[Trade Journal]

Publication: Verbatim Record of the Proceedings of the Temporary National Economic Committee

Washington , DC, United States

vol. 1, no. 9, p. 253-276, col. 1-3

VERBATIM RECORD

of the

Proceedings of the

TEMPORARY NATIONAL

ECONOMIC COMMITTEE

VOLUME 1

December 1, 1938 to January 20, 1939

CONTAINING

Economic Prologue

Automobile Patent Hearings

Glass Container Patent Hearings

Presentation on Patents by Department of Commerce

Published 1939 by

THE BUREAU OF NATIONAL AFFAIRS, INC.

WASHINGTON, D. C.

·

·

Eighth Day's Session

_____________________

VERBATIM RECORD

of the Proceedings of the

Temporary National Economic Committee

Vol. 1, No. 9 WASHINGTON, D. C. Dec. 14, 1938

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 14, 1938.

THE TEMPORARY NATIONAL ECONOMIC COMMITTEE MET AT 10:45 A. M. PURSUANT TO ADJOURNMENT ON TUESDAY, DECEMBER 13, 1938, IN THE OLD CAUCUS ROOM, SENATE OFFICE BUILDING, SENATOR JOSEPH C. O'MAHONEY PRESIDING.

PRESENT: SENATOR O'MAHONEY OF WYOMING, CHAIRMAN; SENATOR WILLIAM E. BORAH OF IDAHO; SENATOR WILLIAM H. KING OF UTAH.

REPRESENTATIVE HATTON W. SUMNERS OF TEXAS, VICE-CHAIRMAN OF THE COMMITTEE; REPRESENTATIVE B. CARROLL REECEOF TENNESSEE.

MR. THURMAN W. ARNOLD, ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL, REPRESENTING THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE; WENDELL BERGE, SPECIAL ASSISTANT TO THE ATTORNEY GENERAL.

MR. RICHARD C. PATTERSON, JR., ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF COMMERCE, REPRESENTING THE DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE.

MR. HERMAN OLIPHANT, GENERAL COUNSEL, REPRESENTING THE TREASURY DEPARTMENT; ADMIRAL CHRISTIAN JOY PEOPLES, DIRECTOR OF PROCUREMENT.

MR. LEON HENDERSON, EXECUTIVE SECRETARY OF THE COMMITTEE.

COUNSEL: H. B. COX (CHIEF COUNSEL); GEORGE W. WILLIAMS, JOSEPH BORKIN, ERNEST MEYERS, BENEDICT COTTONE, CHARLES L. TERREL, VICTOR H. KRAMER, J. M. HENDERSON AND SEYMOUR LEWIS.

ALSO PRESENT: DR . WILLARD THORP

The CHAIRMAN. The Committee will please come to order.

Mr. Cox, are you ready to proceed? Is Mr. Levis to be on the stand again this morning?

Mr. COX. Yes. Mr. Levis will take the stand.

The CHAIRMAN. Have you brought an additional witness?

Mr. COX. This is Mr. Williams, counsel for the company. I think we might have him sworn; he may not testify.

The CHAIRMAN. Mr. Williams, do you solemly [sic] solemnly swear that the evidence you are about to give in this proceeding will be the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth so help you God?

Mr. WILLIAMS. I do.

Mr. COX. Just give the reporter your name and address.

Mr. WILLIAMS. Lloyd T. Williams, 2025 Parkwood Avenue, Toledo, O.

Mr. COX. You are counsel for the Owens-Illinois?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Counsel for the Owens-Illinois Glass Company.

TESTIMONY OF WILLIAM E.

LEVIS, PRESIDENT, OWENS-

ILLINOIS GLASS COMPANY,

TOLEDO, O., (Resumed.)

AND

LLOYD T. WILLIAMS , COUNSEL

OF OWENS-ILLINOIS

GLASS COMPANY, TOLEDO,

OHIO.

Mr. COX. Mr. Levis, there are one or two loose ends in yesterday's examination that I would like to go over before we go ahead. Yesterday when I was asking you about your directorships held in other companies, I neglected to ask you whether you were a director of the Lynch Company.

Mr. LEVIS. No, sir.

Mr. COX. You never were a director?

Mr. LEVIS. No. sir.

Mr. COX. I also think it might be useful if you would tell me whether in speaking of the group of persons we described yesterday as the Levis group you included Mr. Boeschenstein.

Mr. LEVIS. I would have included him.

Mr. COX. Yesterday you told us you were a director of the National Distillers and of the Gilbey Company. Do you recall that?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir.

Mr. COX. Both of those companies use bottles in their business?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir.

Mr. COX. Do they buy bottles from Owens-Illinois?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir.

LEVIS GROUP HOLDINGS

Mr. COX. I think I also neglected to ask you what percentage of the total outstanding stock of Hazel-Atlas is owned by what we describe as the Levis group. Can you give me a figure on that?

Mr. LEVIS. The Illinois Glass Company owned, I think, a maximum of 22,000 shares. I may be wrong in that. It may have gone as high as 25,000, but for the longest period of time the holding was 20,000 shares, and that was the amount we distributed in liquidation.

Mr. COX. In the case, of the Lynch Corporation, will you tell us how many shares in that the Levis group held?

Mr. LEVIS. There was distributed in kind at the time of liquidation 4,500 shares.

Mr. COX. I have a figure here which we obtained from your company of about 6,000. I wonder if we could some timework out that discrepancy. That is a figure as of today, based on the holdings of members of the Levis group.

Mr. LEVIS. That probably is so. The Illinois Glass Company was a stock holder of record of 4,500 shares , and I own some shares personally, which together, maybe, with the holding, might be 6,000 shares.

Mr. COX. I am willing to check that.

Mr. LEVIS. I am willing that it stands as 6,000.

Mr. COX. The exact figure I have is 6,644 shares.

Mr. LEVIS. That is probably correct.

PATENT LICENSES

Mr. COX. Mr. Levis, I'd like to ask you some questions about the testimony which you gave me in respect to the company's attitude towards taking licenses on patents. As I understood, your testimony yesterday was that the attitude, or your own atitude [sic] attitude and that of the Illinois Glass Company was that all licensees of Hartford-Empire should be treated in the same way. Is that correct?

Mr. LEVIS. Would you make that a little clearer, Mr. Cox?

Mr. COX. Well, I will put the question this way: It is your attitude and the attitude of the Illinois Glass Company that no licensee of Hartford-Empire should receive preferential treatment over another licensee.

Mr. LEVIS. We weren't concerned with anybody else's business, Mr. Cox. As far as we were concerned, we had always made bottles of every description and we weren't going to sit back and be throttled by any licensing policy on the part of either Owens or Hartford. We went out until we got enough devices licensed to make everything that we had always made. What the other fellow did, that was his business.

Mr. COX. You then were not interested in whether you got the same treatment from Hartford-Empire as a licensee that the other licensees got?

Mr. LEVIS. No, we had a favored nation clause, that is, no one could have anything more favorable that we could have.

Mr. COX. And that was your attitude on that question?

Mr. LEVIS. It was the attitude on that or even the purchase of supplies.

Mr. COX. Was that the attitude of the Owens-Illinois Company after you became connected with that and acquired the assets of the Illinois Glass Company?

Mr. LEVIS. Well, as I said yesterday, to restate, I inherited a situation in Owens-Illinois which I didn't know very much about.

Mr. COX. The thing you speak of inheriting I presume is the 1924 contract.

Mr. LEVIS. Well, no, a patent licensing policy, the development organization and legal powers and applications, and things of that kind which we didn't know anything about.

Mr. COX. You didn't mean the 1924 contract?

Mr. LEVIS. The 1924 contract I didn't know of, other than it was in existence. I had never read it. That is when I went into Owens-Illinois.

Mr. COX. You feel today, I suppose, that your company should get the same treatment from Hartford-Empire that any other licensee gets, is that correct?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes.

Mr. COX. You have been successful, you think, in getting that kind of equitable treatment, Mr. Levis?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir.

AGREEMENT OF 1924

Mr. COX. Now I want to develop very briefly some of the provisions of that 1924 agreement; in case you feel you can't answer the question, perhaps Mr. Williams can. I am going to put the agreement in the record ultimately, but I would like to develop briefly the character of some of the provisions. Do you wish to have a copy of the contract before you?

