[Trade Journal]

Publication: The Electrician & Electrical Engineer

New York, NY, United States

vol. 6, no. 4, p. 131-133, col. 1-2

THE STORY OF THE WORD "TELEPHONE."

BY THOMAS D. LOCKWOOD.

In a little book which I perpetrated in the year 1882, there was a chapter entitled "Facts and Figures about the Speaking Telephone." I made the rash statement in the opening paragraph of that chapter, that "The first record of a sound transmitting instrument in connection with which the word 'telephone' occurs, is believed to be the English patent of Sir Charles Wheatstone, No. 2,462 Oct. 10, 1860." This statement was strictly true. Such was at that time my belief.

The book in question was reviewed by the British Telegraphic Journal and Electrical Review and the above statement was commented upon as follows:

"We fancy the use of the word 'telephone' as a sound transmitter dates considerably farther back than 1860. Indeed, some of our readers may remember the well-known 'telephonic concerts' of Sir Charles (then professor) Wheatstone, given at the now defunct Polytechnic Institution very many years back, in which musical sounds were transmitted a considerable distance through wooden rods."

This comment, together with a consideration of the numerous and frequent absurd statements made by zealous advocates of the multitudinous claimants to the inventorship of the speaking telephone, determined me to find out what was discoverable in the matter, and to bring together in the pages of this magazine the result of my researches.

How frequently we hear, that "it is simply impossible that Professor Bell intended to patent or describe the speaking telephone in his 1876 patent; if he had he would have entitled it "telephone," whereas, he simply called it "telegraphy." Then on the other hand, we are gravely told that "Professor Bell was well aware before his invention, patented March 7th, 1876, that speaking telephones were well known to every one, or he wouldn't have referred to them by that name in a prior application for patent in harmonic telegraphy." Of course the wish with these advocates is very nearly related to the thought. It is, however, perfectly obvious to all who take thought in such matters, that the mere name of any invention is an immateriality; in this case, glaringly so; for the name is evidently applied to its present use simply for convenience; its very etymology indicating the true meaning; viz, "sound from afar," — and of course it is equally easy to see that sound is not restricted to speech. With reference to the inference that some wish to draw from the circumstance that Professor Bell's patent is entitled "An Improvement in Telegraphy", it is only, I think, necessary to point out that the term "telegraphy" had from usage grown to be generic; and it was equally as reasonable to apply it to a speaking telegraph, as it was to the strokes of a sounder, or the visual indications of a Cooke and Wheatstone needle, or a Bright's bell instrument, none of which made a written or graphic record of their signals.

I will now give an abstract of the information which I have accumulated on this head.

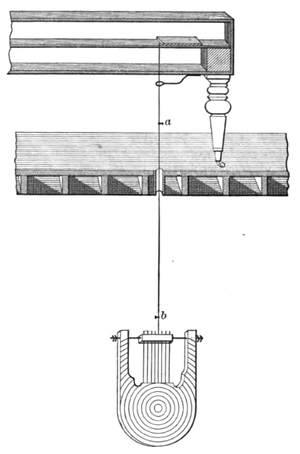

Prof. Wheatstone, at quite an early period of the present century, was a persistent and energetic experimenter in the transmission of sound through solid bodies, and in 1821 succeeded in transmitting music "with all the varieties of tune, audibility and all the combinations of harmony unimpaired." He exhibited what he called "The Enchanted Lyre," and so perfect was the illusion in this instance, from the intense vibratory state of the reciprocating instrument, that it was universally imagined to be one of the highest efforts of ingenuity in musical mechanism. As a matter of fact the mechanism was of the simplest character, comprising only an ordinary lyre of eight strings, suspended by a wire extending through the floor from the sounding board of a pianoforte in a room above. The accompanying figure shows the arrangement,

These researches are recorded in the Literary Gazette, 1821; Ackerman's Repository of the same year; in a scientific paper written by Wheatstone himself for Thomson's Annals of Philosophy, 1823 ; vol. vi, pp. 81-90; and in a paper written also by Wheatstone for the Journal of the Royal Institution, 1831, vol. 2. The last paper records among other things, the much repeated observations of Robert Hooke, on communicating through a distended wire; and concludes with these remarkable words: —

