[Trade Journal]

Publication: Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts

Winston-Salem, NC, United States

vol. XXII, no. 2, p. 1 - 39

The Southern Porcelain Company of Kaolin,

South Carolina: A Reassessment.

J. GARRISON STRADLING

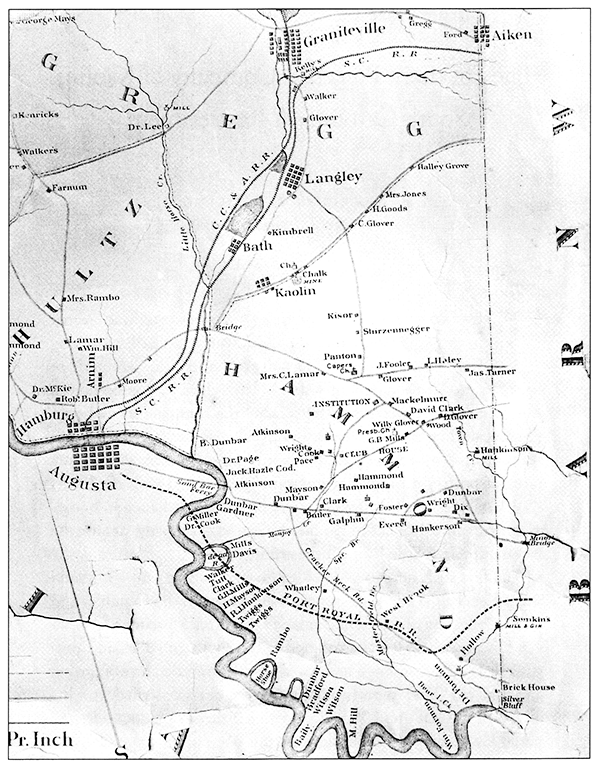

THE SOUTHERN PORCELAIN COMPANY was created in 1856 and, until after the Civil War, it utilized white clay from the Edgefield pottery district of South Carolina (see fig. 1) to produce a variety of wares. Of this there can be no doubt. But speculation concerning what exactly the company made began to swell during the next century until, like sightings of UFOs and sea monsters, it burst beyond the bounds of reason. Nowadays, and piece of pottery or porcelain impressed or stamped with the letters "S. P. Co." is apt to be offered for sale by dealers and auction houses as an authentic product of the South Carolina company, despite the fact that there is little basis for the attribution.

|

1. Detail from the Isaac Boles map of 1871, showing the old Edgefield District and the Southern Porcelain Company buildings at Kaolin, below Bath, South Carolina. Courtesy of the South Carolina Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia. MRF 21,589.]

The first such questionable object to find its way into a museum was a Rebekah at the Well (1) earthenware teapot in the Ceramics and Glass Collection of the Smithsonian Institution's Museum of American History, where it was attributed to the Southern Porcelain Company. It is 4¼ inches high and covered with a mottled brown, green, and dark red glaze. Impressed on its bottom in fancy serifed lettering are "FIREPROOF" and "S. P. Co." with a little ditto mark under the raised lower case "o." Over the years this one teapot, more than any other object, fueled the belief by curators and collectors that all relief-decorated earthenwares marked "S. P. Co." had been made by the Southern Porcelain Company.

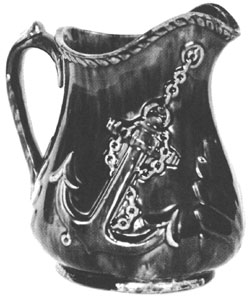

In museums across the country, labels began to appear on a succession of Rockingham-glazed tablewares, including a water pitcher with an anchor and chain on either side (fig. 2); a teapot with a seated Chinaman holding a fan, faced by another smoking an elaborate pipe, his back to a stack of tea canisters topped by a tall teapot with a wreath enclosing the bust of a man who might be George Washington. They were impressed "S. P. Co =" or "S. P. Co" on their undersides in plainer, sans-serif letters (fig. 4).

|

2. Rockingham-glazed water pitcher with anchor and chain decoration, earthenware, bearing the impressed mark in bottom: "S. P. Co =". HOA 9". Private collection; photograph Jay A. Lewis.

|

3. Rockingham-glazed teapot with Chinese decoration and notched foot rim, earthenware, impressed mark on bottom "S. P. Co =". HOA 6 3/8". Private collection; photograph Jay A. Lewis.

|

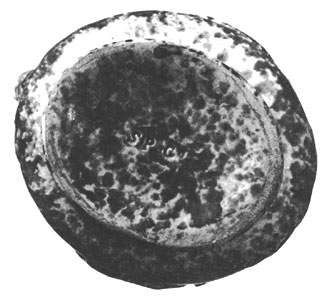

4. The "S. P. Co =" mark, most commonly found on Rockingham-glazed earthenware. Private collection; photograph Jay A. Lewis.

As my wife Diana and I examined a number of these objects in institutions across the eastern United States, the more we saw, the more our suspicions grew concerning their origins. Over a period of some twenty years, we had traveled through the South in search of rare ceramics, in particular some piece of porcelain bearing the mark of the Southern Porcelain Company. We pleaded to be pointed at any museum or private collection where such a treasure might be housed and made it clear to every local dealer or picker we met that we would pay handsomely for even a translucent shard with the company mark. We heard many legends of "something seen by somebody sometime back," but beyond that, silence.

Both of us were familiar with what had been made by earlier and contemporary porcelain companies in America, such as the Tucker works in Philadelphia (1827 - 1838) and the factories of Charles Cartlidge (1848-1856) and William Boch and Brothers (1852-1857) on Long Island in Greenpoint, New York. But as far as we knew, none of these factories had produced Rockingham ware. On the other hand, the United States Pottery Company at Bennington, Vermont (1853-1858), had made both Rockingham ware and porcelain, but never called itself a "porcelain company." Why, then were the only marked survivals to be found from the Southern Porcelain Company pieces of Rockingham-glazed pottery?

In addition, the relief designs on these Rockingham tablewares marked "S. P. Co." were similar to or the same as those on products of several eastern manufacturers in a date context of the late 1870s and even the 1880s, long after the Southern Porcelain Company stopped making either pottery or porcelain. The distinctively daubed colors, and especially the use of red on the Smithsonian's Rebekah at the Well teapot, were characteristics we had only encountered on late nineteenth-century pottery from South Amboy and Mattawan, New Jersey. We had even seen turn-of-the-century semi-vitreous porcelain and ironstone, bearing a variety of black-stamped or transfer-printed "S. P. Co." marks on their bottoms, that had been attributed to the South Carolina firm. Therefore, so that suffering collectors might be healed of and future generations protected from "S. P. Co." fever, this reassessment of the factory and its wares has been undertaken.

THE HISTORY OF THE

SOUTHERN PORCELAIN COMPANY

To date, no one has improved on the history of the Southern Porcelain Company written by Edwin AtLee Barber for the first edition of The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, published in 1893. His account, prepared at a time when many of the old potters and managers were still alive, may be regarded as a canon against which to measure the statements and theories of others. (2)

According to Barber, the Southern Porcelain Company of Kaolin, South Carolina, was founded in 1856 by one William H. Farrar, previously a stockholder in the United States Pottery Company of Bennington, Vermont. Farrar had the backing of prominent Georgia citizens from nearby Augusta and elsewhere, including Alexander H. Stevens, who later served as vice president of the Confederacy. To construct the factory, Farrar brought with him brick masons from Vermont, who erected "the most approved kilns of that day," and Anson Peeler, a master carpenter, who had built the Bennington pottery.