Mr. WILLIAMS. I have a copy here, Mr. Cox.

Senator KING. Which contract is this?

Mr. COX. This is a cross-licensing contract made in 1924 between Owens-Illinois and Hartford-Empire. Under that contract it would be accurate to say that the two companies exchanged licenses, Mr. Williams?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes, each granted to the other a license under the patents that they then had, or would acquire within the time stated, limited, however, to feeders and feeder-fed forming machines.

Mr. COX. The suction machine was excluded?

Mr. WILLIAMS. That is right.

Mr. COX. Under that contract the Owens Company was to pay certain royalties to the Hartford Company, is that correct?

Mr. WILLIAMS. They had a most-favored-nation clause that they got as low royalties or as good royalties as anybody got, with one or two exceptions.

Mr. COX. One of those exceptions was the fact that they had the use of forty-three units of machinery, did they not, or not to exceed forty-three units of machinery?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes, although by the answer I meant with respect to certain other concerns that might have lower rates.

Mr. COX. I see, I beg your pardon, but that was an exception, at least it was a limit, a qualification of the royalties I speak of, the forty-three units.

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes.

Mr. COX. That was in Section 5 of the contract. Is that correct?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes.

Mr. COX. And under the contract, Hartford-Empire was to make certain payments to Owens. Is that correct?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes.

DIVISION OF INCOME

Mr. COX. And would it be a correct summary of one of the provisions as to those payments to say that Owens was to receive one-half of Hartford's divisible income from licensed inventions, as divisible income was defined in the agreement?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes.

Mr. COX. And divisible income was defined in the agreement as including gross royalties, license fees in excess of cost, profits on parts, damages collected in infringement suits, less the $600,000? That is in Section 1 if you would like to look at it, I think page 7 of that contract. I hope you have followed this, Mr. Levis, because I want to ask you some questions about it.

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes, there were five items. I think you mentioned the five, that is the income from licensed inventions.

There was the income derived from royalties; license fees in excess of cost of the manufacturing of licensed machines; profits on manufacturing, lease or sale of machines or parts; settlement for damages, and profits arising out of infringements of licensed inventions, and other gross revenues with exceptions as provided.

Mr. COX. That same contract provided in Section 1 in certain circumstances for the joint purchase of patent rights owned by others, is that correct?

Mr. WILLIAMS. No, not in Section 1, I think.

Mr. COX. Can you find that, Mr. Williams?

Mr. WILLIAMS. It is not in Section 1.

Mr. COX. I think Section 21, I beg your pardon.

Mr. WILLIAMS. I think that is correct, yes.

INFRINGEMENT PROSECUTIONS

Mr. COX. And in Section 8 of the contract there was a provision that each party should vigorously prosecute infringements of patents owned or controlled by it, at its own expense.

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes.

Mr. COX. But there was also in the same paragraph a provision that if the parties couldn't agree as to the suits which were to be brought, that disagreement was to be arbitrated. Is that correct?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes.

Mr. COX. I wish you would look at Section 22 of the contract, now, Mr. Williams, and tell me if that section provided that Hartford could not license anyone under the inventions which were covered in the cross-licensing agreement by Owens, without Owens' consent, except to existing licensees of Hartford for machines already installed or for additional machines, and to be used in the same fields covered by Hartford's existing licenses, or to any legitimate manufacturer who was defined as a glass manufacturer of good commercial and financial standing, who was not a commercial user of his own product, and the license was to be in his case the same kind of ware which he made one year previous to the date of the contract. Is that an accurate paraphrase of those provisions?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes, except that in the first class which you mentioned, not only the lines of ware or fields of ware covered by existing licenses, but also that might be covered by outstanding contracts. That limitation was taken out of the contract February 2, 1931.

CHANGES IN CONTRACT

Mr. COX. I was going to ask you about that. Maybe we might run through, very briefly, some of the subsequent changes in that contract. I will suggest them to you and you tell me whether they are correct in a general way.

In 1932 the Hartford-Owens license was changed from an exclusive to a non-exclusive license. Is that correct?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes, among other changes.

Mr. COX. Also certain other provisions were eliminated from the contract, such as the provision as to suits, and the joint acquisition of rights.

Mr. WILLIAMS. An entirely new contract was drawn, and this 1924 contract was cancelled.

Mr. COX. And a new contract eliminated the provisions as to joint acquisition of outside rights and the provision as to litigation.

Mr. WILLIAMS. I think that is correct.

Mr. COX. And, of course, in a separate contract in 1932, Owens got a license under certain suction patents of Hartford-Empire. Is that correct?

Mr. WILLIAMS. That is right.

Mr. COX. Is that an exclusive or non-exclusive license?

Mr. WILLIAMS. I think it was non-exclusive, but I can look at it and see.

Mr. COX. That was my understanding. At the same time the right to use forty free units was surrendered?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes.

Mr. COX. By the way, when you speak of a unit in that connection, it means one feeding and one forming machine?

Mr. WILLIAMS. It was so defined.

DIVISION OF INCOME.

Mr. COX. At the same time a change was made with respect to the divisible income so that Hartford-Empire was entitled to deduct $850,000 from its gross figure before dividing with Owens-Illinois. Is that correct?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Correct.

Mr. COX. And was any other change made at that time with respect wasn't it at that time that the amount which Owens was to receive was cut from one-half to one-third?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Correct.

Mr. COX. So that between 1924 and1932 Owens got one-half of Hartford-Empire's divisible income, as to the agreement from 1932, and until 1935 it received one-third.

Mr. WILLIAMS. That is correct.

Mr. COX. In 1935 another series of contracts were instituted as a result of which the right of Owens to receive any part of Hartford's divisible income was surrendered?

Mr. WILLIAMS. That is right.

Mr. COX. And in consideration of the execution of those contracts and in consideration of that surrender of that right, and perhaps some other matters, Hartford paid Owens $2,500,000 approximately.

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes, payable in installments.

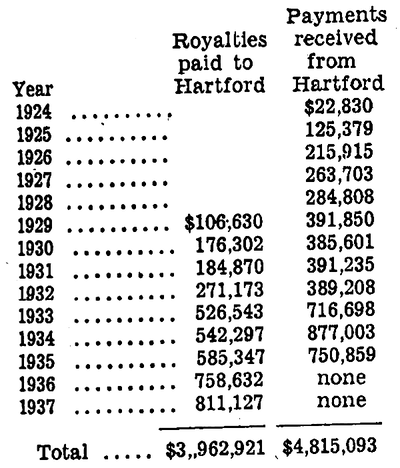

Mr. COX. Payable in installments. Well, now, Mr. Levis, I'd like to ask you some questions about that contract. In the first place I am going to show you a schedule of the payments made by Hartford to you under that contract between 1924 and 1937, and the payments made by you to Hartford. This was given to us by Mr. Martin. I ask you to identify those figures as being from your record and as being substantially correct.

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir.

Mr. COX. This schedule which I am shortly going to offer for the record shows that between 1924 and 1937 you paid in royalties to Hartford-Empire $3,962,921; you received in return under the 1924 contract from Hartford $4,815,093, so that there was a net return to you under that contract of about $800,000. Is that correct?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir.

Mr. COX. May I have this marked in evidence?

The CHAIRMAN. It may be marked and entered in the record.

(The schedule of Owens-Illinois payments to Hartford-Empire and receipts from Hartford-Empire from 1924 to 1937 was received in evidence and marked "Exhibit No.127" and is included in the appendix of this issue )

PROFIT ON PATENTS

Mr. COX. So at least on that contract, on that part of your patent licensing business, you did make some money, didn't you?

Mr. LEVIS. Not after the developments nor the legal expense that was involved. In fact, we never made any money, Mr. Cox, in our business in the whole of the patent situation or in a division of it.

Mr. COX. I will put it this way, the net result of the payments to and fro under that contract was that you ended the transaction on the credit side of the ledger so far as those payments are concerned.

Mr. LEVIS. Oh, yes, but I mean we can't segregate each carload of bottles and determine whether that is profitable or not. It is our bottle business as a whole, our patent business as a whole was unprofitable.

Mr. COX. That is taking the patent business in its entirety?

Mr. LEVIS. This is unprofitable if, accounting-wise, you would charge against the income our development and legal expense.

Mr. COX. Of course, this figure which I have read to you here doesn't include the two and one-half million dollars you received in 1935.

