[Trade Journal]

Publication: The Electrical Engineer

New York, NY, United States

vol. 17, no. 316, p. 445-447, col. 1-2

THE JUBILEE OF THE AMERICAN TELEGRAPH.

|

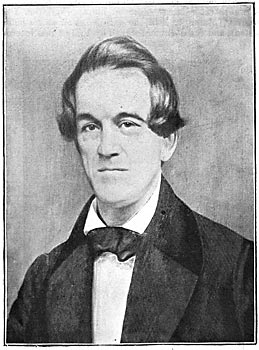

| Prof. S. F. B. Morse |

THE fact that this year, and this week, witness the jubilee of the telegraph in America, has served to fill the newspapers with reminiscences and to revive the story of the first messages, in a hundred different forms. It has been stated, not for the first time, that the "first message," was one sent on May 1, in a casual way, announcing the national nominations of Clay and Frelinghuysen, but the writer has in his possession a memorandum in Morse's own handwriting of a similar message as to the nomination of Governor Pratt, sent April 30. Be this as it may, the accompanying fac-simile shows that Morse himself regarded May 24, 1844, as the day, and that it was then that the historic message, "What hath God wrought ?" was sent by Miss Annie G. Ellsworth, who had been the bearer to Morse of the news in 1843 in Washington,that Congress had appropriated $30,000 for tests of the telegraph. Miss Ells worth,the daughter of the Commissioner of Patents, a personal friend of Morse, is now the widow of Roswell Smith, late president of the Century Magazine. The promise that Morse made to her as a reward for her good news, was carried out on May 24, 1844. The experimental line between Washington and Baltimore had been finished; Morse had set up his instrument in the Supreme Court at Washington, while Alfred Vail had the other one at the Mount Clare depot in Baltimore. Miss Ellsworth now gave Morse the message, suggested by her mother, and that wonderfully apt sentence was transmitted in triplicate to Baltimore. It was the first message ever sent by a recording telegraph. A part of the message, with Prof. Morse's endorsement is here shown, in fac-simile, from the original as preserved by Mrs. Roswell Smith; and a duplicate is in the possession of the State Historical Society at Hartford, Conn.

|

| Fac-Simile of First Message, Now in Possession of Mrs. Roswell Smith. |

| |||

| Alfred Vail. (From A Portrait in the Possession of the Vail Family.) |

Such an occasion as the present is appropriate for rendering credit to those who were the pioneers with Morse in this first great field of electrical engineering. THE ELECTRICAL ENGINEER has just concluded a series of articles by Miss Mary Henry, daughter of Prof. Henry, relating her father's work in this direction, and her filial tribute has left nothing for anyone else to add, so fully, so gracefully and so earnestly has her story been told. Morse's great place in history is well established, and no repetition of the history of his struggles and successes can make his fame greater. We venture, however, to place with these worthies of the past, Alfred Vail, whose work has but too often been overlooked, so that the reaction of the sense of justice has even threatened to do him injury by an unduly enthusiastic attribution to him of pretty well everything that was done in the early days. The probability is that if Morse had not found Vail, he would have hit upon somebody else, but it was providential that these two great men, so admirably supplementing each other, should have come together, the imagination and intuition of the leader, calling out the practical skill and genius of his assistant at every step of the work. As our readers are well aware, much of the experimental work with the crude telegraph was done at Speedwell, N. J., the home of Vail's father, who supplied funds for the enterprise, and whose iron works are here shown from an old letterhead of 1847. A few weeks after Morse obtained his appropriation from Congress (March 4, 1843) he enrolled Vail as his official assistant, and the document signed by Vail on that interesting occasion is here reproduced. It should be mentioned, however, that a contract already existed between them, dated Sept. 23, 1837, as to the financial devision of the rights in the invention, giving Vail, among other things, one-quarter in this country, which was afterwards changed to three sixteenths. This document is also in the possession of the writer, but is too voluminious and verbose for reproduction here, filling as it does several sheets of manuscript.

|

| The Speedwell Iron Works. (From An Old Letterhead, Dated 1847.) |

| |||

| Annie G. Ellsworth, Now Mrs. Roswell Smith. (From An Ivory Miniature Painted About 1844, by Freeman.) |

Vail began his new duties very promptly, as numerous letters between himself and Prof. Morse testify. We give here the text of Prof. Morse's instructions to him for the little sensational feat of sending the political news on May 1, 1844:

Mr. Vail, at Annapolis Junction.