Barber states that the first manger of the company, an inept Englishman, was quickly replaced by Josiah Jones, "a skillful designer and competent potter" who had previously modeled for his brother-in-law, Charles Cartlidge, at Greenpoint. What Barber describes as "very fair porcelain and good white granite and cream-colored wares" were produced but without commercial success, largely because Farrar insisted on the exclusive use of local clays. In the fall 1857, Farrar appealed to his former colleagues at Bennington and arranged for Decius W. Clark, a brilliant scientist who was considered one of the foremost stoneware potters in the United States, "to take the South Carolina potteries in hand." In February 1858, the senior Clark returned to Vermont and was replaced in Kaolin by his son Lyman W. Clark, who took charge of the preparation of bodies and glazes. (3) Barber reports that in 1860, manufacture of the finer grades of ware was discontinued.

At the outbreak of the Civil War the company was reorganized as the Southern Porcelain Manufacturing Company, which, Barber states, "is said to have gone into the extensive manufacture of porcelain and pottery telegraph insulators for the Confederate Government." Figure 5 illustrates a firebrick from this period. The factory also produced earthenware water pipes, in the face of the inexorably turning tide of the war against the southern cause, in its efforts to remain solvent. (4)

|

5. Firebrick made by the Southern Porcelain Manufacturing Company, c. 1861 - 1864. LOA 8⅞". Private collection. MRF 21,530.

In 1864, an apparent infusion of capital and an article in an Augusta newspaper suggest yet another reorganization. (5) The Daily Chronicle and Sentinel reported on 22 April 1864 that the company's agency in Augusta was at 189 Broad Street under the management of J. E. Marshall, and that the factory was currently making "insulators, battery jars, porous cups, fire brick, retorts, jars, gallipots, furniture for hospitals and chamber purposes, articles for domestic use, plates, cups, saucers, pitchers."

On the night of Thursday, 13 October 1864, a fire was discovered issuing from the engine room of the Southern Porcelain factory. Despite efforts to extinguish the blaze, it spread quickly and destroyed the entire works. The 15 October Daily Chronicle and Sentinel estimated the loss at $200,000 and said the insurance amounted only to $25,000. (6) If the speculations of W. H. Farrar in the Edgefield District had not already ended with the outbreak of the war or in one of the company's reorganizations, they most assuredly went up in smoke on that fateful night.

THE ELUSIVE W. H. FARRAR

Just who was W. H. Farrar? Mary E. Davison, in her article on William H. Farrar in the March 1939 issue of The Magazine ANTIQUES, said he was a potter who had established a successful Rockingham and stoneware manufactory in Geddes, New York, in the 1840s, sold out in the late 1850s, and went south to found the Southern Porcelain Company. (7~~) Yet the question remained, how could such a successful mango to South Carolina and self-destruct?

In the 1850 U. S. census for Geddes, New York, W. H. Farrar and his Stoneware Pottery appear at the bottom of page 486 with his name misspelled "Farrier." At the time, Farrar was thirty-seven years old and had been born in Vermont. His wife Jane was listed as a native of Canada, and his only son, George, aged five, had been born in New York.

In the 1860 census for the Edgefield district of South Carolina, W. H. Farrar is listed as a "Mechanic," forty years old and from New Hampshire. His wife, Laura, had been born in Florida. Both their fourteen-year-old daughter, also named Laura, and their twelve-year-old son, George P. Farrar, had been born in New Hampshire.

Allowing for the ten-year difference between the census reports, the W. H. Farrar of Geddes was seven years older than the Farrar of Edgefield, which settles the matter once and for all. These were two different men. Barber had clearly stated in his book that the W. H. Farrar who went to South Carolina was not a practical potter, but later writers chose to disregard that description.

Both W. H. Farrars had descended from Jacob Farrar, who arrived in Lancaster, Massachusetts, from England around 1658, married ten years later, and was killed by Indians in 1675; the last ancestor they had in common was Jacob's son, George (see Appendix I). Three generations later, most of the family was still living around Concord, Massachusetts, or New Ipswich, New Hampshire, where the men were employed as doctors, clergymen, and gentleman farmers; around the turn of the eighteenth century, three sons of the minister Stephen "Priest" Farrar decided to become potters and went to Vermont. Reverend Farrar, a grandson of George, had been a classmate of John Adams at Harvard and more than a hundred years later was remembered as "Pastor Patriot Counsellor" for his role in the Revolution. His eldest son, Isaac B. Farrar, established a pottery in Fairfax, Vermont, and died there in 1838. His numerous children, all raised in the potting profession, carried their skills across New England and into upper New York State and Canada. Samuel Farrar also moved to the Fairfax area, and Caleb Farrar founded a pottery in Middlebury, Vermont. W. H. Farrar of Geddes, New York, was doubtless a son of one of these three men. (8)

The W. H. Farrar who founded the Southern Porcelain Company was William Henry, son of physician George Farrar, who was in turn the second son of Humphrey Farrar of New Ipswich. He was born in Derry, New Hampshire, on 24 February 1820, married Laura C. Jones on 4 July 1843, and according to a memoir of the Farrar family published in 1853, was then a merchant, living in Boston. (9)

Interestingly enough, there was another W. H. Farrar in Boston at the same time, William Henry's cousin William Humphrey Farrar, a lawyer, or "counselor" as he was called in the 1852 Boston City Directory. He was the son of William Farrar, fifth son of Humphrey Farrar. So by 1852 three W. H. Farrars could be accounted for — and there would be more.

FARRAR, BENNINGTON, AND

SOUTH CAROLINA CLAY

In 1852 William Henry Farrar, the Boston merchant, became financially involved with the Bennington Pottery, a company in the throes of reorganization and approaching its pinnacle of glory as it prepared an impressive display for the New York Crystal Palace Exhibition. Unfortunately, the pottery's dynamic founder, Christopher Webber Fenton, and his chief financial backer, attorney A. P. Lyman, had become encumbered with liabilities beyond their means; therefore, on 10 April 1852, they deeded to Lyman Harrington and Calvin Park the company's assets, including real estate and a large amount of unsold ware, much of which was being kept for sale at a store in Boston. By this action, they secured their debts and remained as silent participants in the pottery's affairs.

Harrington and Park arranged with William H. Farrar to take over "possession and management" of the Boston store in order to dispose of Lyman and Fenton's unsold pottery, as well as whatever other wares that they might send to him. Farrar served as their general agent in Boston for less than a year. On 12 January 1853, business at the store was discontinued, and Harrington and Park, "by the advice and direction" of Lyman and Fenton, conveyed their assets to Farrar, O. A. Gager, and Henry Willard, who continued to carry on the "pottery business at Bennington and afterwards organized the corporation under the name of the U. S. Pottery Company. (10)

At the opening of the Great Exposition of 1853 in New York City on 2 May, the wares of the U. S. Pottery Company made a greater impression on reporters covering the event in the following weeks than anything else displayed by manufacturers of American ceramics. Most writers praised the gaudy "flint enamel" glazes on Bennington earthenware, but some also recognized the significance of tits porcelain. Kaolin had been discovered in Vermont early in the century, but only C. W. Fenton had been able to use it successfully to make porcelain, beginning around 1847. According to one contemporary publication, Fenton was using flint from Vermont and Massachusetts, feldspar from New Hampshire, and china clays from Vermont and South Carolina. (11) Fenton and Decius Clark had prospected in South Carolina sometime between 1847 and 1851 and located extensive deposits of porcelain clay. They had huge quantities of this material dug out, wheeled into a drying oven, and shipped north as ballast for cotton shipments, finally to be used by the Bennington pottery. (12)