Mr. LEVIS. That was for the sale of patents, sir.

Mr. COX. Well, that wasn't a part of the consideration for that payment

Mr. LEVIS (interposing). Wasn't royalty.

Mr. COX. Wasn't that cancellation of your right to receive one-third of the divisible income of Hartford-Empire?

Mr. LEVIS. Well, it was for a settlement of everything from the selling of our patents and the cleaning up of a lot

Mr. COX (interposing). Including the surrender of your right to give up and receive.

Mr. LEVIS. But the two and one-half million dollars

Mr. COX (interposing). You included that in determining whether or not you made a profit on your whole?

Mr. LEVIS. The whole patent business, yes.

Mr. COX. Of course, between 1924 and 1932 you also had the free use of up to forty units of the Hartford-Empire machines?

Mr. LEVIS. So far as I know, it was never exercised.

FREE PATENT UNITS

Mr. COX. Will you refresh your recollection on that, Mr. Levis, because we have some documents from your file which would indicate that it was used.

Mr. LEVIS. Mr. Williams said that the Owens Company, before I came in, did have some free units.

Mr. COX. We have a document which would indicate that in 1929, just before you came in, they were using at least fifteen of those units. Would you think that was substantially correct?

Mr. WILLIAMS. I couldn't tell you the number of them, Mr. Cox, but I simply know there were free units.

Mr. LEVIS. I might point out just this, which I think explains it. Under the provisions of the contracts, when Owens acquired the assets of Illinois, Ilinois [sic] Illinois feeder licenses could have been surrendered and free licenses substituted for them up to forty, and that we never felt that that was the proper thing to do.

Mr. COX. Do you know if any, of the free feeder units, to which you were entitled under the contract, were used by Owens-Illinois between 1929

Mr. LEVIS (interposing). It was always my recollection that none were used; that we always paid our part of the rate.

Mr. COX. You think not one of those units

Mr. LEVIS (interposing). I may be mistaken, Mr. COX. Will you check on that, Mr. Levis?

Mr. LEVIS. I will check on that.

Mr. COX. You, on the other hand, Mr. Williams, are inclined to believe that at least up until 1929, with the five-year interval there, some of those free units were used by the Owens Bottle Company?

Mr. WILLIAMS. The Owens Bottle Company did have free units. I can't tell you just the period or just the number, but they did have some free units.

Mr. COX. They did use them to manufacture bottles?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes.

Mr. COX. Now, Mr. Levis, taking this contract in its entirety, let's consider it for a minute. Under that contract I may be

Senator KING (interposing). Are you speaking of the '24 or the later one?

Mr. COX. I am speaking first of the contract from 1924 to 1932. Under that contract your company received one-half of the divisible income of Hartford-Empire and also the use, if it cared to take advantage of the opportunity, of these free units?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir.

GLASS BOTTLE INDUSTRY

Mr. COX. Don't you think that provision in the contract gave the Owens Company a certain competitive advantage in the manufacture and the sale of bottles?

Mr. LEVIS. It would only be an opinion, sir, because I had nothing to do with the negotiation, but my opinion always was that the Owens Company had as valuable a feeder patent structure that was contributed to the Hartford Company's patent picture as Hartford then had, and that they were entitled to compensation for their contribution, and Mr. Williams might verify that.

Mr. WILLIAMS. That is right. When the contract was made in 1924, Owens contributed patent rights by license that it had and which it claimed dominated the Hartford machine. Litigation had been started and they were in for a free-for-all fight when this settlement was made.

Mr. COX. Will you give us the names of those patents, if you can?

Mr. WILLIAMS. The Bock patent, the Lott patent, and the Brookfield patent are the ones I recall, and there were many others listed in the schedules attached to the contract.

PATENT LITIGATION

Mr. COX. And it is true, is it not, when you spoke of litigation you refer to the suit the Owens Company had started against certain users of the Hartford-Empire feeders?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes, against one, 1think.

Mr. COX. So one of the circumstances which lead to the making of the 1924 contract, in your opinion , was the fact that the parties had patents which appeared to cover, at least each asserted that the patents covered machinery which accomplished the same result, and they were both threatened with litigation as a result of that situation.

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes, and if the claims of each were sustained in any major part, the result would be that neither could make a substantial or efficient feeder and each would be blocked by the other.

Mr. COX. Each would be blocked by the other?

Mr. WILLIAMS. That is correct.

Mr. COX. And as far as those companies were concerned, there wouldn't be any patents on automatic feeders effective?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Well, there would still be patents that each would have, but the difficulty came with the infringement that arose out of the use of any specific mechanism that either would make.

Mr. COX. The patent would be there, but it wouldn't be much good as a patent because there would be an effective right to sue for infringement?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Well, either party could have sued anyone who made a feeder that infringed his patent, so that the patents still had their value. The difficulty arose in the use of any mechanism that was covered in part or in whole by the patents of either.

Mr. COX. They might have been each suing each other?

Mr. WILLIAMS. Yes.

Mr. COX. Rather than face that situation, they made the contract and provided for the cross-licensing?

Mr. WILLIAMS. That's right.

REBATES ON ROYALTIES

Mr. COX. Well now, Mr. Levis, taking this provision providing for the division of the income of the Hartford-Empire, wasn't the effect of that that the Owens Company was getting a kind of rebate on all the royalties paid by other licensees of Hartford-Empire?

Mr. LEVIS. No, I don't think so, Mr. Cox. The Owens Company, back in 1904,developed a patent structure and they received royalties from many companies. They were in the royalty collecting and patent development game, just about like the Hartford people subsequently became.

Mr. COX. You mean they gave up that part of the business?

Mr. LEVIS. So far as they could have owned it in the licensing of feeders to their existing licensees and others. In fact, I don't know accurately, but it is my recollection that the Graham A. W. machine was licensed to Coshocton in 1917, to Glenshaw in 1918, to Turner in 1918, by the Owens Company, and that they were a feeder fed machine, and they went on in the development of their art and

Mr. COX (interposing). Are those the last licenses in point of time?

Mr. LEVIS. No. The 1932 license to Hazel-Atlas in July, and the October 31, 1935, to Hazel-Atlas, of which you have copies

Mr. COX (interposing). But aside from Hazel-Atlas, the three you have named are the last licenses that have been issued?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, that is our record.

Mr. COX. Prior to that time most of your licenses had been issued before 1914 and 1915?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes.

Mr. COX. Now if I understand your answer a moment ago, it was in effect that the result of the 1924 contract really was that the Owens Company gave up the business of licensing under its patents which might have provided some revenue for it , and turned that over to Hartford-Empire to manage for them, and they went on conducting their licensing in the suction field, extracting royalties from the Illinois Company, of which you were then president.

Mr. LEVIS. They carried on the business in the suction field, and the Hartford group carried it on in the feeder field and they got part of the income from that that they contributed to, and Hartford had contributed nothing to the suction field, therefore didn't participate.

Mr. COX. As far as other business in patents is concerned, Owens' last business in the stock licensing field was in 1915.

Mr. LEVIS. The last license was 1918.

Mr. COX. Most of them had been granted before that, up to 1915. Now, isn't it a fact, Mr. Levis, that under the provisions of the division of income, every licensee who was paying royalty to Hartford-Empire was in effect paying part of that, royalty to you, to your company I am speaking of the Owens Bottle Company and not the Owens-Illinois Company?

RETURN FOR ROYALTIES.

Mr. LEVIS. That is what actually happened, Mr. Cox, but as a matter of fact, as a bottle manufacturer, I think but very few of them ever thought of it as royalty. It was their contribution to the development of the art, the furnishing of a service on the part of Hartford which kept patent things straight and development things straight, and they didn't have departments like Owens, have big machine shops and patent linguists and patent draftsmen and solicitors, and all those things. They bought that for a fee to Hartford, who gave them splendid service and put them in a position to become better competitors in the industry because they acquired that service which made them better manufacturers.

Mr. COX. Part of the fee they paid for that went to you, to your company?

Mr. LEVIS. No, sir, we contributed certain patents and development and legal expense to them and they collected in the form of royalties for us. We never thought of it as our putting up nothing and taking in something.