"The transmission to distant plactes, and the multiplication of musical performances are objects of far less importance than the conveyance of the articulation of speech. The almost hopeless difficulty of communicating sounds produced in air with sufficient intensity to solid bodies, might induce us to despair of further success; but could articulations similar to those enounced by the human organs of speech be produced immediately in solid bodies, their transmission might be effected with any required degree of intensity. Some recent investigations lead us to hope that we are not far from effecting these desiderata; and if all the articulations were once thus obtained, the construction of a machine for the arrangement of them into syllables, words, and sentences, would demand no knowledge beyond that we already possess."

|

It is to be noticed that the idea that articulations might be transmitted and reproduced by the agency of electricity does not seem to have occurred to Prof. Wheatstone.

Before dismissing Professor Wheatstone's own papers, it will be interesting to note that in October, 1837, he compiled an article for the London and Westminster Review, in which he gave an account of the several attempts which had up to that time been made to imitate the articulations of the human voice by mechanical means; and that this article concludes with the paragraph "There are no doubt a great many difficulties yet to be contended with, before we can succeed in perfectly imitating the articulations of speech; but the partial success of the attempts of which we have laid an account before our readers, ought to encourage further trials. It is not too much to say in the words of Sir David Brewster, 'We have no doubt that before another century is completed, a talking and a singing machine will be numbered among the conquests of science.'"

It is also interesting to note en passant that Professor Wheatstone devised a mechanical instrument (which he describes in the Quarterly Journal of Science for 1827) for rendering audible the "weakest sounds, to which he gave the name of microphone.

I have been somewhat disappointed to find that in these papers Wheatstone himself does not employ the word "telephone," although there is reason to believe that he was in the habit of referring to his appliances for transmitting sound by that name. In a work entitled "Posts and Telegraphs, Past and Present," published in 1878, I find the following amusing anecdote of Sir Charles Wheatstone's acoustic performances, given by a Mr. William Chappell: "An eminent foreign performer on the violincello came to England, bringing a letter of introduction to Wheatstone. He left the letter at the house, and made an appointment to call at a particular hour on the following day. Wheatstone was at home to receive him, and thinking to surprise and amuse his visitor, hung a violincello on the wall of the passage, having a rod behind it to connect it with another, which was to be played from within when he entered the hall. The guest turned in every direction to find whence the sounds came, and at last approaching the violincello hanging on the wall, and having satisfied himself that they proceeded from it, although there was neither hand nor bow to play upon it, he rushed out of the house in affright, and would never enter it again."

In Timbs's Year Book of Facts in Science and Art, for 1845, is found on page 55, this item:

"THE TELEPHONE."

"Captain John Taylor has invented this powerful instrument for conveying signals during foggy weather by sounds produced by means of compressed air forced through trumpets; audible at six miles distance. The four notes are played by opening the valves of the recipient, and the intensity of sound is proportioned to the compression of the internal air. The small sized telephone instrument which is portable, was tried on the river and the signal notes were distinctly heard, four miles off. The instrument is engraved in a late number of the Illustrated London News."

The next published instance of the use of the word "telephone " occurs in the same journal — Timbs's Year Book of Facts; but for the year 1854.

It is entitled "New Telephone" and reads: — "A very curious system of telephony for the transmission of language at great distances by means of musical sounds has been invented by M. Sudre, at Paris. The plan consists in making use of three notes placed at given intervals; and which when combined or repeated according to certain rules, are capable of rendering the most complicated sentences. Thus one of the company writes a few lines, and on M. Sudre reading them, he strikes his three notes alternately according to his method, when a third person without any previous knowledge of the writing repeats the words merely from hearing the notes. The system has been, it is understood, tried on a very extensive scale to test its applicability to naval and military purposes, and it is stated fully to justify the high enconiums the French Institute and other scientific bodies have bestowed on it."

At this epoch we find that Wheatstone once more crops up.