By 1854, the U. S. Pottery Company consisted of William H. Farrar, O. A. Gager, Henry Willard, Jason Archer, and S. H. Johnson. On 9 December, however, Farrar sold his fifth share of the pottery's assets to C. W. Fenton for $13,000, (13) represented in part by the transferal of approximately 26 acres of land near Bath, South Carolina, containing a kaolin bed, the deed to which was held by A. P. Lyman. A value of $3,500, placed on the property by Decius Clark, was agreed upon by both parties. By the contract of sale, Farrar held a mortgage on Fenton's fifth share until this property was turned over to him. He also had a letter from Fenton promising to procure and provide him with "a good and valid warranty deed," executed according to the laws of the state of South Carolina. Otherwise, he could foreclose the mortgage. (14)

Dreams of making porcelain had inflamed the minds of men for centuries, and in the eighteenth century, a white clay known to the Cherokee as unaker caused speculators to comb the countryside in and around their lands. Andrew Duche, a potter working in Charleston, South Carolina, and then Savannah, Georgia, had prospected there and up the Savannah River as far as New Windsor, close to Kaolin, South Carolina. In 1743 he sailed for England and may or may not have taken with him specimens of the kaolin that was later exported to the Porcelain Manufactory at Bow. (15)

Although others might have previously used South Carolina clay as an ingredient for porcelain, Farrar had seen with his own eyes what could be made from it at Bennington. He was convinced that Fenton's clay would be the foundation for his path to fame and fortune. So, in 1856, after preliminary investigations, he packed up his family and headed south, only to become almost immediately embroiled in a dispute over ownership of the clay bed that would endure for as long as he remained in Kaolin.

Farrar's property, containing the kaolin bed, had formerly been owned by D. J. Walker and A. J. Rambo. It was described as follows: "Beginning at the S. E. corner of said lot and the North line of land owned by Charles Sampson, thence running westwardly on the North line of said Sampson's land sixty four rods; thence on right angles easterly sixty four rods to lands owned by Charles Powell, thence on Powell's west line sixty four rods to the place of beginning, making a square piece of land, twenty five acres and ninety-six rods." (16)

On the fourth Tuesday of December 1857, Farrar filed suit in the Court of Chancery at Bennington to foreclose his mortgage on the grounds that the deed he received from Lyman represented only half of the property, namely that which belonged to D. J. Walker; the other "undivided half" continued to be owned by A. J. Rambo. Farrar claimed he had only become fully aware of the situation while in the process of selling the land on 5 June 1856 to a stock company which planned to build a pottery on the property, and added that when Rambo heard of these plans, he made Farrar pay $2,500 in order to obtain his half. Farrar said he had repeatedly attempted to get the U. S. Pottery Company to reimburse him for the money and was refused. He therefore took the position that since he had not been conveyed a deed with a clear title to the entire property, he was empowered by law to foreclose. Subpoenas were delivered to C. W. Fenton and to the U. S. Pottery Company.

Various countersuits were filed, the earliest alleging that Fenton had never promised to deliver to Farrar a full and perfect title to the clay bed or to guarantee or be held responsible in any way for the validity of the title conveyed. A. P. Lyman admitted that his deed had been conveyed by Walker alone, but said Walker and Rambo were partners and acting together in the transaction, and that he had negotiated to purchase the whole clay bed with Walker, who was fully authorized to receive payment and to represent Rambo, who was to provide title to his half when he returned from a trip. Lyman stated that the deed was not only in order, but that he had even traveled to New York to make sure its transferal was executed properly according to the laws of the state of South Carolina. He said Farrar had accepted the deed and at the time instructed his attorneys to void the mortgage.(17)

On 8 May 1858, all pottery making ceased at the U. S. Pottery Company, and following the company's failure, Fenton and Decius Clark, possibly together with modeler Daniel Greatbatch, went south to see what was going on in South Carolina. (18)

Later that year, in a continuing response to Farrar's legal action, the U. S. Pottery Company's representatives attempted to shift the blame onto Fenton by claiming that he had originally hired an attorney to prepare a countersuit against Farrar, but that "Fenton, being now entirely irresponsible and insolvent and having gone to Bath, South Carolina and is there employed by the said Farrar or is in some way connected or associated in business with him," had withdrawn his countersuit and was instructing his attorney to try and obtain a decree in favor of Farrar. Further, they charged that Farrar's suit was "in reality prosecuted in the interest and for the benefit of said Fenton upon fraudulent collusion with Farrar" for the benefit of either or both.

Fenton and Clark had without a doubt originally intended to join up with Farrar, but after sizing up the potential of the Southern Porcelain Company within weeks after their arrival, they changed their minds. The potter Silas R. Wilcox, who moved from Bennington to Kaolin in December 1858, recalled in later years that when he arrived Fenton was still there, but soon afterward "went away, ostensibly to get supplies, etc., and never returned." Decius Clark left also, but sent his son Lyman W. Clark to South Carolina. (19) Fenton and Decius Clark extended their search for a suitable pottery site to Illinois, finally settling on Peoria, where they founded the American Pottery Company late in 1859. (20)

Eventually, the various countersuits against Farrar were combined into a single action by the U. S. Pottery Company, which was signed on 24 September 1860 by O. A. Gager, "Director and Formerly Treasurer and Agent" of the company. In this, the company stated that Farrar was actually indebted to Fenton for more than the $2,500 he claimed Fenton owed him. It was alleged that when Harrington and Park closed their Boston store, Farrar's books showed debts amounting to $7,000, owed by persons whose identities Farrar had refused to divulge despite repeated requests for this information by the company. Consequently, on 24 April 1857, A. P. Lyman and Harrington and Park had legally transferred to Fenton all claims they had to Farrar's debts. As Farrar was thereby indebted to Fenton for more than the $2,500 he had sought, the company deemed it unnecessary to honor his claim. Moreover, they argued that unless Farrar was prepared to settle his affairs, his suit should be dismissed. (21)

On 10 June 1865, in the absence of any further depositions by Farrar, who by that time was no longer in South Carolina, or by Fenton, who had died three days earlier in Joliet, Illinois, (22) the court meeting in Manchester, Vermont, dismissed Farrar's suit without prejudice to Farrar, and the U. S. Pottery Company was ordered to pay the court costs. The $2,500 claimed by Farrar was applied to his debt of Fenton, and the U. S. Pottery Company was empowered to recover its costs from Farrar, taxed at $114.71. (23)

FARRAR'S MANUFACTURE OF PORCELAIN

AND EARTHENWARE

The scarcity of surviving examples of porcelain made by the Southern Porcelain Company may be blamed on a number of factors. In addition to the legal difficulties faced from the beginning by the Southern Porcelain Company, the country was in the midst of an economic downturn that contributed to the cessation of most other porcelain manufacturing in America by 1857. Then, too, "Promoter Farrar," as one of the old Bennington potters called him, (24) had never been a potter and understood little about the practical aspects of making porcelain, despite whatever arcane information he may have been able to soak up while living in Bennington. This is why, like many American entrepreneurs who preceded him, he was seized by the mistaken notion that fine porcelain could be created form a single clay or group of clays from one location.

According to Farrar's statement above, the Southern Porcelain Company officially came into being on 5 June 1856. Then workmen began to arrive from Bennington: first carpenter Anson Peeler and his masons, and afterward potters, including mold-maker Enoch Barber who, like fifty-five-year-old Josiah Jones, had most recently been employed at Greenpoint, New York. (25)

At the time of the 1860 census for the Edgefield District, Peeler and his wife, Margaret, were 39 years old. Both had been born in New York State and left home before 1846. Their fourteen-year-old daughter Mary had been born in Massachusetts, and their nine-year-old son Irvey in Vermont. If, as Edwin AtLee Barber states, Peeler had built the Bennington pottery, it would have been when he was in his late twenties.