Mr. COX. I am not suggesting that that was quite the situation, Mr. Levis. The point I wish to develop is this. Here were a large number of concerns engaged in manufacturing bottles, glass containers; they were licensees of the Hartford-Empire, and a great many of them, I suppose to a greater or less extent, were your competitors, were they not?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir.

Mr. COX. They were paying license fees, a royalty fee to Hartford-Empire, and a part of those royalty fees were being given to you under the provision of the division of income.

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, but, Mr. Cox, I ran the Owens-Illinois Glass Company from 1924 to 1929 and I not only paid Hartford royalties on patents, part of which they got, but paid royalties on patents, all of which they got, and never was unhappy about it.

Mr. COX. I am glad you mentioned that, because I want to ask about it. You were perfectly content with that situation, were you?

Mr. LEVIS. I stated so yesterday. We believed that we got more efficient devices and service in dealing with organizations of that type than if we had taken pirate devices.

COMPETITION: ITS VALUE.

Mr. COX. And you think that from the competitive point of view, that that was a perfectly proper thing for your competitors to be paying royalties to Hartford and having those royalties divided or rebated to you?

Mr. LEVIS. You have got to clear up who "you" is in this.

Mr. COX. I am not trying to fix you with personal responsibility.

Mr. LEVIS. I mean, Owens or Illinois?

Mr. COX. I am talking about Owens. I want your judgment on the thing as a man who has been in the glass business for a good many years. You think competition is a good thing, don't you, in the glass business?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir.

Mr. COX. I just want you to tell us whether you think that is the sort of condition that is conducive to healthy competition, when one company, and a large company, Mr. Levis, is getting a rebate of this kind.

Mr. LEVIS. It is improper to term it a rebate.

Mr. COX. I will withdraw that term. I will say a division of royalties of that kind.

Mr. LEVIS. If you want my personal opinion, Mr. Cox , as a man who has been in the glass business, I have never felt that the word "royalty" was a proper word.

PATENT DEVELOPMENTS

I always thought of our payment as a contribution to the development of the art, and that the people who collected that performed certain services for the manufacturer which he didn't have to perform himself. I always thought we got that service. We complained about it, but we complained about everything.

Mr. COX. Now, taking that definition, what service was Owens-Illinois performing for these licensees of Hartford-Empire that in your opinion justified the payment to Owens of a part of the royalties which the licensees were paying to Hartford-Empire?

Mr. LEVIS. They were collecting in installments the purchase price of the patents that they put into the group.

Mr. COX. Those are the gob feed patents that Mr. Williams spoke of?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes. And second, they were perfecting those, and any right that they developed in that connection flowed to Hartford as a part of the consideration for the payment.

Mr. COX. Throughout this period if you don't know, perhaps Mr. Williams can tell us whether the Owens Company was doing development work on the gob feed patent as distinguished from the suction.

Mr. LEVIS. Oh yes, anything we do goes to Hartford and he takes and gives to our competitor to use against us.

PREFERENTIAL TREATMENT

Mr. COX. But of course, so far as that situation existed between 1924 and 1935

when your competitor used the device, you in effect collected a royalty on it through this division of income.

Mr. LEVIS. We received a part of the divisible income.

Mr. COX. Then would you say, Mr. Levis, (and I want you to think very carefully about this) that it was never your policy or the policy of the Owens-Illinois Company, as long as you were connected with it, to receive better treatment from Hartford-Empire than other licensees in the field received?

Mr. LEVIS. Mr. Cox, that is a very broad question. If you limit it, I will try to answer it.

Mr. COX. Well, I will put it this way. Was it your policy to turn the whole patent and licensing business over to Hartford-Empire for development and exploitation and to receive in return a preferential treatment so far as the payment of royalties was concerned?

Mr. LEVIS. Mr. Cox, as I explained yesterday, my bringing up in this thing was different from that. When I came into the Owens-Illinois Company I knew very little about patent matters. They had a large investment in a licensing business. I was the president of the company and wanted to liquidate. I even sought to inaugurate a policy so far as their licensing business was concerned that we would pay no royalty to anyone, that everybody else would pay a royalty to someone and we would get just as much of that as we could. Now I found out, at least along in '33 and '34, that I was just swapping dollars and I was riding railroad trains and I wasn't making a dime, and as soon as I could convince the people who had grownup in the other field that my doctrine of this thing was right, we finally sold out and started on in our business, and as I said to you yesterday we were more successful after we did it.

POLICY AS TO ROYALTIES

Mr. COX. You found it didn't pay to try to make money out of the patent situation.

Mr. LEVIS. Even with the policy as I stated it, it didn't pay, because the time of our principals who had to devote their thinking to these interferences and litigation and how to keep from being excluded in fields was consumed away from the business features of our company.

Mr. COX. Then, if I understand you correctly, your purpose at one time was to create a situation where every one else in the field would pay a royalty for the inventions which they were using, and that your company would not pay a royalty to avoid doing so?

Mr. LEVIS. No, I don't think that was ever my purpose, Mr. Cox. Just like I would like to sell certain items cheaper, but there are certain factors in connection with an investment that we owned that I felt we must liquidate profitably, that I tried even to create a policy, and even if that policy had been 100 per cent successful, then that division of our business would not have been profitable, and consequently, having tried it for five years without success, I sought the policy of abandonment.

Mr. COX. You did make a change in policy?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir, changed my mind and it wasn't much different after I changed it than when I started, because the Illinois Company had been successful under the other policy.

Mr. COX. To the extent there was a change, it was a change from the policy which you say you inherited when youcame into the Owens company.

Mr. LEVIS. That is the way I think of it.

Mr. COX. I just want to get a precise definition of what that policy was that you inherited. I am going to show you a document which purports to be a copy of a pencil memorandum, and I call your attention to the paragraph I have marked.

Mr. LEVIS. Before I look at it, I want to correct you to this extent. This isn't the policy; this is my idea of to what extent we might go to try to make this division of our business possible.

Mr. COX. What are you describing now?

Mr. LEVIS. A restatement of your question that you were handing me something.

Mr. COX. Are you describing what this is that I have given you now?

Mr. LEVIS. No, I was answering your question in giving it to me.

Mr. COX. You look at that, Mr. Levis, and see that paragraph that I have marked. It is the paragraph which begins, "Our negotiations with Hartford-Empire Company and others . . . ."

Senator KING. Are you referring to the policy after 1934 or under the 1924 contract?

Mr. COX. I have to find out from the witness first when this memorandum was prepared. That is the next question I am going to ask him. It is undated. When was it prepared?

CHANGE IN ROYALTY POLICY

Mr. LEVIS. I don't know. I have no recollection of the memorandum. Some of your men went to Alton and took from my office personal files a lot of papers that my uncle had accumulated, evidently for sentimental reasons. I had no copy and this was one of them, and when I saw your typed copy of what one of my men who has been with me for many years said is not in my writing, it doesn't differ, though, sir, from what my thinking was as a kid in 1929, starting out to liquidate this undesirable part of this business.

Mr. COX. You think this substantially describes your attitude?

Mr. LEVIS. It describes what I might have been thinking but it doesn't describe what I think now.

Mr. COX. I understand that. What I am trying to find out now is what the precise policy was that you did change in1935 , and this is the policy that you did change.

Mr. LEVIS. We never were able to carry that out.

Mr. COX. That is what you were trying to do?

Mr. LEVIS. No, that is what I believed it would be necessary to do to make that division of our business profitable.

Mr. COX. I think perhaps we might read this so it will be clear what we are talking about. The paragraph reads: "Our negotiations with Hartford-Empire Company and others, so far as our patent situation and royalty income is concerned, should be to attempt to secure a position whereby we pay no royalty on any item we produce and we attempt to force all others to pay royalty on every item they produce, we participating with anyone else in the royalties they receive."

I suppose "they" means Hartford-Empire. That is the policy you thought you would have to adopt if you were going to make any money out of patents?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes. The early part of the memorandum tells of the policies I thought we would have to adopt if we were going to make money selling bottles.

Mr. COX. That is the policy you gave up in 1935?

Mr. LEVIS. No, I gave it up right along. I can't state what date I started to think differently. I had a right to change my mind. This was a memorandum evidently prepared for me to talk over with my uncle, who was an old head in the business, and when I got through spending the evening with him I probably left it with him. I don't see any economic significance to it.

