire station without intervention on the part of anybody.

I must say one word with regard to domestic telegraphs. They carry their telegraph system to a pitch of perfection that we cannot understand. There is scarcely a private house in New York of any pretensions, or indeed in any town of over 20,000 inhabitants, which has not its call-box in the hall or in the office for the transmission of orders. Supposing you want a messenger to fetch you tobacco, or a carriage to take you to the theatre, or supposing you are ill and want a doctor, or are attacked and want the police, all you have to do is to put an index to "doctor," or "messenger," or "police" and start a handle. It immediately rings a bell at the central station, which indicates the street and number of the house as well as the message. In this way the telegraph in America is made subservient to the comfort and conveniences of social life.

I pass on however to speak of the organisation of the telegraph system. It is largely characterised by great elasticity. There is a total absence of that routine which is such a bugbear to our conservative system. Every man is allowed to act upon his individual responsibility, and he is allowed great latitude in carrying out his business. The result is, the service there is a genuine service, and you never find there a man discharging his duties in a perfunctory manner. Every man knows that his success in life depends upon his own exertions—he does his work with a will.

It has been said of us that we stand with our hands in our pockets waiting for inventions from America. That is not true. We do a good many good things ourselves, but it is not our fashion to blazon them forth. One reason however why inventors come to England is this—in America invention is a profession, men are paid there to invent. The Western Union have in their employ one of the cleverest practical electricians of the age—Mr. Edison. He is furnished with a magnificent laboratory, his only duty is to invent, and if he did not invent he might lose his employment sooner or later. More than that, people are encouraged to invent. A man shadows forth a thing—if it is promising, everything is put at his disposal and all is done to encourage him. Every new thing is freely published, and the patent laws are sound and within the reach of all. In England, on the contrary, an inventor is looked upon with horror—as something to be avoided, and the patent laws are execrable.

I do not draw comparisons between the systems of America and England. The fact is, neither system can be said to be in advance of the other. We have all of us worked in different grooves, but we have all had the same goal in view, and the same results have been obtained. We have all striven with might and main to acquire first of all rapidity in the transmission of messages; secondly, to increase the capacity of wires for the transmission of messages; and thirdly, to improve facilities to the public. In America the increased capacity of wires has been obtained by improving the "sounder" and adding all the wonderful advantages of multiplex telegraphy. We in England have had to do the same thing by perfecting the automatic system of Bain and Wheatstone, and we have been able to do some good things in England with the automatic process. Facilities to the public have been increased, but not, as in America, with good financial results. If the Postal Telegraph Service had been conducted upon strictly financial principles perhaps some hundreds of our villages would never have had the advantages of the telegraph, they would have been left out in the cold. In America telegraphs are made to pay, and no office is opened that does not pay.

There are no doubt many "wrinkles" to be derived from what we saw done in America. We have recently been visited by two distinguished Americans, who have no doubt gained some "wrinkles" from us. Mr. Fischer and I have come back with "wrinkles" gained from them, and I am quite sure that mutual benefit must ensue from mutual intercourse between two such countries as England and America. (Loud applause.)

SIR CHARLES BRIGHT rose and said: I am quite sure I express the feeling of those present when I propose a very cordial vote of thanks for the interesting, graphic, and eloquent address which Mr. Preece has favoured us with. I have been in America, and have seen something of the telegraph system there, but I can add nothing to what has already been said. if the time was not so limited I could have said a few words with regard to the social aspects. I have myself slept well in the Pullman cars, and I don't like the hotels which Mr. Preece praises. If there is any discussion on the subject at a future time I should like to say a few words with regard to the "sounder" apparatus and insulators; but I will leave that to another time, and content myself now with proposing a vote of thanks to Mr. Preece. I should like Professor Hughes to second it, if he will.

Professor HUGHES: I very cordially respond to Sir Charles Bright's suggestion that I should second the motion. I have been very much delighted at listening to the address, and I beg to acknowledge the kind remarks which the author has made with reference to what little I may have said or done myself.

The PRESIDENT: I feel as if I had hardly got breath to put this motion to the meeting. I confess Mr. Preece has taken the breath out of me, not only by the vast mass of matter no less than by the perfectly true statements he has made. (A laugh.) One is, however, happy to find that the amount of go-a-headedness which he seems to have acquired in the healthy and crisp atmosphere of America has not deserted him yet, and he is evidently in a fit condition to give us just such another lecture as he has already delivered. We had an account of the quadruplex system in this Society about a year ago, and it was then talked of as a perfectly experimental system. Mr. Preece promised to bring us detailed information with regard to the working of that system, but he has only been able to touch upon it so far as to say it is working successfully. The question of testing, which has been carried out in a remarkable way, and also that of insulators, is a very interesting one, and affords matter for separate discussion, and if we could have the opportunity of putting Mr. Preece on the rack again at a future time I am sure it would not only be to our advantage here but to the advantage of the profession generally in this country and also on the other side of the water.