Peeler and the masons would have taken about two months to construct the pottery and kilns, so it is doubtful whether ware of any kind could have been made before fall 1856. In, in addition, the first attempts were failures and Josiah Jones was brought in quickly after these abortive efforts, we are left with a period of about three years during which fine porcelain could have been made while Farrar was in charge at Kaolin.

The only fully marked example of tableware known today from this period is a 7-inch-high molded creamer (fig. 6), which is not porcelain but a sophisticated whiteware. Impressed on the bottom is a diamond-shaped cartouche that surrounds an American eagle holding a cluster of arrows in its talons, with the words "S.P. / COMPANY" above and "KAOLIN / S.C." below (fig. 6a). Its embossed leaf design somewhat resembles that of a "graniteware" toilet set produced at Bennington (26) — so perhaps the vessel should more properly be described as a mouth ewer — but until it is proved to be part of a larger set, it must be considered a creamer. It was made from a mold, perhaps by Enoch Barber.

|

6. Fully marked Southern Porcelain Company creamer, whiteware, c. 1856 - 1860. HOA 6 11/16". Private collection; photograph by Jay A. Lewis.

|

6a. Detail of the mark on creamer in figure 6, reading "S. P. / COMPANY / KAOLIN / S. C." Photograph by Jay A. Lewis.

The only marked example of the company's porcelain found to date is a broken insulator with a clear lead glaze (fig. 7), impressed underneath with a shield containing the words "S. P. / COMPANY / KAOLIN / SC" (fig. 7a). It was discovered in an excavation in Richmond, Virginia, along with other unmarked insulators from the Civil War period. (27) A marked insulator in "brown stoneware" had been acquired by Edwin AtLee Barber for the Philadelphia Museum but was deaccessioned in 1954. (28) Both are in what collectors call a teakettle" or "teapot" shape. Barber was probably unaware of any other Southern Porcelain Company mark than what was stamped on the Philadelphia Museum's insulator. It is the only one cited in his book, Marks of American Potters. (29)

|

7. Fully marked Southern Porcelain Company insulator, porcelain with traces of clear lead glaze. HOA 3⅞", WOA 4" (base), 2¼" (top). Private collection. MRF S-23,185.

|

7a. Underside of insulator, showing the mark.

|

7b. Detail of the mark on the insulator shown in figure 7, reading "S P / COMPANY / KAOLIN / S C." Due to an optical illusion the mark appears to be raised, but it is actually impressed.

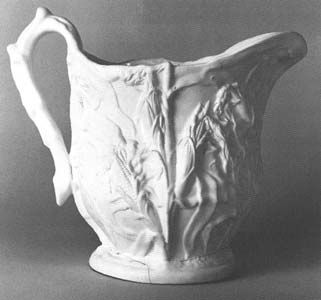

For attribution purposes, any fully marked object can be regarded ad "definite" — the creamer, once again, being all that is known in tableware. However, Barber pictured two other pieces of tableware, with no indication of whether or not they were marked, that have strong histories linking them to the Southern Porcelain Company in Kaolin. A Parian "wheat-head" syrup pitcher was purchased at the factory by Mrs. John S. Porcher of Eutawville, great-granddaughter of Richard Champion, the famous English porcelain maker who had emigrated to Camden, South Carolina in the eighteenth century. (30) A porcelain water pitcher with a corn or maize pattern had a history of being presented to Mrs. Edward Willis of Charleston when she visited Kaolin in 1861. (31) Since the whereabouts of these documentary examples are presently unknown, and without them to use for reference or comparison, similar objects found in the South cannot be positively attributed to the Southern Porcelain Company. They may only be considered "probables."

According to Barber, molds for both pitchers were brought from Greenpoint, New York, by their designer, Josiah Jones. (32) The corn-pattern pitcher could have been made as early as 1849 by Charles Cartlidge & Co., which produced them in at least six sizes, later by the Boch factory in Greenpoint, and by others. (33) Corn pitchers are by no means uncommon and when faced with a tableful of white porcelain corn pitchers, it is difficult to tell which was made where or by whom. They can also be found with a Rockingham glaze, and a glazed redware version is in the collection of the Henry Ford Museum. (34)

Figure 8 shows a large porcelain corn pitcher that was found in the South. It has a greenish translucency similar to Boch porcelain, but an unglazed exterior, unknown in Greenpoint pitchers. The bottom of its branch handle sticks out beyond the body and terminates in a vertical slice as if cut by garden shears, a characteristic also seen on the corn pitcher illustrated by Barber. Unfortunately, Barber did not give the size of the pitcher in his book; it may be smaller than the one in figure 8, since the mold details are markedly different. However, any 10-inch high porcelain corn pitcher with a cut-off handle terminal and the ears of corn in the same exact position as in figure 8 is probably a product of the Southern Porcelain Company. The same would apply to a smaller pitcher with details matching the one shown by Barber.

|

8. Corn or maize pattern water pitcher, porcelain, with unusual biscuit exterior and glazed interior, probably made by the Southern Porcelain Company, c. 1856 - 1860. HOA 10". Private collection. MRF-21,529.

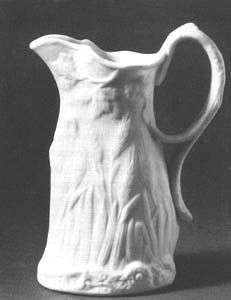

The wheat-head syrup pitcher in Parian ware (fig. 9) presents a different problem. Parian bodies are so alike that in the absence of a maker's mark it is impossible to distinguish between American and English Parian ware, much less between that of Bennington and the Southern Porcelain Company. (35) The design was probably inspired by a pattern called Ceres, registered by Edward Walley of Staffordshire in 1851, and although its mold may have come from Greenpoint, this little syrup pitcher represents the most sophisticated form believed to have been made at Kaolin. It is extremely rare and unlike anything in Richard Carter Barret's Bennington Pottery and Porcelain. (36) Therefore, after taking provenance into consideration, any example must be thought of as a "probable."

|

9. Wheat-head syrup pitcher, Parian ware, probably made by the Southern Porcelain Company, c. 1856 - 1860. HOA 4½". Collection of the Newark Museum, Newark, N. J., acc. 15.147. Photograph the Newark Museum / Art Resource, New York.

A recently discovered account of a visit to the factory, adds another object to the list of "probables" and gives us a glimpse of the Farrar family at home. Helen Zubly Clarke Bush (1826-1897) was a widow living in Augusta, Georgia. In the fall of 1859, while recuperating from a long illness, she made a trip to the Southern Porcelain Company factory. On Saturday, 3 September, she wrote in her diary:

I went to Kaolin in the Edgefield District, South Carolina. A few days ago, as it would seem, the old chalk hills were a part of nature's quietness. Now, due to man's inventive genius, the chalk is molded into pitchers, plates, bowls, and other articles too numerous to mention.

My kind and attentive friend Mr. Bridwell carried me there. We started about 10 o'clock in the morning and we had a very pleasant ride. It had been four years since I had crossed the Augusta bridge. There had been great improvement since I had been that road . . .

Mr. Bridwell pointed out eh chimneys of the manufactory to me. They were peeping out among the trees. We arrived at the manufactory, went through the lower floor, seeing the rough pieces of chalk. Then was to be seen large lumps of chalk of the consistency of putty. Then again we saw the chalk, molded into shapes ready for the kiln. The chimneys run through the factory like large pillars. The kilns have doors to them and look like dungeons that are inside old castles.

Then we walked upstairs to Mr. Farrar's office where I was introduced to a very pleasant gentleman in the person of Mr. Farrar, on every line of his face written mildness and goodness. He was pleased to see me and said to Mr. Bridwell, "So you have brought Mrs. Bush to see us."