Mr. COX. You have told us you changed the policy. I think I understand what the policy is today, so I am going to ask you about that in a moment, but I want to get a precise definition of some kind as to what the policy was you changed, and if this represents at least in one form the acme of that policy, or what you thought you might have to do to accomplish the result to which your prior policy was directed, I am content.

Mr. LEVIS. That is right.

ROYALTY POLICY SINCE 1935

Mr. COX. How would you describe your policy on patents today, Mr. Levis, or since 1935? I am going to ask you some questions later on about licensing. Let's confine it now to the collection of royalties paid by others manufacturing bottles. Are you interested in collecting royalties from other persons who are engaged in manufacturing bottles and who are competing with you?

Mr. LEVIS. No, sir.

Mr. COX. That has been your policy since 1935?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir.

Mr. COX. Do you collect any royalties today from anyone engaged in manufacturing bottles in competition with you?

Mr. LEVIS. We have a few small contracts, like the Dominion Glass Company, who really aren't in competition with us, and we have some small income from gadgets like decorating and items of that kind, but certainly we have no competitive advantages as a result of royalty income.

ROYALTIES COLLECTED

Mr. COX. You don't get any royalties from any of the large companies manufacturing glass containers, such as Hazel-Atlas and Ball Brothers? I am speaking of the period of time since 1935.

Mr. LEVIS. Our royalties received in the years '36 and '37 amounted to $2,690,000 in the year '36 , of which $2,624,000 was paid by ourselves; $12,752 by the Dominion Glass Company; $1,179 by the Thatcher Company; $614 from foreign sources. There are a number of other small items that don't relate to glass. Does that answer your question?

Mr. COX. That answers the question. When you say you paid them yourselves

Mr. LEVIS (interpolating). It is simply bookkeeping. In other words, in determining our cost we like to have in, as an element of cost, royalties, even though we charge them to ourselves.

RESTRICTION ON LICENSES

Mr. COX. All right; I think that answers my question.

Now, Mr. Levis, I want to ask you some questions about Section 22 under the 1924 contract, which I think you said a moment ago was withdrawn in 1931, or Mr. Williams said that.

Do you recall that was a provision which prevented Hartford from licensing people under your patents without your consent, except in the specific cases mentioned there, which in effect might be summarized by saying they could be given only to people who were in business or under license to Hartford at the time the contract was made? That section was taken out of the contract in '30 or '31, I think, after you came into the Owens-Illinois Company.

Mr. COX. Tell us why that was taken out.

Mr. LEVIS. All I know is that when I came there I was advised that it never had been exercised and Mr. Williams asked to have it removed from the contract, and I thought if it wasn't an essential feature was willing that that be done.

ANTITRUST LAWS

Mr. COX. Was one of the reasons, Mr. Williams, why you thought it better betaken out because it raised some question under the antitrust laws?

Mr. WILLIAMS. It was the one vulnerable spot, I thought, in the contract, or rather the provision that would raise objections. I objected to putting it in in the first place and was overruled.

Mr. COX. When you took that provision out, did it make any difference in the nature of your relationships with Hartford-Empire at all?

Mr. LEVIS. No. So far as I was concerned, I was advised that it had never been used and Mr. Williams, for some rea-on, didn't want it in, and I didn't see any reason why it should have been in anyway.

Mr. COX. Isn't one reason why you took it out because you felt sure Hartford-Empire wasn't going to grant licenses recklessly or in disregard of your interests?

Mr. LEVIS. Oh, no.

Mr. COX. I am going to read to you a paragraph of a memorandum which was sent to you by Mr. Carter, who, I understand, is your vice-president in charge of your patent section in your legal department. Is that correct?

Mr. LEVIS. He was.

Mr. COX. This memorandum is dated December 13, 1930. It reads as follows:

"The objection on our part to eliminating Section 22 is the fear that Hartford, once freed of our veto, might be inclined to grant licenses recklessly and without regard to the state of the market or good of the industry. Believe that this fear is much exaggerated. We have been dealing with Hartford under our 1924 agreement for more than six years now and have never found any tendency on their part to act recklessly or in disregard of basic conditions. Believe we may safely conclude that their attitude in the future will not be different."

I ask you if that is not a statement of a reason for agreeing to the abolition of the section which is in substantial agreement with my question to you a moment ago?

Mr. LEVIS. Mr. Cox, when I got to Toledo in April about every twenty minutes I got six memorandums like that. I just couldn't read them. They didn't have anything to do with the business. You take my early '29 memorandums, all of which you have, and they don't differ at all in the theories I explained. Maybe there is some trade talk in some memorandum Mr. Carter did, but my way of handling this business hasn't been a darned bit different, and the way my early memorandums indicated I was raised. That memorandum had no effect on me. I was simply a young fellow in there and they said, "Mr. Williams would like this paragraph out of the contract," and I said. "Well, have you ever used it?" They said, "No." I said, "It doesn't amount to anything anyway, so take it out."

As to what Hartford would do, as to whether they would do something we asked them to or not, I don't think that ever worried us.

Mr. COX. Weren't you interested in the persons to whom they granted licenses?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes. I think other bottle manufacturers were more interested in it than we were.

Mr. COX. But you were interested in it to some extent?

Mr. LEVIS. Oh, yes, but we had the largest percentage of our production on our own royalty-free machines. At that time we had a participation for the patents we contributed to in the 1924 Hartford contract.

Mr. COX . Isn't it a fact that even since the abolition of this provision in the contract you have talked to Hartford-Empire and consulted with them about the wisdom and propriety of granting licenses under their patents?

Mr. LEVIS. I may have, Mr. Cox. I complain and talk about things of that kind, just like I would about some enactment of legislation I might not like, but as for ever believing that I could, other than through my own personal persuasion ,get some fellow to do something because I had a contract with him to force him to do it, I didn't.

Mr. COX. You did at least offer your advice or suggestions on that?

Mr. LEVIS. Oh, I offer that freely, sir, to everybody in the glass industry, and lots of them take it.

Mr. COX. Have you ever suggested or advised Hartford that in your opinion they should be careful about granting licenses to people who want to go into the business of manufacturing bottles and containers?

Mr. LEVIS. I may have, sir, but I don't recall the incident.

Mr. COX. I am thinking generally now. I have one instance that occurred in 1933 and I am going to ask you about in a moment, but I just want to ask you now if you had any general statement on that that you wanted to make.

Mr. LEVIS. I don't believe, Mr. Cox,that I feel at all that I have anything todo with that.

BEVERAGE BOTTLES

Mr. COX. Now, Mr. Levis, I am going to read to you a letter which you wrote January 13, 1933, to Mr. F. Goodwin Smith. It reads as follows:

"My dear Goodwin: Referring to Mr. Northend's letter of January 10th regarding the persistent letters he has received from Mr. E. C. Devlin, I am replying to you rather than to him because I feel that you should know that the old Northern Glass Company plant never was operated successfully and that I do not think we should be at all concerned regarding their thoughts of resuming operation.

"We are in splendid shape to take care of Milwaukee trade from our Streator, Illinois, plant, and while I want to keep posted from time to time about people who inquire for licenses for the manufacture of beverage bottles, I think the position that you are taking that there is at present considerable over-production in the industry should be maintained in replies to similar requests."

I ask you if you in fact wrote that letter to Mr. Smith.

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir.

Mr. COX. That was a situation, was it not, where Mr. Devlin had been writing to Mr. Smith about getting a license and Mr. Northend had written to you about it?

Mr. LEVIS. He probably had, Mr. Cox. I can't remember that.

Mr. COX. You don't remember anything about it?

Mr. LEVIS. It is just one of many things in ten years' work.

Mr. COX. The correspondence you had with Hartford involved a request that had been made to them for license for use in a glass factory plant somewhere in the neighborhood of Milwaukee. Does that refresh your recollection at all?

Mr. LEVIS. No, sir. There may have been many such letters, and I may have answered them in that same way.

Mr. COX. Was it your position at that time that you wanted to keep posted from time to time about people who inquired for licenses for the manufacture of beverage bottles?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir.

Mr. COX. Why did you want to be posted?

Mr. LEVIS. I wanted to be posted on everything.

Mr. COX. Was that just curiosity, or did you have some specific purpose in mind that you wanted the information for?

Mr. LEVIS . I don't think I had any specific purpose, Mr. Cox.