Get everything ready in the morning, for the day, and do not be out of hearing of your bell. When you learn the name of the Vice Prest. nominated, see if you cannot give it to me, and receive from me an acknowledgment of its receipt before the cars leave you. If you can it will do more to excite the wonder of those in the cars, than the mere announcement that the news is gone on to Washington. When the cars are in sight from Baltimore, which will be about 10 a. m. and 5 p. m., prepare me for the announcement ; by the letter after the usual beginning and ending. When they arrive at your station, get the name of Vice Prest. If Mr. Evans, write simply - - - - — - — — - - - - ; or Mr. Davis, write --- - - - — - - - — - - - - - , and I will acknowledge by - - - - , which means "very well" as well as "yes." Afterwards you can repeat the name and any other information you may have received, but the name of Vice Prest. is of most importance. There will be hours when it is of more importance to be attentive at the Register than at other times. At 10 a. m. until 12 m., from 1 to 3 and from 5 p. m. until 6 or 6 1/2. It may be well to have an evening trial on some dark and perhaps foggy night, to show the independence of the Telegraph on the weather. At 12 m. disconnect so that Mr. Cornell may test the wires to the point where he is at work, and continue disconnected 1 hour. Tell Mr. Cornell this. Do not forget to keep your circuit closed after writing.

|

| Vail's Contract As Assistant Superintendent to Morse. (Reduced From the Original in the Possession of T. C. Martin.) |

|

| Henry L. Ellsworth, First U. S. Commissioner of Patents. (From An Old Daguerreotype.) |

On June 14, 1844, Vail, in Baltimore, writes to Morse in Washington: "How beautiful everything worked yesterday! You have furnished a long list of the proceedings of Congress. Will you cut one of the accounts out and put it up in the Rotunda? It may have a good effect. I was visited by hundreds yesterday, and the curiosity is unabated."

It is a familiar fact that the wires between Washington and Baltimore were first to have been laid underground, and that Ezra Cornell did some very interesting but unsuccessful work in this direction for Morse, even inventing a plow to cut the trench for the reception of the cable. Hut when the cable was laid from Baltimore to the Relay House, seven miles distant, the leakage was so great that, to Morse's distress, it was found necessary to abandon the plan. He then, by permission of a letter from the U. S. Treasury, dated Feb. 5, 1844, tested the plan "of suspending the conductors on posts above ground," along the Baltimore railroad. For this purpose two No. 14 copper wires, covered with cotton saturated with gum shellac, were strung, held at the poles between two plates of glass. The pole plan had been described by Morse in a letter to the Treasury as early as 1837, as the cheapest, so that the "irrepressible conflict" between the overhead wires and subways began even at that primeval date. The insulating plan now adopted was devised by Mr. Cornell, although it was not long before the bureau knob pattern of insulator was resorted to as far superior to the glass plates with the wooden cover nailed over them.

|

| Prof. Morse's Diagram of the Washington-Baltimore Line. (From Original in Possession of T. C. Martin.) |

Prof. Morse's personal vigilance and superintendence are evident at every turn. A sheet in his fine penmanship now lies before the writer, who has reproduced from it the little sketches shown herewith. The sheet is dated June 26, 1844, and deals with the questions of repairs on aerial lines, Prof. Morse says:

|

| Prof. Morse's Sketches of Line Repair Material, June, 1844. (From Original in Possession of T. C. Martin.) |

Let Cleveland prepare a rope ladder and make some experiments of repair, by putting oak pins in the tops of a few of the posts, thus: the pins may be 16 inches long and an inch in diameter. The articles wanted for repair ordinarily will be, the rope ladder (1), a light pole (2) 20 feet long with an iron cross at top, a coil of wire (3) of 160 feet in length, a spirit lamp (4), a stick of tin for solder (5), a bottle of chloride of zinc (6), a pair of cutting calipers (7), a bottle of alcohol (8), and matches (9); all but 1 and 2 in a small basket.

|

| Prof. Morse's Sketches of Line Repair Material, June, 1844. (From Original in Possession of T. C. Martin.) |

Prof. Morse also deals with the problem of temporary repairs in a careful but naive manner. He says:

Very little interruption would take place if the train that discovered a break would stop not more than 5 minutes, and being furnished with pieces of wire already prepared for the purpose, anyone could simply unwrap and scrape the broken ends, and unite them by twisting the ends of the pieces of wire to them; and then give notice of the place to the inspector at either terminus, that a more permanent repair may be made. If this is done, so that the wire afterwards does not touch the ground, the communication will be established, and the process of more permanent repair will not break it again.

|

| Prof. Morse's Plan of Repairing Line Along Railroads. (From Original in Possession of T. C. Martin.) |

We do not now expect passengers to jump off a train and make telegraph repairs while the train waits, but these little touches are quaint and show us how long it takes to get the details of a great new art in their proper relation to other things and in their proper perspective of value and importance. Humble and weak as these beginnings were, it is by just such stages and by just such effort all the way, that the great modern telegraph system has been created and perfected.

One pathetic note comes in through all the celebrations of the current week, in the fact that the work of demolition has just begun at the old University of the City of New York, where Morse made his first experiments. The farewell exercises took place May 18. But through the laboratory that saw Morse's first wires strung has gone, his memory lives on forever.