He invited us to walk around and look at the ware which was already for sale. I saw many mugs, pitchers, goblets, bowls and pitchers, soap cups, jars, and may other articles of needful domestic goods. The company was out of their nice wares, no china of much value was on hand . . . After looking around the rooms Mr. Farrar said we must go up to the house and see Mrs. Farrar. I had seen their daughter Laura before, for she had called upon me. . . . After riding a few yards we came to Mr. Farrar's house. There is quite a large space before the house, which is built in the style of an English cottage. Instead of windows there are glass doors opening on a large piazza. There is a large hall running through the house, with a fireplace in it. The hall is furnished like a room. There were some handsome vases upon the mantle, and a large porcelain dog with a large gilt padlock and a black chain around his neck. I like the house better than other houses that we see now. It is a very tasty house with an air of comfort and refinement about it, and such a beautiful cosy little parlor area. . . . Mrs. Farrar is a very friendly and entertaining lady. We had a very interesting conversation about the Battle of Bennington. Before coming to the South they resided in Bennington, Vermont.

Mr. Bridwell went to the manufactory and stayed with Mr. Farrar until dinner time, then both Mr. Farrar and himself returned to dinner. We had a very nice dinner and the best of cold water, better than ice water. After dinner, Mr. B. went to Bath on some business. He returned after a few hours.

Laura and myself gathered some acorns and we talked about many things. Then she went to the Church with me and I found a very neat comfortable church capable of holding 200 persons. There was a handsome Bible and Prayer Books made a present to the church by Mrs. Gardner and her sister, Mrs. Harison. . . . We returned back to the house. . . . I told Mrs. Farrar that I felt like it was hard to say goodbye. Mr. Bridwell said that we had better start. Before we left Mrs. Farrar had cake handed to us.

We called at the manufactory on our way home. Mr. Farrar gave me a pitcher with a shepherd boy with his crook and pipes with him. At his feet is lying two little lambs. On the other side of the pitcher is a country maid standing near a fence. I got a soap cup and a mug. We bade Mr. Farrar goodbye then started for dear old Augusta. . . . We got there by eight o'clock and all the home folks were glad to see me. (37)

Both the road traveled by Mrs. Bush and the church she visited with Laura Farrar can be clearly seen in the map illustrated in figure 1.

Mrs. Bush neglected to mention whether the pitcher she had been given was porcelain or whiteware. Very few shepherd and shepherdess water pitchers are known. A porcelain example in the collection of the Charleston Museum (fig. 10) could have been modeled by Josiah Jones while he was still at Greenpoint, because another pitcher in a private collection that has been examined resembles Boch porcelain, a bit greasy to the touch and slightly greenish in its translucency. The design, however, is in the English manner and almost eighteenth century in appearance, unlike anything else attributable to Cartlidge or the Bochs. In fact, one wonders whether such a naive, pastoral design would have been thought suitable or saleable in New York City. On the other hand, it may have appealed to the landed gentry of the antebellum South. Any example of the shepherd and shepherdess water pitcher should be considered as probably made by the Southern Porcelain Company.

|

10. Shepherd and shepherdess water pitcher, porcelain, probably made by the Southern Porcelain Company, c. 1856 - 1860. Collection of the Charleston Museum, Charleston, S. C., acc. 32.122.1 MRF S-21,233.

To the products mentioned above, it is only possible to add Edwin AtLee Barber's claim that "Rockingham pitchers and spittoons of ornate form were made in the early days." No other forms can be reasonably ascribed to the Southern Porcelain Company while managed by W. H. Farrar.

THE IMPACT OF THE CIVIL WAR ON THE

SOUTHERN PORCELAIN COMPANY

By 1860, less and less pottery was being made at the factory. War clouds were gathering, and workmen who were immigrants or had grown up in the North became uneasy as talk of secession and diatribes against the Union swirled around their heads. It was in South Carolina, after all, that the incident occurred — the firing on Fort Sumter on 9 January 1861 — that set the whole conflict in motion. Neither Josiah Jones nor Enoch Barber appears in the Edgefield Census of 1860; Jones had already left South Carolina for Trenton, New Jersey. (38) (See Appendix II.)

The onset of the Civil War had a devastating effect on potteries in both the North and the South as young men rushed to enlist in support of one side or the other. Former Bennington men, Albert Cushman and Jerome Seymour, both of whom were pressers, "joined the Southern army," and Seymour was killed at the Battle of Fair Oaks, Virginia, on 1 June 1862. (39)

W. H. Farrar may well have returned with his family to the North before the reorganization of the company in 1861, but precisely where he went is unclear. Ceramic historian John Spargo said he became "engaged in the pottery industry in Philadelphia," (40) but his name could not be found in the city directories of the late 1860s or early 1870s. Ceramic historian John Ramsay claimed that Farrar had previously worked in Jersey City, and indeed a W. H. Farrar was listed in the 1870 Federal Census for Jersey City, but he was a "Watch Factory Hand" newly arrived from England. (41)

From 1861 to 1864, the Southern Porcelain Manufacturing Company struggled to survive alongside a newly created pottery near Bath, South Carolina, known first as the Palmetto Fire Brick Works and afterwards as the Bath Fire Brick Works. (42) When the factory at Kaolin burned in 1864, Joseph Wheeler was probably the company president. (43)

POSTWAR PORCELAIN AND EARTHENWARE

PRODUCTION AT KAOLIN

More than a year later, with the war over, a new porcelain manufactory began to rise from the ashes of the old Farrar enterprise and two articles about the venture appeared in the Edgefield Advertiser. The first, entitled "A Mine of Wealth," dated 19 September 1866, was hardly more than a puff for the company. It listed the officers, "all of Augusta," as R. B. Bullock, president; J. E. Marshall, secretary; and G. Schaub, general superintendent, and noted that "the work of introduction and manufacture is only in its incipiency." The second, on 10 October, only three weeks later, raved about a kaolin tea set that had been presented by R. B. Bullock to General M. W. Gary. "Everybody knows who General Gary is," proclaimed the article, "but who is Mr. Bullock?"

Southerners would certainly have known that Martin Witherspoon Gary, born in Cokesbury, South Carolina, in 1831, had commanded the last troops to leave the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. Cutting his way out after Lee's surrender at Appomattox, Gary had helped escort Jefferson Davis and his cabinet south, the members having their last meeting at the home of General Gary's mother in Cokesbury." (44) Today, however, information is more easily found about Rufus Brown Bullock, who has been profiled in most encyclopedias of American biography.

Bullock was born in Bethlehem, Albany County, New York, on 28 March 1834 and graduated from Albion Academy in 1850. After exploring various pursuits, he was sent in 1859 and 1860 to organize the business of the Adams Express Company, in the South Atlantic states. He established a headquarters in Augusta, Georgia, formed the Southern Express Company, and became one of its managers. During the war, he continued this activity under the direction of the Confederate government, creating railroads and telegraph lines — which may help explain his interest in a company that made insulators. Bullock was associated with the organization of the First National Bank of Georgia and was elected president of the Macon and Augusta Railroad. In 1868 he was elected governor of the state of Georgia, after which, it must be assumed, he no longer concerned himself with the operation of the porcelain works at Kaolin. (45) But the tea set he presented to General Gary in 1866 was described as "durable in quality and very elegant in tint and beauty of finish. Unfortunately we have no hint as to whether it was porcelain or whiteware.