Mr. COX. If I should suggest to you that what you really wanted to know was who was asking Hartford for a license for that purpose, so you could discuss with Hartford whether the license should or should not be granted, would you repudiate that suggestion?

Mr. LEVIS. I wouldn't repudiate any suggestion, Mr. Cox. You have 8,000 pieces of my papers. I will try to help you in working any of those out, but I just can't remember each isolated letter that I wrote to Goodwin Smith. Show me the incident, and if I can refresh my memory I will tell you the truth.

Mr. COX. I am sure you will, Mr. Levis. I am not asking you now about a particular incident. I am asking you about the general statement you make that you want to keep posted from time to time about people who inquire for licenses for the manufacture of beverage bottles. You said you wanted to keep posted about everything, and I still want to know whether you wanted to know about people who inquired as to beverage bottles merely out of curiosity or because you were interested in seeing that too many of them didn't go into business.

Mr. LEVIS. I had no way of controlling whether they went into business. I was interested in protecting my own business.

Mr. COX. Of course, you could talk to Mr. Goodwin Smith about it?

Mr. LEVIS. I could talk to anyone in the industry about it.

Mr. COX. In your very persuasive manner, Mr. Levis?

Mr. LEVIS. Well

OVER-PRODUCTION POLICY

Mr. COX. (interposing). Now I call your attention to this last sentence in the letter: "I think the position that you are taking that there is at present considerable over-production in the industry should be maintained in replies to similar requests." Was that your position at that time?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, I think that was the position of all glass manufacturers at that time. I think that any licensee of the Hartford Company would have told Mr. Smith that same thing.

Mr. COX. It was a situation where it wasn't desirable to grant any more licenses?

Mr. LEVIS. The banks had just all been closed and we were in the peak of the depression with a tremendous over-production.

Mr. COX. Is that your attitude today? Do you think there is over-production today?

Mr. LEVIS. In the glass industry? Yes, sir.

Mr. COX. And would you say that you think because of that over-production licenses should not be granted by Hartford-Empire to people who apply for the right to go into business?

Mr. LEVIS. I have nothing to do with Hartford-Empire, sir, and I don't know what they would do. So far as I am concerned, I think that there are plenty of people in the business and there is an over-production.

Mr. COX. Would it be correct for me to say that if you had occasion to write a letter today to Mr. Smith like the letter you wrote in 1933, your advice to him would be the same?

Mr. LEVIS. My advice to him would be that I think there is an overproduction.

Mr. COX. And that no more licenses should be granted?

Mr. LEVIS. I don't think would add that now.

PATENTS AS STABILIZERS

Mr. COX. As a matter of fact, you have from time to time been interested in the use of patents as a device for stabilizing conditions in the industry, haven't you, Mr. Levis?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir.

Mr. COX. And of course the best way that can be done is through Hartford-Empire, since they are the license-granting organization in the real sense, aren't they?

Mr. LEVIS. We are too, Mr. Cox.

Mr. COX. You haven't granted any, though, since 1918.

Mr. LEVIS. Nobody has either the capital with which to buy one of our complicated machines, or the organization capable of making it work.

COST OF GLASS MACHINES

Mr. COX. That is very interesting. Are your machines very expensive to buy?

Mr. LEVIS. Expensive to build.

Mr. COX. To build, I mean.

Mr. LEVIS. Yes.

Mr. COX. Can you tell us about that? Why is that?

Mr. LEVIS. Because they are precision machines.

Mr. COX. Have to have special dies?

M. LEVIS. Yes. I think we made $65,000 for the last ten-arm machine.

Mr. COX. If a man wanted to go into business, to get a license from you and build a suction machine would cost him about $65,000 to build one machine?

Mr. LEVIS. It might cost him more than that to build the first one.

PRICE-CUTTING

Mr. COX. Returning for a moment to the use of patents to stabilize the industry, you said you were interested in that from time to time. In that kind of stabilization do you include elimination of price cutting, stabilization of prices on any line of ware?

Representative SUMNERS. Mr. Cox. At some time would you develop the cost of installing an efficient unit to produce these glass bottles? I mean to establish a business, a small business, but a business sufficiently complete to produce the finished article that would require some place to melt the sand and whatever goes with it.

COSTS OF PRODUCTION

Mr. COX. I will do that through these witnesses if I can, so far as their particular kinds of machinery are concerned, and through other witnesses as to other kinds of machines.

Representative SUMNERS. I wouldn't want to take too much time, but it would be interesting.

Mr. COX. Perhaps Mr. Levis can tell us about that.

Mr. LEVIS. Very briefly, sir, (we have always analyzed it) it costs about $500,000 per furnace to go into the glass container business, that is the furnace that melts the glass, the forming devices for making the ware, and the annealing ovens, with their buildings and packing house facilities. Another $100,000 should be added to cover compressors, and office facilities and machine shop, and about half a million dollars working capital, or $400,000 to make a round number, requiring about a million dollars invested capital, which you would turn once in the production from that furnace, about a million dollars in sales. That wouldn't make any difference, sir, whether that had our suction machine on it, or, say we put two suction machines to draw 100 tons, or whether we put six or seven Hartford machines on to draw that same tonnage.

EXPENSE OF ROYALTIES

The CHAIRMAN. It would make a big difference, however, Mr. Levis, whether or not you had to pay any actual royalty.

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir, except that you would be paying the royalties well, it is like a suit of clothes in the expense account; if you have to go through the development and work out the applications and work out the interferences in the patents, you spend it that way, or you pay Hartford a fee for their service.

The CHAIRMAN. I was comparing this typical plant which you have just described with your plant, and considering the position that it would occupy as a competitor of your company. When you were giving your figures on royalty a few moments ago, I was struck by the fact that as a rule you recited that about two and a half million dollars will be charged against yourself as royalties, as an item of cost. In other words, actually you didn't pay that royalty.

Mr. LEVIS. We paid more than $600,000 of it to Hartford.

The CHAIRMAN. Yes, but two and a half million, as I recall

Mr. LEVIS (interposing). It is 5 percent of selling cost, roughly.

The CHAIRMAN. This is the point I am getting at. Whatever it was, two million or two and a half million, there was a substantial portion of that royalty which actually never was paid to anybody. You charged it against yourself as an item of cost. Now I gather from an accounting procedure your purpose in doing that was to make certain that into the price of the article which you sold would go this element of royalties which your competitors were actually paying upon all their machines. Is that right?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir, but if I might carry on briefly, we then credit that to a so-called holding division as income to that division, and then we charge that division for our experimental and development expense, and our patent and license expense, and our legal expense, and the holding division consumes that. In other words, we spent $1,811,000 of that $2,000,000 last year that we charged ourselves two million six for use in research and development alone.

The CHAIRMAN. I thought that you had practically shed yourself of that element.

Mr. LEVIS. Oh, not on the suction, sir. I tried to make it clear yesterday that we are always taking out patents on that.

EXPENSE OF RESEARCH

The CHAIRMAN. So that of this two and a half million charged to yourself as royalties, but not actually paid as royalties, there were actually $1,800,000 expended in research or similar activities. Is that correct?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir. We then paid, of that that we received

The CHAIRMAN (interposing). I am not interested in the exact figure, Mr. Levis. I was merely trying to determine whether or not that was an actual item overhead, actually laid out or not.

Mr. LEVIS. No, we actually charged the bottle division of our parent company with royalty at 5 per cent of their selling price, and if they owe Hartford something, the holding division, which we call it, pays Hartford the royalties, and it spends the rest of that money in research and development, patent and legal and general overhead.

The CHAIRMAN. If the actual amount were computed only, instead of just this arbitrary amount of 7 per cent, would that be smaller?

Mr. LEVIS. No, it would be about the same. It figures 5 per cent.

The CHAIRMAN. So that I would not be justified in drawing an inference that if you didn't make this charge for royalty on an arbitrary basis but charged only the actual expenditures for these various items, you would be in a position to sell your bottles more cheaply.

Mr. LEVIS. No, they are about the same, sir. In this million-dollar mythical factory which I described, the royalty would be roughly $50,000. I don't believe that a small manufacturer today for $50,000 could have adequate engineering and patent counsel and other talent, such as they buy from Hartford for that fifty.

The CHAIRMAN. Are you in such a position with respect to royalties and your relations with the Hartford-Empire that you actually have an advantage over other licensees of Hartford in the production of glass containers?