Referring again to the little book — "Posts and Telegraphs" by Tegg; London, 1878, page 290 I find the following: —

"On the 10th of May, 1855, an exhibition took place before Her Majesty the Queen, at the Polytechnic Institution, of which the only account that has been reproduced is that given by Mr. C. K. Salaman, in a letter to the 'Choir': —

"1. Lecture by J. H. Pepper, Esq., on Professor Wheatstone's experiments on the transmission of musical sounds to distant places, illustrated by a telephone concert, in which sounds of various instruments pass inaudible through an intermediate hall, and are reproduced in the lecture room, unchanged in their qualities and intensities."

The sounds produced in a lower room were carried through a wooden rod to the lecture room.

Prof. J. H. Pepper describes this occurrence in his "Cyclopedic Science Simplified," London, 1869.

In 1871, in a course of lectures on sound, Professor Tyndall repeated this illustration; and the repetition is recorded in the Journal of the Society of Arts, vol. 19.

We now arrive at Wheatstone's British patent, No. 2,462, of 1860, in which he claims among other inventions —

"The employment of musical pipes or free tongues acted upon by wind in the construction of telephones, in which the alternation of long and short sounds are grouped in a similar manner to the long and short lines in the alphabet of a Morse's telegraph; or in which two sounds are made to succeed in the order of the alternate motions which constitute the alphabet of a single needle telegraph."

The next example is the telephone of Philipp Reis: — "I give to my instrument the name telephone," vide Jahresbericht of the Physical Society, Frankfort, 1860-1861.

The name was then applied almost exclusively to this instrument from this time until the advent of the speaking telephone.

In February, 1875, Mr. Alexander Graham Bell used the word to indicate a vibrating receiver in a system of harmonic telegraphy, and describes it in these words "For instance, with a series of transmitters I can place at the receiving end of the line a telephone from the rod of which silk threads may lead to a series of bodies such as tuning forks capable of definite vibration, each one of these bodies having a rate of vibration corresponding to one, and one only, of the transmitters. In case two or more different sets of impulses be transmitted simultaneously to the telephone, each will affect that one alone of the tuning forks whose vibrations are synchronous with the impulses. The same effect could be produced by resonators of different pitches placed under the rod of the telephone."

And during the years 1875-1878 Elisha Gray applied the term "telephone" to his entire harmonic system — vide U. S. Patent No. 175,971, April 11, 1876, Telephonic Telegraphs; "A New and Practical Application of the Telephone," by Elisha Gray — Journal of the American Electrical Society, 1877. "The Telephone, the Microphone and the Phonograph," Du Moncel, Paris, 1878, "Electricity and the Electric Telegraph," Prescott, 1878, pp. 868-880; and the Gray and Bell correspondence in February, 1877, (Dowd Case, vol. l, pp. 146-147), in which Mr. Gray says "I gave a lecture in McCormick Hall, this city (Chicago), Tuesday evening, 27th inst., on the telephone, as I have developed it. I also connect with Milwaukee, and have tunes and telegraphing done from there."

The term "telephone" seems to have been applied by Mr. Bell in his paper before the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, May 10, 1876, to harmonic and speech receivers and transmitters indiscriminately; but referring once more to the Gray and Bell correspondence we find that Mr. Bell has, under date of March 2d, 1877, reached a point where "telephone" for him has but one meaning. He says, "I have not generally alluded to your name in connection with the invention of the electric 'telephone,' for we seem to attach different significations to the word. I apply the term only to an apparatus for transmitting the voice (which meaning is strictly in accordance with the derivation of the word), whereas you seem to use the term as expressive of any apparatus for the transmission of musical tones by the electric current."

Thus we see that the word "telephone" is not a new word, but that it has in the past been used in a variety of ways.

It seems to me, therefore, that the definition given to the word in Knight's American Mechanical Dictionary is a fair and pertinent one. This is "TELEPHONE, an instrument for conveying signals by sound. It may consist of a steam whistle, a fog trumpet, or other audible alarm. The term, until lately, has been particularly applied to a signal adapted for nautical or railroad use, in which a body of compressed air is released from a narrow orifice, and divided upon a sharp edge in the manner of a steam whistle. The term is now acquiring a different signification."

However, since the Centennial exhibition of 1876, the application of the term to an apparatus for the transmission and reproduction of speech has become well nigh universal; and every other meaning seems to be totally superseded.

I have thought it worth while, therefore, to make a compact record of the instances of its use otherwise which I have been able to find.