Also during this postwar period, according to Edwin AtLee Barber, "Cream-pots, pitchers, etc., in white ware and porcelain, with raised leaves and imitation of wicker or basket work, were made to some extent." While the reference to raised leaves suggests the design on the marked whiteware creamer shown in figure 7, which is attributed to the Farrar period, it is highly unlikely that a southern company would be using an American eagle as part of its mark on the heels of the Confederate surrender. Basketweave pitchers, however, were being made by other American potteries at that time. The account book of modeler Ralph Scragg, of East Liverpool, Ohio, indicates that in fall 1869, he delivered molds for five sizes of basketweave pitchers (fig. 11) to Frederick Dallas, who was making Parian ware in Cincinnati, Ohio.

|

11. Basketweave pattern syrup pitcher, Parian ware, of the type represented by the sherd in figure 12. This example, made by Frederick Dallas of Cincinnati, Ohio, c. 1869, is impressed "F. DALLAS" in the foot rim. HOA 5¾". Ceramics and Glass Collection, Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C., acc. 75.40. Photograph J. G. Stradling.

Among a group of whiteware shards picked off the ground at the Southern Porcelain Company site in 1991 by Edgefield potter Stephen Ferrell was a single example of porcelain (fig. 12), molded in a basketweave pattern. Its presence suggests that the company did produce sheer, translucent ceramics and did indeed make basketweave pitchers in the later period, as Barber claimed. Other sherds gathered were parts of common white ironstone tablewares, of the kind produced by many American potteries for restaurants and hotels.

|

12. Sherd from basketweave pitcher, porcelain, found at the site of the Southern Porcelain Company, probably made c. 1866 - 1870. HOA 3", WOA 2 5/16". Private collection. MRF 23,470.

Little can be learned about the factory's final years, but if Rockingham-glazed pottery marked "S. P. Co." was actually made by the Southern Porcelain Company, it had to have been after the war and before 1877, around which time the company was sold to McNamee & Company of New York, a firm concerned with marketing clays rather than the making of pottery or porcelain. (46)

Following the war, northern as well as southern potteries took a while to resume production. Many young potters had been killed. New designs were slow to come onto the market, and for some reason American potters, unlike American glassmakers, were reluctant to make use of design patents. Consequently, Edwin Bennett's Rebekah at the Well teapot, created in Baltimore in 1851, was copied by countless companies and became one of the most popular pieces of American pottery ever made. (47) Rebekah teapots are found with both the plain "S. P. Co =" mark and the fancier mark including the word "FIREPROOF."

Joseph Mayer's Arsenal Pottery, founded in Trenton, New Jersey, in 1876, (48) produced both an anchor pitcher and a Rebekah at the Well teapot (fig. 13). The teapot is marked on the bottom "FIREPROOF / J. MAYER / TRENTON" (fig. 13a). (49) Fireproof ware, for use in or on top or the stove, had been advertised as early as 1833, but the practice of impressing the word itself into the bottoms of kitchen crockery did not take place until much later. (50) The word may have first appeared on English Rockingham and yellow ware, especially articles from Derbyshire, but the earliest use of "FIREPROOF" in an American mark was by J. E. Jeffords & Company of Philadelphia in association with a patent awarded to Nathaniel Plympton of Boston on 28 June 1870. When teapots were placed on top of a cast iron stove, they tended to crack as the bottom rim came into contact with the extremely hot surface. To eliminate this problem, Plympton devised "as new or improved manufacture, an earthenware tea-pot, having its bottom notched or grooved. (51)

|

13. Rockingham-glazed Rebekah at the Well teapot, made at the Arsenal Pottery, 1876 - 1879. HOA 7¾". Collection of the Newark Museum, Newark, N. J., acc. 48.442. Photograph the Newark Museum / Art Resource, New York.

|

13a. Impressed mark on the underside of fig. 13, "FIREPROOF / J. MAYER / TRENTON." Photograph the Newark Museum / Art Resource, New York.

John E. Jeffords, who had obviously received a license to utilize the Plympton patent, was making Rebekah at the Well teapots with notched foot rings by 1874. (52) He also made Rockingham-glazed kitchen wares with raised pads on the bottoms, which was another way of approaching the problem. A Jeffords ad in the Crockery and Glass Journal of 27 April 1876 illustrates a "Basket Pattern" teapot. Also shown are Chinese and medallion teapots, both of which have "S. P. Co =" -marked counterparts. Since all of the teapots impressed "S. P. Co." have either raised pads or notched bottoms, none could have been made before the 1870s, which calls into serious question whether any could have been produced at Kaolin, South Carolina.

Looking back to discover how "S. P. Co." marked earthenwares ever came to be attributed to the Southern Porcelain Company, one finds that the earliest connection may have been made by Edwin AtLee Barber's widow or by Freeman's Auction Gallery in Philadelphia, when putting together the catalogue for Barber's estate sale, a year after his death in December 1916. (53)

Lot 339 in the catalogue was a pitcher, 10½ inches in height. "Brown and Yellow Glaze, Raised Figures of Anchor on Each Side, Rope around Edge, &c. Marked 'S. P. Co.' (Southern Porcelain Co.), Kaolin, S. C." So far as can be found, no such attribution was made by Barber himself in any of his books or articles.

The questionable judgment, however, was accepted and repeated by others. In 1947, C. Jordan Thorn's Handbook of Pottery and Porcelain Marks was issued by the Tudor Publishing Company of New York City. It contained the plain "S. P. Co =" mark attributed to the "Southern Porcelain Co., Kaolin, S. C. 1856 - 64." (54) In 1957, the Henry Ford Museum acquired a Rebekah at the Well teapot in a "green and brown glaze" with an "S. P. Co. / FIREPROOF" mark, and a brown-glazed anchor pitcher with the "S. P. Co =" mark from the collection of the late George S. McKearin. (55) There is also in the museum a medallion teapot with the latter mark. All three objects were originally attributed to the Southern Porcelain Company.

Someone, in the years that followed the Barber estate sale, should have wondered at the number of brown pottery pieces marked "S. P. Co." in museums and private collections, especially in the North. It should have seemed at least a little bit strange that so many examples had survived a nineteenth-century manufactory in rural South Carolina. But then, if the Southern Porcelain Company did not make the group of objects marked "S. P. Co.," with or without the word "FIREPROOF," who did?

A convincing answer is found in an article from the 9 December 1875 issue of the Crockery and Glass Journal on the Speeler Pottery Company of Trenton, New Jersey. Henry Speeler and James Taylor had come from East Liverpool, Ohio, to Trenton, New Jersey, in 1852. In 1860 they parted company; the former established the Henry Speeler pottery and later the Henry Speeler & Sons pottery. Following Henry Speeler's death in 1871, his sons reorganized under the name "Speeler Pottery Company" (fig. 14). (56)

|

14. Speeler Pottery Company advertisement, listing "Fire-Proof Ware," from Boyd's Trenton Directory, Trenton, N. J., 1873.

The Crockery and Glass Journal article reported that the company had "the largest kilns in operation in the world" and employed "from ninety to one hundred hands." It added, "In teapots alone they have the 'Rebecca,' 'Chinese,' 'Medallion,' 'Pine-Apple,' and 'Vine,' all in new shapes."

The fact that teapots in two of these designs were advertised several months later by Jeffords, as has previously been mentioned, was more than a coincidence. The officers of the Speeler Pottery Company, as listed in Boyd's Trenton Directory of 1873, were Alex Morrison, president; William F. Speeler, vice-president; William Hunt, treasurer; H. A. Speeler, superintendent; and Jno. E. Jeffords, secretary.