Mr. LEVIS. That is a very difficult question to answer.

The CHAIRMAN. Of course, I would say it would be a perfectly natural thing for you to try to get into that position because you are in the business of producing bottles and making money, and if you can make money out of royalties that are paid by your competitors, that is a perfectly normal and natural thing for you to do. We are just anxious to find out whether that is actually the fact.

FACTORY COSTS

Mr. LEVIS. I might answer that by saying this, sir, that the mythical factory I said would put up $500,000 for a furnace. I believe that the smaller manufacturers 'in the industry investment in their furnace is probably $300,000, while ours, sir, is about a million. We have elaborate machine shops and machine tools for doing precision work, and a trained personnel that can operate necessarily complicated machines. In fact, on the Pacific Coast where we have built a new plant it cost us about ten million dollars.

We have put in Hartford equipment not because we don't believe our equipment would not be superior, but because we don't want to make the further investment for precision tools to make parts on the Coast, and molds, and we aren't capable of training on the Coast yet labor that can operate these complicated machines. Therefore, if we have an advantage, sir, it is because we have a different article for producing containers than Hartford licenses.

CHANCE FOR NEW PLANTS

The CHAIRMAN. The whole glass industry is now in such a position with respect to demand and production and the number of plants that are going, and the method by which patents are operating, that it would be an extremely difficult thing for any new independent concern to break into the field. Is that a correct assumption?

Mr. LEVIS. No, sir.

The CHAIRMAN. You think it would be possible?

Mr. LEVIS. I think they could get in, yes, sir.

The CHAIRMAN. Where would they get the license?

Mr. LEVIS. I don't think Hartford would object to granting them a license.

The CHAIRMAN. You think that Hartford, in the light of the testimony that was given here by Mr. Smith on the opening day, would be willing to grant licenses to new concerns for the production of containers, of which you say there is now an over-production?

Mr. LEVIS. I don't see that it would be anything to Mr. Smith's advantage. In other words, he can't get any more royalty and he might as well deal with others.

LICENSES FOR NEW COMPETITORS

The CHAIRMAN. He testified very candidly that his purpose in managing the patents and the licenses was to prevent the ups and downs in the industry, to prevent depressions, to do for the glass industry what this Committee is trying to find a way of doing for all industry, if it can be done, with the preservation of the antitrust laws. So in those circumstances, with that purpose in mind to protect over-production and thereby to prevent a dropping of price would it in all these circumstances permit a new competitor to enter the field?

Mr. LEVIS. I don't know that he would, but I believe that Hartford and Company have always been liberal in granting licenses to anybody who should be of a business type.

The CHAIRMAN. But liberal within these broad boundaries of maintaining the stability of the industry, which is a polite way of saying of maintaining the price and of maintaining the market and of preventing competition from coming in.

FAILURES IN INDUSTRY

Mr. LEVIS. No, sir, I don't think that is the fact, because the Glass Container Association have prepared a very interesting report on the industry, and they show that since 1920 that in 1920 there were 80 companies, and during the eighteen-year period 20 new companies came into the industry, 29 companies have failed or gone out of the industry and 26 companies have been consolidated in other companies of the industry. So in 1938 we have 45 companies in the industry. All of these data that these gentlemen have prepared show schedules of this mortality, that these men who enter

Mr. OLIPHANT. How many went out of business?

Mr. LEVIS. Twenty-nine, sir.

Representative SUMNERS. Did any of the concerns use the old method?

Mr. LEVIS. I couldn't answer that, but the report which I have a copy of here shows the mortality and the names, and from those names I could answer.

POLICIES ON LICENSES

Mr. ARNOLD. Putting the same question a little differently, not in terms of guessing what Mr. Smith's policy might be or in terms of what your policy might be in case you changed it again, or someone else took your place, it is certainly true that these private companies have the power to do exactly what Senator O'Mahoney was speaking of. Haven't they?

Mr. LEVIS. I don't know, sir.

Mr. ARNOLD. They have the power now to grant the licenses along the suggestions made in your letter of January 13, 1933. Now whether they do that or not is, of course, a guess, but they have the power.

Mr. LEVIS. They might have the legal right not to license someone, I presume.

Mr. ARNOLD. And so this power does exist in private hands to stabilize an industry with respect to price and with respect to production. Now, I understand that you believe in using that power liberally, but the power does exist there, doesn't it?

Mr. LEVIS. I don't believe that I can answer that, sir.

ROYALTIES AND RESEARCH

Mr. ARNOLD. Never mind, let me ask you another question with respect to the charge of $2,000,000 for royalties to your-self. It seems to almost equal the amount that you spent on research, doesn't it?

Mr. LEVIS . It is a little bit less than what we spent on research and pay to Hartford.

Mr. ARNOLD. Approximately they are equal then. Does that indicate that it would be patient policy as a matter of law to make the amount which could be collected on research about equivalent to the amount you collected in royalties where the invention was held by a group and where the question of equitably rewarding some particular inventor was not an issue?

Mr. LEVIS. I think, sir, you only have one qualification to that, a new business that is starting up couldn't survive with just that protection. An industry that has arrived in the stage of development that our industry has could probably con-sider adopting that policy.

Mr. ARNOLD. Then, with that qualification, if it is a good policy for your industry with the qualification that you mentioned might it not be a good legislative policy?

Mr. LEVIS. I don't believe I can answer that, sir, unless you insist.

Mr. ARNOLD. No, I wouldn't; it is an opinion. If you haven't any opinion, I wouldn't press you.

Senator KING. May I ask a question? Has your organization licensed any of its patent devices?

LICENSES ON PATENT DEVICES

Mr. LEWIS. Not since 1935; I mean, their only licenses were, as Mr. Cox explained, up to about 1914, and three small licenses were granted: One, in '17 and another in '18 and another in '18, and in '32 that Hazel revision.

Mr. COX. Of course, that was a revision of the existing license. That first license to Hazel was made before 1914. It was made about 1909.

Senator KING. Do you utilize your own devices in the manufacture of glass?

Mr. LEVIS. Exclusively, sir.

Senator KING. Do you regard them as comparable to the patents of the Hartford Company?

Mr. LEVIS. We regard them as superior, sir.

Senator KING. Why did you not use your own devices I think you explained it; pardon me for asking if it is a repetition in the new plant which cost you ten million dollars in California?

Mr. LEVIS. Because we didn't want to add further invested capital for the ma-chine tools to take care of the necessary equipment, and we didn't have trained personnel for the operating of precision equipment.

THE COST OF EQUIPMENT

"Senator KING . What would it cost for the purpose of manufacturing necessary dies and constructing the plant?

Mr. LEVIS. Our investment has always been an investment of about a million. I believe the smaller manufacturer has an investment of $300,000. Our investment is approximately a million, and that difference between his $300,000 and our million is in this precision equipment, better working facilities in shops, which they engage on the outside. In other words, we manufacture corrugated boxes, they buy them; we make molds, they buy them; we make machine parts; they buy them.

SELLING COSTS

Senator KING. Is it essential in the establishment of an industry to have a selling agency or to have an organization for the purpose of finding markets for the production; and, if so, state whether there is a considerable item of cost which must be taken into account in the launching of the firm.

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, we have always figured selling, administrative and general expense at about 10 per cent, and we have always believed we should have our own branches which are manned by salaried people rather than commissioned employees.

Senator KING. But it would require a larger sum in the initial stages of the development of an organization than would be required later on after it had been running full blast.

Mr. LEVIS. I think it gets a little cheaper as you go along, sir.

Representative SUMNERS. I meant to ask you a question or two a moment ago but my line of interrogation was interrupted. May I ask you this question? You speak of the installation of your factory. Do you have to make your own equipment, mechanical equipment, or is there some plant that manufactures it for the market?

Mr. LEVIS. We manufacture all of ours, sir, except certain machines that Hartford manufactures.

Representative SUMNERS. Do they have a plant where they manufacture these machines?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, you can buy bottle-forming machines or you can make them. We make our own.

PRODUCTION OF MACHINES

Representative SUMNERS. You spoke of the requirement with reference to exactness of the machine. Is there any market where you can go and buy such machines as you would like to install on the Pacific Coast?

Mr. LEVIS. No, sir, not our suction machine. We are the only one who makes it.

Representative SUMNERS. Do you make that for the trade or only for yourselves?

Mr. LEVIS. For ourselves. If someone wanted a license I presume we would grant it.

Representative SUMNERS. I am trying to get the picture. Do you keep a plant that is constantly operating, where somebody goes in there and says, that is the plant that manufactures machinery that makes glass?

Mr. LEVIS. We do, yes, sir, at Alton, Illinois.

Representative SUMNERS. Now if a person wanted to go into the manufacture of glass and wanted the machinery which would enable him to compete in that production, that field of activity, how many concerns could keep him from doing that if they wanted to? There is your plant, you are one sort, then there is the Hartford plant which has another sort. If those two would not be willing for him.to engage in the production of glassware containers, could he do it?

Mr. LEVIS. He can buy certain other machines: The Roiramt machine has been advertised in this country for years, and some of them are installed. I am informed that over 500 of them are operating in Europe.

Representative SUMNERS. Is that comparable in efficiency and economy to the machines that operate in your plant and that Hartford-Empire Company control?

Mr. LEVIS. It is different in type from Hartford. It is about the same as our six-arm machines, a number of which we have in operation.

ENTRANCE OF COMPETITORS

Representative SUMNERS. I don't know about the six-arm machine. What I am trying to find is the one thing. A person with a factory equipped with machinery that can be bought in the open market, would he have as a matter of competitive conditions an opportunity to stay in the market?

Mr. LEVIS. We are operating six-arm suction machines that are about the same as the Roiramt machine, at certain of our plants today. We believe that we can do that because over a period of forty or fifty years we have trained personnel capable of doing it. I don't believe that a new-comer can just walk out and hire a glass factory machinist and hire a glass factory engineer and enter into this business, regardless of license restrictions.

Representative SUMNERS. What we are trying to get here on this committee is as nearly a correct picture as we can get of the situation. Now taking this machine that you have just mentioned, if three persons of equal ability were under taking to produce glassware containers, one who had your machine, one who had the Hartford machine, and one who had this machine that you mentioned that may be bought in the market, as a matter of practical business competition would the third man with the machine that you have just mentioned have a chance to stay in the market?

Mr. LEVIS. If he was of equal ability, he would have a chance.

Representative SUMNERS. Make everything equal; just the question of difference in machine.

Mr. LEVIS. You can't make it equal unless he can buy the engineering service from Hartford, or from us.

Representative SUMNERS. Well, assuming that he can buy everything.

Mr. OLIPHANT. Assuming he can't buy from Hartford or them.

Mr. LEVIS. If he could buy that service from someone who was trained in the business

Mr. OLIPHANT (interposing). Can't he? Isn't there such a thing?

Mr. LEVIS. I would sell it to him.

Representative SUMNERS. But I am trying to draw a distinction between human ability and machine efficiency.

Mr. LEVIS. But you lost track, sir, that the "know how" is the esential [sic] essential thing.

Representative SUMNERS. That is human ability. You can't manufacture it. You can train it but you can't run it through a machine shop.

Mr. LEVIS. And very few people can acquire it.

Representative SUMNERS. But you don't get any patent right on human ability.

Mr. LEVIS. That is why you don't need a patent right if you have the "know how."

Representative SUMNERS. Let's get that pretty straight. When you, then, train a personnel, you no longer need a patent, is that right?

Mr. LEVIS. I have explained technically to Mr. Borkin

Representative SUMNERS (interposing). Explain it untechnically so I can understand it.

Mr. LEVIS. If I may refer to this, sir, I say, "The management of the large company in an established business is not concerned regarding the license or patentor compulsory licensing laws. If a company engaged in an established business on a large scale has the right to use all inventions at a fair royalty, it would save large sums of money."

Representative SUMNERS. I quite remember that testimony. In other words, you are already established and you have your market and you have your trained personnel; if nobody else can have a patent, then you are willing not to have any patents for anybody, is that right?

Mr. LEVIS. No, sir. I don't want to make it appear technical, sir, but I can't answer it otherwise.

Mr. ARNOLD. Mr. Levis, you put in a condition that I am interested in.

NEW COMPETITORS

Representative SUMNERS. But he hasn't answered my question, if my col-league will pardon me. I want to get this answered. You see, I am not smart like you boys. It seems to me from our standpoint, what we are trying to find out are just a few things, and we have got a good deal of evidence on some things.

First, we discover from the testimony here that there are a few big concerns that largely control the patents, that govern the manufacture of glass containers. Then of course there has been testimony about suits and about the notions of persons who have this control.

What I want to know and I believe my colleagues on the committee, would like to know is whether or not there is a possibility of an individual person who wants to establish a plant or factory, being able to procure the machinery that would enable him in turn to be a competitor of you people in so far as machinery is concerned. Of course, if you hire the brains, that is different. You can't patent that, I guess.

Mr. LEVIS. Or if he wants to pay us what is a fair compensation for the "know how," for the training, the engineering drawings that we have worked up in our business, we will gladly let him have one of our machines.

Representative SUMNERS. To establish a serious competition, a new serious competition for your plant?

Mr. OLIPHANT. To get that Milwaukee bottle business?

Mr. LEVIS. Oh, yes, sir.

Mr. COX. Of course, you haven't granted any license to new people in the industry.

Mr. LEVIS. There hasn't been anybody that I know of who has developed the technic capable of operating one of our machines.

Representative SUMNERS. Now wait a minute, Mr. Cox, you have just been asking more questions. You know, we are just trying to get that. I would like to have it myself. If you can answer it you haven't

Mr. LEVIS (interposing). I can answer it, sir, if you will be patient with me and tell me what you want answered.

Senator BORAH. Let's take lunch first.

FOREIGN MACHINES

The CHAIRMAN. Before we take lunch, may I ask one question, Mr. Levis? As I understood your first answer to Congressman Sumners, you said that there was one foreign machine which this mythical competitor could obtain, that it was possible, and then you compared that machine, that foreign machine, with some six-arm suction machine of yours, did you not?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir.

The CHAIRMAN. That was the first time that I remember having heard anybody mention the six-arm machine. Now my own question to you is this: Is that six-arm machine your most efficient machine?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes and no. It is the most efficient for making a variety of various sizes for scheduling, and less efficient for making long straight runs. In other words, we couldn't operate our factory without it, and we couldn't operate and be competitive exclusively with it.

The CHAIRMAN. And how many other machines do you use in comparison with this, proportionately?

Mr. LEVIS: It is all to the capacity, sir. We have fifteen-head machines that make two bottles at a time and ten-head machines that make two and a half, and six-head machines.

The CHAIRMAN. But the answer to the original question of Judge Sumners is this: that a competitor who was using only that single foreign machine (since it is comparable to your six-arm machine which is a machine which, while necessary for your business, is not sufficient to enable you to maintain it as a whole), would not be able to enter the field in which you are operating.

Mr. LEVIS. No one else has ever sought to enter the field we are operating.

Representative SUMNERS. Could you make milk bottles? Could you stay in business using that sort of machine making milk bottles in competition with an organization like Owens?

Mr. LEVIS. Yes, sir.

MACHINES VS. MEN.

Representative SUMNERS. Have you really got my question? By using this machine that you have just been discussing, a competitor could successfully compete with you, using your other machinery and making milk bottles?

Mr. LEVIS. Mr. Representative, I don't believe anybody could successfully compete with me in this thing. It isn't just a machine.

Representative SUMNERS. I know. They couldn't get your ability, possibly, and I am not speaking facetiously at all; we appreciate that, but we are talking about machinery now. That is what the patent is on, you know. We are not talking about nice personnel and good lawyers and efficient people; we are talking about machinery. If that is so, why don't you use that machinery instead of the other kind you use?

Mr. LEVIS. We do.

Representative SUMNERS. I mean to make milk bottles.

Mr. LEVIS. Because we happen to make milk bottles at Columbus and Clarion and probably it would cost us one million dollars to take the machine out and put this in.

Representative SUMNERS. Is that a new machine?

Mr. LEVIS. Newer than the ones we are operating. But, sir, it isn't the machine. I can take good personnel and at twenty-year-old machine and make bottles more efficiently than an average personnel and a modern machine.

Representative SUMNERS. Why have patents around here bothering people anyhow?

Mr. LEVIS. I am not bothering them. I stated my patent policy yesterday.