It is highly unlikely that the same "new" shapes being offered by the Speeler and Jeffords potteries in late 1875 and 1876 were also being made by the Southern Porcelain Company a year before it was sold. In fact there is no evidence, archaeological or otherwise, that any Rockingham-glazed earthenware was being made by the South Carolina company in the 1870s. On the other hand, Rockingham wares were featured by both the Jeffords and Speeler firms in their exhibits at the Philadelphia Centennial Fair in 1876. Speaking of the teapots in the Speeler display, a Crockery and Glass Journal reporter noted, "That with 'Rebecca at the Well' is especially neat." (57)

The strongest argument against the manufacture of Rebekah teapots by the Southern Porcelain Company, has come with the recent discovery of two biscuit examples (fig. 15) impressed with each version of the "S. P. Co." mark. (fig. 15a) Found in an antiques shop in Englewood, New Jersey, the larger is 7¾ inches high and the smaller, 6⅞ inches. Since neither are glazed, they are unusable — not the sort of thing Mrs. Porcher, Mrs. Willis, or Mrs. Bush would have wanted to bring home from the factory at Kaolin. Biscuit pieces of pottery are not looked upon as great treasures by the general public and seldom travel far from their place of origin.

|

15. Pair of biscuit Rebekah at the Well teapots produced by the Speeler Pottery Company of Trenton, N. J., with impressed "S. P. Co." mark on the underside. Private collection; photograph Richard P. Goodbody.

|

15a. Marks on the teapots in fig. 15. Photograph Richard P. Goodbody.

|

15b. Mold details on the teapots in fig. 15. Photograph Richard P. Goodbody.

Any possibility that the fancier "FIREPROOF" mark might have appeared on Rebekah teapots made by the Southern Porcelain Company, while the simpler sans-serif mark was employed by the Speeler firm, is dispelled by an examination of the wares themselves. Both teapots were fashioned distinctively, in direct imitation of the Bennett original, indicating that the molds for both were created by the same hand. The lines of each two-piece mold run vertically to the sides of the spout and handle instead of beneath them as is usually the case. (fig. 15b) It requires a powerful imagination to think that either of these two teapots came to Englewood from South Carolina rather than from nearby Trenton, New Jersey.

The conclusion must therefore be faced that brown earthenware pitchers and teapots found with either the fancy or plain "S. P. Co." marks were made by the Speeler Pottery Company of Trenton, New Jersey, between 1871 and 1879 before the pottery was sold to James Carr of New York City.

This leaves to be considered only the numerous porcelain and ironstone tablewares stamped with various marks incorporating the letters "S. P. Co." Generally, the shapes of these objects do not conform to any that were fashionable prior to 1877; the marks are therefore more likely to be those of later firms such as the Steubenville Pottery or the Sebring Pottery Company of Ohio.

A final word of caution to anyone encountering a piece of earthenware marked "S. C. P. Co." (fig. 16). This is the mark of the South Carolina Pottery Company, which was in operation during the 1880s near Miles Mill, some seven miles to the north of Kaolin. To date, no intact specimen from this pottery has been reported.

What remains, then, that can be reasonably attributed to the Southern Porcelain Company? Without question: a creamer with leaves in relief (fig. 6), a basketweave sherd (fig. 12), and some marked insulators. Probably: certain porcelain corn pitchers, a Parian sheaf of wheat syrup pitcher, a porcelain shepherd and shepherdess pitcher, and any basketweave pitcher matching the aforementioned sherd.

|

16. Sherd of a vessel made by the South Carolina Pottery Company, c. 1880, marked "S. C. P. Co." Private collection; photograph Carl Steen.

On the basis of the above reassessment, it becomes obvious that most of the products of the Southern Porcelain Company were never marked. While previously unidentified examples of the factory's pottery and porcelain may yet come to light, it is advisable for collectors to follow a simple rule of thumb: If it is marked "S. P. Co." without "Kaolin, S. C.," it was not made by the Southern Porcelain Company.

J. GARRISON STRADLING, a graduate and former assistant professor of journalism at the University of Georgia, is currently a ceramics historian and antiques dealer in New York City.

APPENDIX I.

THREE W. H. FARRARS AND THEIR ANCESTORS.

|

APPENDIX II.

INFORMATION PERTAINING TO WORKERS AT THE

SOUTHERN PORCELAIN COMPANY.

Some additional information can be learned about the Southern Porcelain Company from occasional references to one or more of the men who worked there and from 1860 census statistics for those who were probably associated with the company (see below). Many of the workers lived in boarding houses, of which there were three near the factory, run respectively by Betsy Pond, Mrs. C. Cassle, and Stephen Keiser and his wife. The only other industry in the area at the time was the Bath Paper Mill, but it is difficult to be certain who worked where, when dealing with a listing of dwellings and their inhabitants.

In addition to the list of names, spelled here as they were written by hand on the pages of the Census, a few more facts can be added about the factory workers. James Kenny had come south from Vermont, where his daughter had been born more than six years previously. A notice of Kenny's death in the Augusta Daily Chronicle and Sentinel of 16 November 1866, said he had at one time been a salesman in the ware room of the Southern Porcelain Company.

Among the men who had worked for the United States Pottery Company before coming to South Carolina was William McLee, an English jigger man. He may well have been the same William McLee who joined forces with George Wolfe to open a pottery in Peoria, Illinois, in the early 1860s. (58) Silas R. Wilcox, a maker of Parian ware, arrived in December 1858 and departed in July 1860.

Factory Workers in Bath, South Carolina, listed in the 1860

United States Census for the Edgefield District.

|

NOTES.

1. The history of the Rebekah at the Well teapot, as well as the rationale for the archaic spelling of "Rebekah" is discussed in J. G. Stradling, "Puzzling Aspects of the Most Popular Piece of Pottery Ever Made," The Magazine ANTIQUES, February 1997, 334 - 335.

2. The history of the Southern Porcelain Company cited here is from Edwin AtLee Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, 3d ed., and Marks of American Potters (reprint, New York: Feingold & Lewis, 1976). The third edition of The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States was originally published in New York by G. P. Putnam in 1909. ~~Marks of American Potters was originally published in Philadelphia by Patterson & White in 1904; in addition to the reprint cited above, it was reprinted separately by Cracker Barrel Press of Southhampton, N. Y. (c. 19710, and by Ars Ceramics of Ann Arbor, Michigan (1976).

3. Ibid., 187 - 188.

4. Ibid., 188.

5. Ledgers of the Bath Fire Brick Works, in the South Carolina Library at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, indicate that on 27 April 1864, the Southern Porcelain Company settled a bill with that firm for $1,750.

6. The account was reprinted on 19 October 1864 in the Edgefield (South Carolina) Advertiser.

7. Mary E. Davison, "William H. Farrar, Potter," The Magazine ANTIQUES, March 1939, 122 - 123.

8. Information on the Farrar family was drawn from three major sources: (Timothy Farrar, 1788 - 1874), Memoir of the Farrar Family, by a Member of the New England Historical Genealogical Society (Boston, 1853), 12, 37, 38, 43; Lara Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1950), 113, 139, 148; Elizabeth Collard, Nineteenth-Century Pottery and Porcelain in Canada (Montreal: McGill University Press, 1967), 271.

9. Memoir of the Farrar Family, 38, 43.

10. William H. Farrar vs. Christopher W. Fenton & the United States Pottery Co., Bill and Cross Bills filed in the Bennington County Court of Chancery, December 1857 to December 1860 and Decree of June 1865. Vermont State Archives, Montpelier. Henceforth cited as Farrar vs. Fenton & the U. S. Pottery Co. My thanks to Warren F. Broderick and Catherine Zusy for providing copies of this material.

11. An article in Gleason's Pictorial Drawing Room Companion, Boston, 22 October 1853, 261.

12. Bennington Banner, 13 March 1873; notebooks of Dr. Burton N. Gates, who interviewed surviving workers from the Bennington Pottery in 1914 and 1915, in the Bennington Museum Collection, Bennington, Vermont (courtesy of Catherine Zusy).

13. Deed Book 33, Town Clerk's Office, Bennington, Vermont, 522 - 524.

14. Farrar vs. Fenton & the U. S. Pottery Co.

15. Bradford L. Rauschenberg, "Andrew Duche: A Potter 'a Little Too Much Addicted to Politicks,'" Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, XVII, I (May 1991), 30, 56 - 57. For more information about the history of ceramics and the search for kaolin clays in South Carolina, see other articles by Rauschenberg in the Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, XVII, 1 and 2 (May and November 1991).

16. Farrar vs. Fenton & the U. S. Pottery Co.

17. This, the two paragraphs above, and other paragraphs below concerning legal actions were taken from Farrar vs. Fenton & the U. S. Pottery Co.

18. The Potters and Potteries of Bennington, by John Spargo, (New York: Antiques, Inc., 1926; reprint, the Cracker Barrel Press, n.d.), 133 - 134, 142.

19. Notebooks of Dr. Burton N. Gates, quoting Dr. Silas R. Wilcox.

20. Floyd R. Mansberger with Eva Dodge Mounce, The Potteries of Peoria, Illinois, Historic Illinois Potteries Circular Series, II, I (Springfield, Ill.: Foundation for Historic Research of Illinois Potteries, 1990), 2 - 6.

21. Farrar vs. Fenton & the U. S. Pottery Co.

22. Spargo, ~~The Potters and Potteries of Bennington, 153.

23. Farrar vs. Fenton & the U. S. Pottery Co.

24. Notebooks of Dr. Burton N. Gates, quoting Dr. Silas R. Wilcox.

25. Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, 175; The Brooklyn City Directory & Greenpoint Bushwick Directory, 1854.

26. See Richard Carter Barret, Bennington Pottery and Porcelain (New York: Bonanza Books, 1958), p. 122, pl. 173.

27. Personal communication, Larry Veneziano, Chicago, Ill., 1996.

28. The insulator was illustrated in an article by Edward Wenham, "Early Hard-Paste China of Carolina," ~~The Fine Arts (August 1933), 31. 29. Edwin AtLee Barber, Marks of American Potters, 155.

30. Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, 189, fig. 79. For Champion's work with South Carolina clay, see Bradford, L. Rauschenberg, "A Clay White as Lime," Journal of Early Southern Decorating Arts, XVII, 2 (1991), 68 - 69, and Walter E. Minchinton, "Richard Champion, Nicholas Pocock, and the Carolina Trade," South Carolina Historical Magazine, 65, 2 (April 1964), 87 - 97.

31. Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, 188, fig. 78.

32. ~~Ibid., 451.

33. See Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, American Porcelain 1770 - 1920 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art/Abrams, 1989), 111, 112, 116 and illustrations on page 110 and 117. The Bochs did not begin making porcelain in Greenpoint, however, until the early 1850s rather than 1844. Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States,162.

34. Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village, Dearborn, Michigan, acc. No. 61.72.13. My thanks to Arthur F. Goldberg for reminding me about this pitcher.

35. A Ceres syrup pitcher in gray-green stoneware is illustrated in Kathy Hughes, ~~A Collector's Guide to Nineteenth-Century Jugs, II (Dallas, Tex.: Taylor Publishing Co., 1991). The handle is plain instead of twiggy, and the wheat ears do not reach as high as on the Parian syrup pitcher. My thanks to Jay A. Lewis for bringing this source to my attention.

36. Barret, Bennington Pottery and Porcelain.

37. Transcription provided by a descendant of Mrs. Bush (courtesy Stephen Ferrell).

38. United States Census for the First Ward, Trenton, N. J., 1870, p. 297. Jones was 69 years old and his wife Mary was 68.

39. Notebooks of Dr. Burton N. Gates, quoting Henry W. Marsh and Dr. Silas R. Wilcox.

40. John Spargo, "The Facts About Bennington Pottery, II: The Works of Christopher Weber Fenton," The Magazine ANTIQUES, May 1924, 237.

41. John Ramsay, American Potters and Pottery (New York: Tudor Publishing Co., 1947), 88.

42. According to Edwin AtLee Barber, in spring 1862 Colonel Thomas J. Davies, a cotton planter, was induced by Anson Peeler, who had been working in South Carolina for some eight years, to embark on the manufacture of firebrick near Bath, on the South Carolina railroad. Peeler was put in charge of the company, which, at first was called the Palmetto Fire Brick Works, then the Bath Fire Brick Works (Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, 248 - 250 and 465 - 467). The company employed slaves, as is evidenced in its ledgers by payments to their various masters. Colonel Davies informed Barber that during the first year, the Negroes used their spare time to make homely designs in course pottery, such as face jugs of the sort that would later make the Edgefield District famous among collectors of folk pottery.

Barber says that in 1863 a great demand sprang up for earthenware jars, pitchers, cups, and saucers — and the firebrick works was partially transformed to meet the need. Confederate hospitals were supplied with thousands of these articles of rude and primitive shape, the ware being composed of three-fourths to five-sixths parts of kaolin with alluvium earth from the swamp lands of the Savannah River. This composition made a tough body which partially vitrified in burning. With sand and ashes mixed thoroughly as a glaze, excellent results were obtained. The ware was black or brown, clumsy, and entirely devoid of ornamentation.

In the summer of 1864, operations at the pottery were suspended. On August 28, the Fire Brick Works made its final payment of "Confederate States tax." On January 1st, 1865, as General Sherman was turning his attention toward South Carolina, following the Union Army's fiery march from Atlanta to the sea, the company's accounts were settled among the principals and the pottery passed into history. (Ledgers of the Bath Fire Brick Works, Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

43. Wheeler's obituary in the 3 April 1866 Augusta Daily Chronicle and Sentinel stated that he was "many years ago President of the Merchants and Planters Bank" but "more recently President of the Southern Porcelain Company."

44. Ezra J. Warner, Generals in Grey, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959), 102.

45. Appleton's Cyclopaedia of American Biography, (New York: d. Appleton & Co., 1887), I, 447.

46. Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States, 191.

47. Eugenia Calvert Holland, Edwin Bennett and the Products of His Baltimore Pottery (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1973), 12, 13.

48. Major E. M. Woodward and John F. Hageman, History of Huntington and Mercer Counties, New Jersey (Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1883), 693.

49. The teapot cited was acquitted in 1915 by the Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey. An example of a Mayer anchor pitcher is in the collection of the New Jersey State Museum, Trenton. 50. "Fire Proof Earthenware" was advertised by Day, Venables & Taylor of Norwalk, Connecticut, on 26 November 1833 in the Norwalk Gazette. See Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares, 201. 51. Document filed under United States Patent No. 164,764.

52. Trade catalogue, Pennsylvania Historical Society, Philadelphia (courtesy Jane Perkins Claney).

53. Sale dates, Monday and Tuesday, December 10 - 11, 1917.

54. Barber's Marks of American Potters, originally published in 1904, was out of print by the 1940s and rarely found in libraries. Until the book was reprinted around 1971 by Cracker Barrel Press in Southhampton, New York, many collectors relied on the United States section of Thorn's book.

55. Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village, Dearborn, Michigan, acc. 7.64.23 a and b. My thanks to Arthur F. Goldberg for this information.

56. Woodward and Hageman, History of Huntington and Mercer Counties, New Jersey, 689; Barber, Marks of American Potters~~, 77.

57. Crockery and Glass Journal, probably vol. 3, no. 24 or 25 (June 1876), p. 18. The issues originally consulted were lost more than twenty years ago by the New York Public Library and presumably destroyed.

58. Mansberger and Mounce, The Potteries of Peoria, Illinois, 2.

As well as the persons noted above and in the photo captions, thanks are due to Bradford L. Rauschenberg of MESDA for insisting that the author tackle this subject, to the author's long-suffering wife Diana, to George R. Hamell, Susan H. Myers, Carl Steen, and to everyone who contributed over the years to the file on the Southern Porcelain Company at the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA)