[Trade Journal]

Publication: Verbatim Record of the Proceedings of the Temporary National Economic Committee

Washington, DC, United States

vol. 1, no. 7, p. 1,193-232,Appendix 25-28, col. 1-3

VERBATIM RECORD

of the

Proceedings of the

TEMPORARY NATIONAL

ECONOMIC COMMITTEE

VOLUME 1

December 1, 1938 to January 20, 1939

CONTAINING

Economic Prologue

Automobile Patent Hearings

Glass Container Patent Hearings

Presentation on Patents by Department of Commerce

Published 1939 by

THE BUREAU OF NATIONAL AFFAIRS, INC.

WASHINGTON, D. C.

·

·

Sixth Day's Session

_____________________

VERBATIM RECORD

of the Proceedings of the

Temporary National Economic Committee

Vol. 1, No. 7 WASHINGTON, D. C. Dec. 12, 1938

MONDAY, DECEMBER 12, 1938.

THE TEMPORARY NATIONAL ECONOMIC COMMITTEE MET AT 10:45 A. M. PURSUANT TO ADJOURNMENT ON TUESDAY, DECEMBER 6, 1938, IN THE OLD CAUCUS ROOM, SENATE OFFICE BUILDING, SENATOR JOSEPH C. O'MAHONEY PRESIDING.

PRESENT: SENATOR O'MAHONEY OF WYOMING, CHAIRMAN; SENATOR WILLIAM E. BORAH OF IDAHO.

REPRESENTATIVE HATTON W. SUMNERS OF TEXAS, VICE CHAIRMAN; B. CARROLL REECE OF TENNESSEE.

DR. ISADOR LUBIN, COMMISSIONER OF LABOR STATISTICS, REPRESENTING THE DEPARTMENT OF LABOR.

MR. THURMAN W. ARNOLD, ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL, REPRESENTING THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE; WENDELL BERGE, SPECIAL ASSISTANT TO THE ATTORNEY GENERAL.

R. RICHARD C. PATTERSON, JR., ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF COMMERCE, REPRESENTING THE DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE.

MR. EDWIN L. DAVIS, COMMISSIONER, REPRESENTING THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION.

MR.JEROME N. FRANK, COMMISSIONER, REPRESENTING THE SECURITIES & EXCHANGE COMMISSION.

MR. LEON HENDERSON, EXECUTIVE SECRETARY OF THE COMMITTEE.

COUNSEL: H. B. COX (CHIEF COUNSEL); ERNEST MEYERS, JOSEPH BORKIN, BENEDICT COTTONE, DAVID CLARKE, and CHARLES L. TERRELL.

The CHAIRMAN. The committee will please come to order. Mr. Arnold, you have further proceedings to take place this morning?

Mr. ARNOLD. Yes, Mr. Chairman. I will introduce Mr. Cox to make a statement.

Mr. COX. Mr. Chairman and Members of the Committee: This morning the Department of Justice begins the presentation of material relating to the use of patents in the glass container industry. The patents involved cover machinery used to manufacture glass containers; the material presented is intended to disclose the relationship existing between those patents and competitive conditions in the industry.

ANTITRUST LAWS

It is important at the outset to emphasize the purpose for which this presentation is made. The Department has selected this material for presentation because it believes that the material throws light on problems which arise in connection with the enforcement of the anti-trust laws.

The public policy embodied in those laws rests on the assumption that the maintenance of a free and open market in which neither production nor price is subject to artificial limitations or control is socially and economically desirable. The patent privilege is a limited exception to that policy.

To the extent that the Department of Justice is interested in the patent law, its interest is confined to the question of the relationship between patent practices and the free and open market which it is the purpose of the anti-trust laws to maintain.

THE PATENT ISSUE

The Department is not concerned with the patent law as such or with the details of its administration. What is a good patent law, whether the present patent law fulfills its constitutional purpose, and what changes with a view to improvement could be made in its substantive or procedural provisions are questions with which this Department has no direct concern.

The Department asks that the committee in hearing this testimony bear in mind that there are two separate and distinct questions:

(1) Is the present patent law equitable and effective merely as a patent law? and

(2) What is the relation between the patent law and the enforcement of the antitrust laws?

It is the second question in which the Department is interested and it is to the second question that this hearing is addressed.

From time to time during the course of the hearing certain evidence may be adduced with respect to certain practices in connection with the administration of the patent law. In each instance, however, the Department presents this evidence because it believes that a direct and substantial relationship exists between the practice described and the enforcement of the antitrust laws. It does not present this evidence to criticize particular details of the patent law or its administration or with a view to suggesting at this time any changes in its provisions.

At this point in its presentation of material the Department takes no position with respect to the legality or the economic desirability of the practices which will be revealed by the testimony. Its only purpose now is to present the facts with respect to an industry in which patents are of the utmost importance and in which the restrictive use of these patents has had a substantial effect upon competitive conditions.

Two more matters, I think, should be briefly adverted to before the presentation of testimony begins.

The CHAIRMAN. May I interrupt you, Mr. Cox, to ask if I am correct in understanding the statement which you have just made to mean that the presentation of any evidence or testimony this morning does not necessarily mean that the Department of Justice believes that any of the practices which will be revealed involved a violation of the antitrust laws?

Mr. COX. I would not go that far. I would say that in presenting the testimony we are not taking any position in this hearing as to the legality. What opinion the Department might have in the course of the administration of its regular duties is quite another matter which I should prefer not to comment on now, with your permission.

The only point I make there is that we will not regard this hearing as being held for the purpose of trying violations of the antitrust law. If the Department believes those laws are being violated, it will try that condition somewhere else, is the point I wish to make.

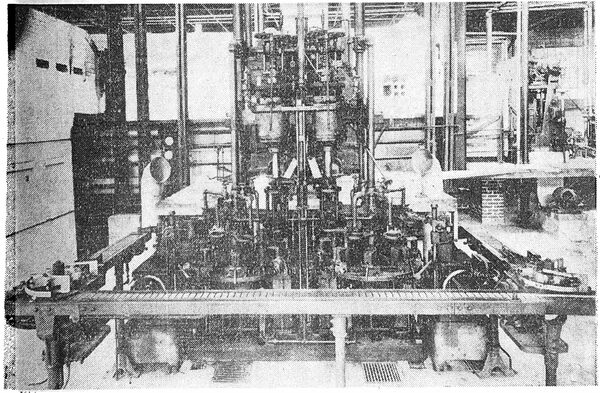

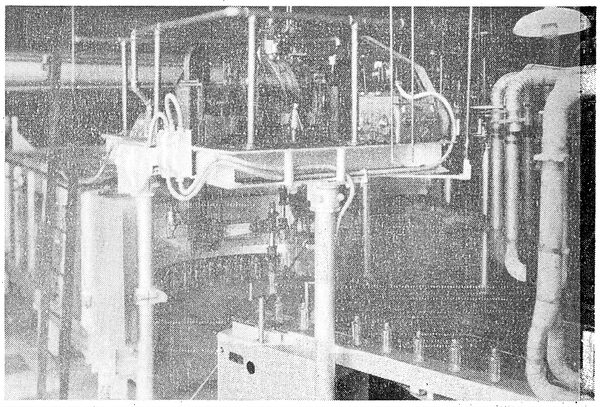

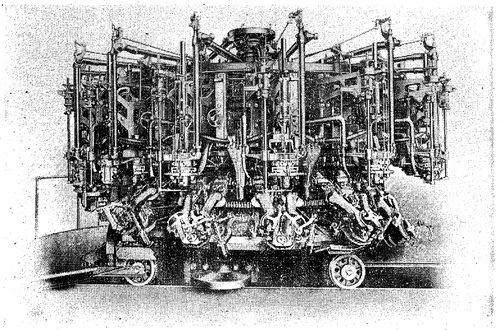

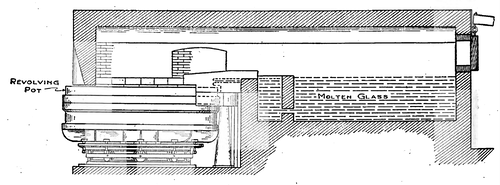

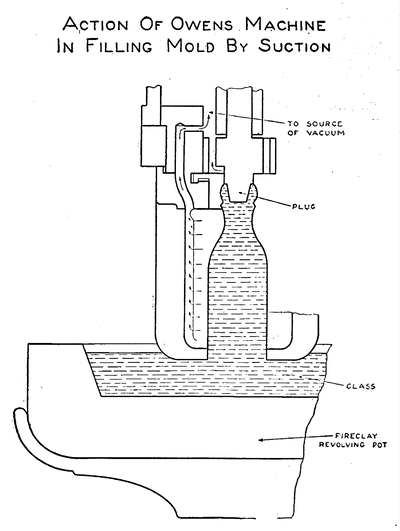

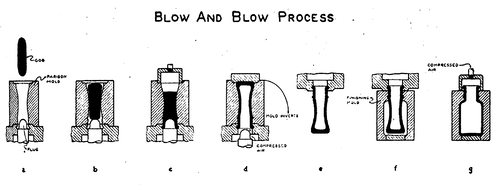

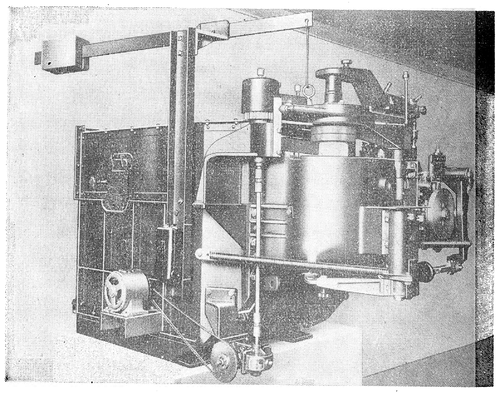

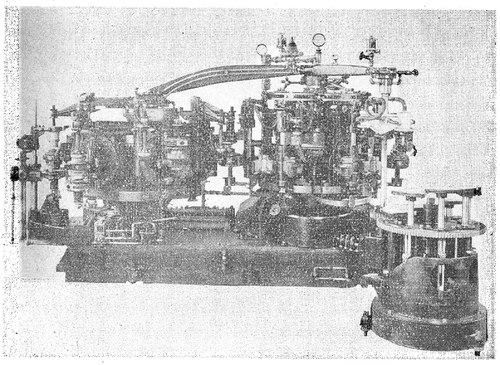

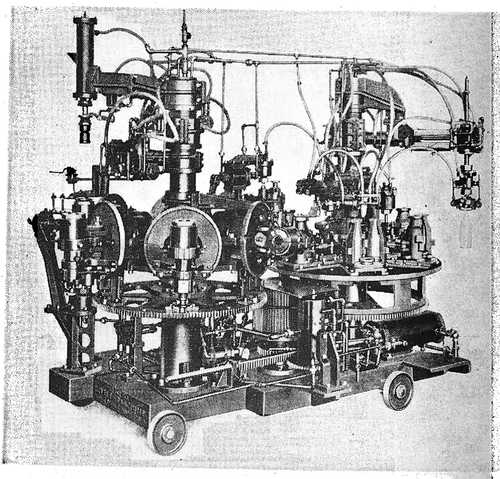

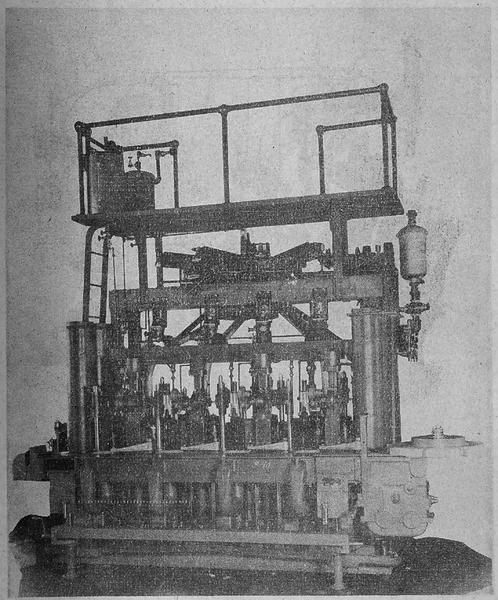

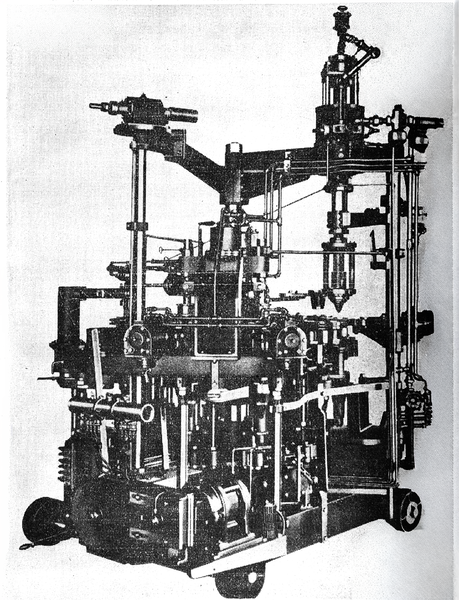

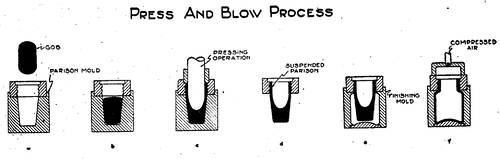

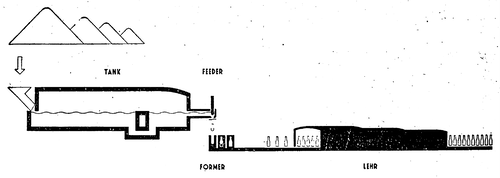

"MANUFACTURE OF BOTTLES"

There are two other matters to which I wish to refer. From time to time, with regularity throughout the testimony, it is going to be necessary to refer to machines and certain technical processes used in the manufacture of glass. In the hope that it might make it possible for the committee and others to follow the testimony the Department has prepared this small pamphlet, entitled "The Manufacture of Bottles." It contains a brief description of the processes used in manufacturing glass, and certain figures and pictures which illustrate those processes. As the testimony develops, I shall try at appropriate times to refer to passages in the booklet which will make clear the testimony which is being given.

"GLASS CONTAINERS"

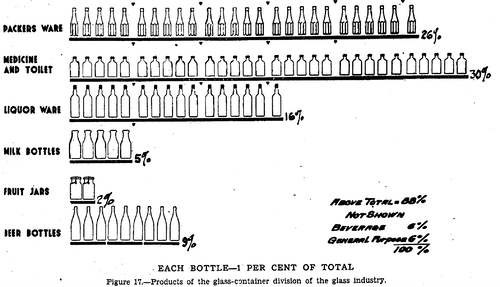

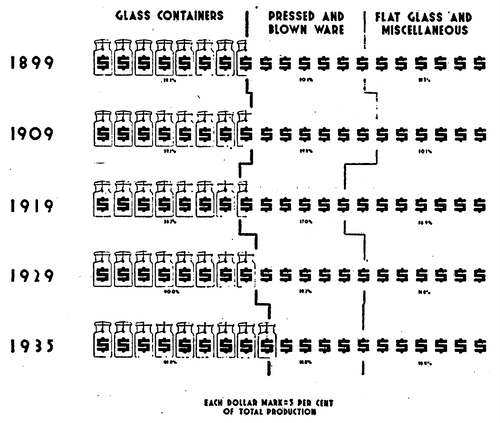

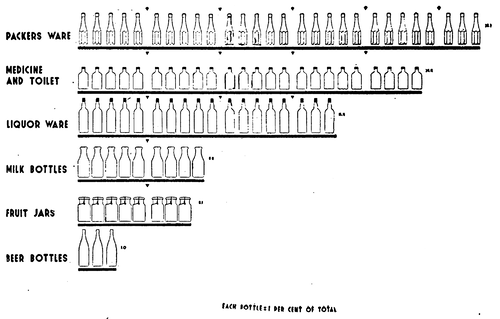

I also wish to make it clear that the testimony which we are going to hear relates to the manufacture of glass containers. It has nothing to do with plate glass or flat glass or window glass. It relates to containers, such as milk bottles, to the jars the housewife preserves fruit in, all the glass containers that food packers pack food in for distribution to the ultimate consumer, and all kinds of bottles.

If that fact is borne in mind, I think it will assist the committee, and others, to follow the testimony.

Mr. ARNOLD. That happens to be the major portion of the glass industry?

Mr. COX. That is correct, yes.

PATENTS AND MONOPOLIES

The CHAIRMAN. It may not be improper for me to remark at this point that, if I understand correctly the attitude of the members of the committee, their interest in the study of patents is primarily one which involves the use of the resources of the country. We are concerned to know whether or not the patent law as it now stands upon the books and the practices which are followed under it by any means restricts the maximum use of our resources.

Senator BORAH. Or tends to establish monopoly.

The CHAIRMAN. Or tends to establish monopoly. Right you are. You may proceed.

Mr. COX. The first witnesses will be Mr. F. Goodwin Smith and Mr. A. T. Safford. While we are waiting, I should like to have this book put into the record if I may.

The CHAIRMAN. If you desire; without objection, it is so ordered.

(The book referred to was received

in evidence and marked

"Exhibit No. 112" and is included

in the appendix of this issue)

The CHAIRMAN. Will the witnesses please be sworn? Do you solemnly swear that the testimony that you are about to give in this proceeding shall be the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, so help you God?

Mr. SMITH. I do.

Mr. SAFFORD. I do.

TESTIMONY OF F. GOODWIN SMITH, PRESIDENT, HARTFORD EMPIRE COMPANY, HARTFORD, CONN.,

AND

A. T. SAFFORD, JR., SECRETARY AND COUNSEL, HARTFORD EMPIRE COMPANY, HARTFORD, CONN.

Mr. COX. Will you give the reporter your full name and address?

Mr. SMITH. F. Goodwin Smith, president, Hartford Empire Company, Hartford, Connecticut.

Mr. SAFFORD. Arthur T. Safford, Jr., Hartford, Conn.

Mr. COX. Mr. Smith, you are at present a member and director of the executive committee of the Hartford Empire Company?

Mr. SMITH. That is correct.

Mr. COX. Mr. Safford, you are the secretary of the company?

Mr. SAFFORD. That is correct.

Mr. COX. You are also a member of the bar of the State of Connecticut?

Mr. SAFFORD. That is correct.

Mr. COX. The principal office of the Hartford Empire Company is in Hartford, Connecticut?

Mr. SMITH. That is correct.

Mr. COX. It is a Delaware Corporation?

Mr. SAFFORD. A statutory office.

AUTOMATIC GLASS

MANUFACTURING MACHINES

Mr. COX. Does your company own patents and patent rights on automatic machinery used in the manufacture of glass? Is that correct?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. Can you tell us now how many patents of that kind the company owns today?

Mr. SMITH. Not exactly. I think we own possibly a little over 700. That can be checked.

Mr. COX. You have that figure. It is about 720.

Mr. SMITH. I am told it is 717.

Mr. COX. Do you manufacture any glass making machinery yourself?

Mr. SMITH. We have it built for us.

Mr. COX. You have it manufactured by someone else?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. You don't manufacture any glass containers yourself?

Mr. SMITH. We do not.

Mr. COX. The machinery which you have manufactured for you by someone else you license to others, is that correct?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. Retaining in each case the title to the machinery?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. You never sell any machines at all?

Mr. SMITH. No.

Mr. COX. In connection with those licenses you also perform certain services for your licensees.

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

PATENT ROYALTIES

Mr. COX. Would you say the largest part of the income from your company is derived from license fees and royalties from your patents?

Mr. SMITH. The largest part of our income is derived from royalties.

Mr. COX. That in fact runs as high as upwards of 90 per cent, doesn't it?

Mr. SMITH. I presume somewhere near there. I haven't figured it out exactly.

Mr. COX. How many people do you employ?

Mr. SMITH. About 300 people.

Mr. COX. And you have a plant at Hartford?

Mr. SMITH. We have an office, a large engineering office, drawing rooms, a little plant for spare parts, and in addition to that we have a glass plant which is used for research and development and experimentation.

Mr. COX. Just an experimental plant; it produces no glass?

Mr. SMITH. That is all. We develop our ideas and inventions in that plant. We do not sell any glassware.

Mr. COX. Do you have in your papers a copy of your balance sheet as of the end of December, 1937.

Mr. SMITH. Yes.

Mr. COX. You had total assets as of that date of about $11,000,000, is that correct?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. You also had a cash reserve of about $229,000.

Mr. SMITH. Yes, correct.

Mr. COX. Another item just labeled "cash," of seven hundred eleven some odd thousand dollars, is that correct?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

The CHAIRMAN. May I interrupt, Mr. Cox. Mr. Smith, the acoustics in this room are abominable. If you can find it convenient to talk a little bit louder, I am sure the persons who are gathered here will hear more readily.

Mr. SMITH. I will be very glad to do so.

The CHAIRMAN. This is particularly asked on behalf of the newspaper men.

Mr. COX. Taking the machines that are involved in the automatic manufacture of glass, Mr. Smith, it is true, isn't it, that those machines, speaking generally, are the furnace, the feeding machine, the kneading machine and an annealing oven?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. Does your company hold patents on all of those machines?

Mr. SMITH. Yes.

EFFECT ON COMPETITION

Mr. COX. Now the automatic feeder, Mr. Smith, is a very important machine so far as the commercial production of glass is concerned.

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. It would be impossible for a man who attempted to perform that process by hand in a plant to compete with one who used an automatic feeder, wouldn't it?

Mr. SMITH. In most lines of ware, the majority lines. There are still hand plants in existence.

Mr. COX. Those are for restricted items, such as expensive perfume and cosmetic bottles.

Mr. SMITH. Yes.

Mr. COX. As far as the great mass of glass containers is concerned, that kind of competition isn't possible.

Mr. SMITH. As far as the great mass of containers is concerned, they are made automatically by different processes.

Mr. COX. And your company, as you said a moment ago, holds patents on machines for the automatic feeding of glass.

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

PATENT MONOPOLY

Mr. COX. And now isn't it true, Mr. Smith, that so far as those machines and those patents are concerned, your company has virtually a monopoly on the patents which relate to that process?

Mr. SMITH. As far as those particular types are concerned, which are owned and developed, we have a monopoly as regards that particular type of machine. That is the monopoly which is given to us by the patent.

Mr. COX. In the first place, I would like to know a little more definitely what you mean by a particular type. Do you mean simply the so-called plunger feeder, or do you mean the gob feeder generally as distinguished from the suction feeder?

GLASSWARE PRODUCTION

Mr. SMITH. There are two economical means of producing glassware, which are the most economical. There are other means of producing glassware. There is the Owens suction machine which is an entirely different method from what Hartford developed, and there is the Hartford machine which is generally known or called a plunger feeder, and represents a method of gob feeding.

Mr. COX. So far as that plunger feeder is concerned, or in fact any kind of a feeder whose principle consists of having glass flow through an orifice and then being severed in suspension, your company has a monopoly, has it not, Mr. Smith?

Mr. SMITH. Well, we think we have covered by patents the particular devices which we license and lease. There are other old methods, screen feeding, and things of that sort, which we feel are not as economical as our methods. They can be generally used as seen fit by various people if they want to use them.

Mr. COX. Some of your patents would even cover the old stream-feed methods in some respects, wouldn't they?

Mr. SMITH. That I wouldn't know.

Mr. COX. I will develop that point later. Taking for a moment that stream-feed method of producing glass, there is only a limited kind of ware that that, could be used for, isn't that true, Mr. Smith?

Mr. SMITH. I wouldn't feel qualified to say.

Mr. COX. You feel you can't express an opinion.

Mr. SMITH. I would say it is not as good as our method.

Mr. COX. Except for the stream-feed method of feeding glass and the Owens suction method, can you think of any method on which your company doesn't have a patent?

Mr. SMITH. No, no known method that we are aware of.

PATENT LICENSES

Mr. COX. Of course you know, don't you, Mr. Smith, that the Owens Illinois Company, which has the patents on the suction method of feeding glass, has not been granted any new licenses since 1914?

Mr. SMITH. I wouldn't know it, no. It may be a fact.

Mr. COX . If I suggest that to you, and then ask this question, isn't it true that if a man wished to go into the business of producing glass and wished to get an automatic feeder, there is only one place in the United States that he can go to get that feeder, and that is your company, would you answer me in the affirmative?

Mr. SMITH. If he wanted to go into business and use gob feeding as a method for producing his ware, he would probably come to Hartford.

Mr. COX. He would have to come to you?

Mr. SMITH. If he wanted to use gob-feeding.

Mr. COX. The only other thing he could use really would be the suction method.

Mr. SMITH. He could go to the Owens Company and ask for a license.

Mr. COX. He would have to go to you or Owens?

Mr. SMITH. Or he could use the old methods or buy his way into the industry by picking up some plant that had a license.

Mr. COX. I am speaking about a man who doesn't want to buy his way into the industry but wishes to start himself with new capital and new plants.

Mr. SMITH. If he wanted to use our equipment he would have to come to us.

Mr. COX. He would have to get your equipment, wouldn't he, or the equipment of the Owens Company?

Mr. SMITH. If he wanted to use our process.

Mr. COX. If he wanted to use any process. There are only two that are available.

Mr. SMITH. Only two that are the most economical.

Mr. COX. And the reason you qualify that is because you have in mind the old stream feed, is that right?

Mr. SMITH. Right.

Mr. COX. So if I could demonstrate to you presently that some certain of your patents cover the stream feed, at least so far as it is now commercially practical to operate, that demonstration would leave us in a position where a man would have to come either to you or to Owens-Illinois if he wished to go into the business of producing glass. Mr. Smith. If that was demonstrated, yes, unless he produced glass by the hand method.

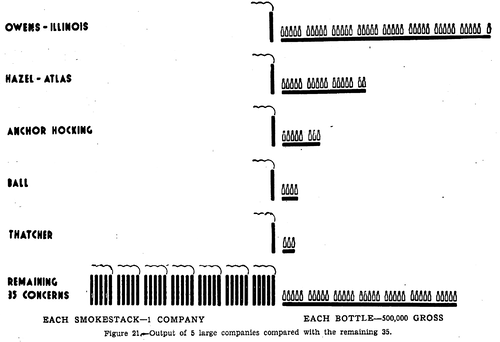

Mr. COX. Of course, if he were going to produce glass by hand he couldn't compete with anybody else producing it automatically. Can you tell us how much of the percentage of the total production of glass containers in this country your company licenses?

Mr. SMITH. About 66, 65 or 67 percent.

PRODUCTION OF GLASS CONTAINERS

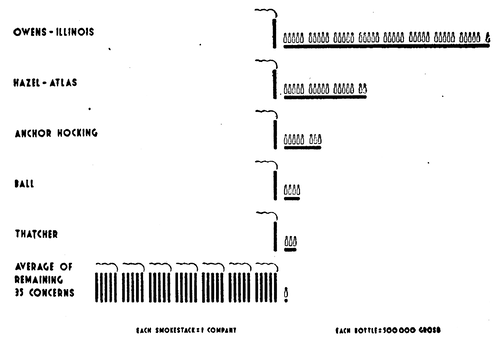

Mr. COX. I show you a sheet, rather the photostatic copy of a sheet, which was taken from your file headed "Memorandum to F. G. Smith, from Survey Statistical Department," and I point out to you that on that sheet the figures indicate that in 1937 your company licensed 67.4 per cent of all the glass containers produced in the industry. Do you believe that is correct?

Mr. SMITH. That is substantially correct.

Mr. COX. I also point out to you the same sheet shows that Owens, Illinois, produced in 1937 suction feeders 29.2 percent of all glass containers produced in the country.

Mr. SMITH. Owens suction here is 21 —

Mr. COX (interposing). I think you have that wrong.

Mr. SMITH. 29.2?

Mr. COX. That is correct?

Mr. SMITH. As far as I know.

Mr. COX. You are satisfied with the substantial accuracy of the figures?

Mr. SMITH. Yes, substantially correct.

Mr. COX. So that less than 3 per cent of the glass containers that are produced were produced in this country in 1937 by someone who is not a licensee of yourself or not a part of the organization of Owens, Illinois?

Mr. SMITH. I think it is around 2 something. Generally speaking, that is correct.

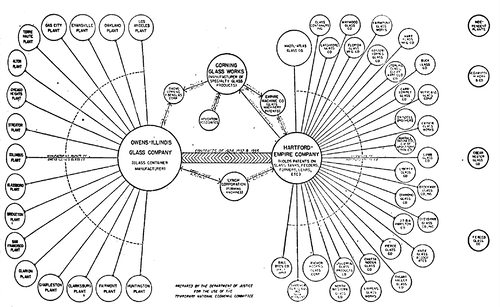

INTER-COMPANY RELATIONS

Mr. COX. I will now hand you and Mr. Safford copies of the chart which the Department has prepared, labeled "Major Inter-company Relations in the Glass Container Industry," I call your attention first to the three small circles on the extreme right, the first one marked "Alexander Kerr," the second "Obear-Nester Glass Company," and the third, "F. E. Reed Glass Company." Now I ask you if it isn't a fact that not one of those three companies is a licensee of the Hartford Empire?

Mr. SMITH. That is correct. We wish they were.

Mr. COX. But they are not?

Mr. SMITH. They are not.

Mr. COX. Can you tell us now whether there is any other company aside from the subsidiaries — I will withdraw that for the present.

I now call your attention to the companies which are shown at the end of the lines radiating from the Hartford Empire Company, and I ask you to glance over those and tell me if it is true that those companies are all licensees of your company. Perhaps Mr. Safford might do that.

Mr. SMITH. I assume you have the list.

Mr. COX. I assure you that is correct, they are licensees of your company. Now I ask you, Mr. Smith, whether there is any other company, aside from the subsidiaries of Owens, Illinois, which stand in a different category, besides the three companies on the extreme right, which is not a licensee of your company, that produces glass containers?

Mr. SMITH. I can't think of any other companies right now.

"INDEPENDENT" PRODUCERS

Mr. COX. You can't think of any others now, so that if we use the word "independent" company as meaning a company which is not a part of Owens, Illinois, or not licensed by Hartford Empire, to your knowledge there are only three such independent companies producing glass containers in the United States today?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. I call your attention to the fact that this chart also shows 40 per cent of the stock of the Hartford Empire Company is owned by the Hartford Machine Company. Is that correct?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. And that your company has a cross-license agreement with the Lynch Corporation?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. And also the Owens, Illinois, Corporation?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. Mr. Chairman, I should like to have this chart introduced in evidence now. I am aware that all of the relationships shown on the chart have not yet been proved, but I ask you to take it subject to proof, which I shall do later on. I should like to have it in. I think it would be convenient as a matter of record.

Representative SUMNERS. May I ask this question? Can't you stipulate without going into detail?

Mr. COX. The point is that these gentlemen are not at the moment probably able to testify or even to stipulate everything that is shown on there.

The CHAIRMAN. This chart was prepared by the Department of Justice from information secured from all of these companies, and particularly from the company represented by the witness here today?

Mr. COX. That is correct, and the other companies. Some of the things shown on the chart relate to the relationships between other companies and the industry, but it is correct to the best of our knowledge and belief, and I have no doubt we shall be able to establish it.

The CHAIRMAN. Unless there is some objection on the part of some member of the committee, the chart may be admitted. (The chart referred to was received in evidence and marked "Exhibit No. 113" and is printed on page 197).

Mr. COX. Of course, as far as particular lines of ware is concerned, Mr. Smith, it is true, isn't it, that your company licenses far more than merely 67 per cent of all production in this country?

Mr. SMITH. I don't know as I understand your question, Mr. Cox.

MILK BOTTLES; FRUIT JARS

Mr. COX. Take milk bottles, for example, what percentage of all the milk bottles produced in this country in a given year would you say are licensed by Hartford Empire?

Mr. SMITH. I would say most all of them.

Mr. COX. Practically all of the milk bottles are produced under license of Hartford Empire? What about fruit jars?

Mr. SMITH. There would be three companies making fruit jars.

Mr. COX. Would you say that an estimate of about 80 and 85 per cent of all the fruit jars in the country were produced under license by Hartford Empire?

Mr. SMITH. Somewhere near there.

Mr. COX. Somewhere in that neighborhood.

Now, packers' ware. For the information of the Committee, packers' ware includes all the kinds of jars that food products are packed in. That is correct, isn't it?

Mr. SMITH. Yes.

Mr. SMITH (interposing). That wouldn't know. I haven't looked it up.

PURPOSE OF PATENTS

Mr. COX. You testified a little while ago as to the number of your patents, Mr. Smith. I should like to ask you some questions as to the purpose of your company in taking out patents.

Representative SUMNERS. Mr. Cox, before you leave that do you purpose to develop at any time during the examination from any other witnesses as to how many of these different licensees are competing amongst themselves in the production of various particular sources of glassware? You have, for instance, I notice, the Ball Brothers fruit jars, and then a number of others. Are all these licensees licensed to produce any sort of glassware which they may want to produce, or are they licensed to produce particular sorts of glassware.

Mr. COX. They are not licensed to produce any sort of glassware they want to.

Representative SUMNERS. I don't want to interfere with your examination, but as one individual member of the Committee I wanted to go into that.

Mr. COX. I planned to go into it. I will do it now, if you prefer.

Representative SUMNERS. Not at all, sir.

Mr. COX. What would you say was the primary purpose of your company in taking out patents, Mr. Smith?

Mr. SMITH. To protect our inventions so that when our equipment comes into public use and somebody tries to copy or pirate or infringe it, we will have the right to go before the court to defend our rights.

Mr. COX. Now, to be sure that I understand that answer, you mean by that, do you, that you take out patents so that you can license or use the machines which your own patents cover without fear of infringement suits?

Mr. SMITH. To protect our invention.

Mr. COX. Is that the only purpose you have in taking out patents, Mr. Smith?

Mr. SMITH. 1 don't know of any other purpose, unless at times we will feel that in the future the trend of an industry may go this way or that way, and somebody comes along with an idea that may affect our future, if we think it is worth patenting it, we patent it.

Mr. COX. Those two statements are your considered answer to my question, are they, Mr. Smith?

Mr. SMITH. It is what I believe.

Mr. COX. Now, Mr. Smith, I am going to hand you a photostatic copy of a document dated February 18, 1930, which was removed from your files, and I am going to ask you if you know who prepared that document. It is not signed.

Mr. SMITH. I think that memorandum was written by Mr. Herbert Knox Smith.

Mr. COX. Will you tell us briefly who Mr. Herbert Knox Smith was?

Mr. SMITH. Herbert Knox Smith for a number of years was here in Washington, a Commissioner in the Department of Commerce, I think — Commissioner of Corporations. He then returned to Hartford and joined our organization and handled our legal matters outside of patent matters.

Mr. COX. How long was he connected with the corporation?

Mr. SMITH. At first, in the early days, I think it was probably around '18 or '17, I have forgotten exactly, he gave us part of his time, and as the company commenced to grow he gave it practically all of his time.

Mr. COX. He was very active in the company's affairs, then?

Mr. SMITH. As regards our legal matters, yes, very.

Mr. COX. And have a voice in determining the company's policy sometimes?

Mr. SMITH. Yes.

PATENTS ON MACHINES

Mr. COX. Mr. Smith, I am now going to call your attention to a statement contained on page 17 of this memorandum, if you will find page 17. The heading there is, "The Main Purpose In Securing Patents." Do you see that, Mr. Smith?

Mr. SMITH. Yes.

Mr. COX. It then reads as follows: "In taking out patents we have three main purposes: (a), to cover the actual machines which we are putting out, to prevent duplication of them." Stopping there, that, as I understood it, was the answer you gave a moment ago. It then goes on to say, "The great bulk of our income results from patents, being a feeder protected by patents," and so forth. I am not going to read that at the moment. Now I call your attention to (b , which is the second main purpose stated in securing patents: "To block the development of machines which might be constructed by others for the same purpose as our machines, using alternative means.

I would like to ask you exactly what you meant by that.

Mr. SAFFORD. That is not Mr. Goodwin Smith's testimony.

Mr. COX. I am aware of that, but I assume the memorandum is an accurate statement of the company's policy.

Mr. SMITH. I don't happen to remember the memorandum. I don't know that was considered, but I think I can answer your question.

Mr. COX. I would like to straighten one up this thing. This may be Mr. Smith's out.

Mr. GOODRICH (of counsel for witness). He doesn't need an out.

Mr. COX. Is it your policy to take out patents to block the development of machines which might be constructed for the same purpose as your machines?

Mr. SMITH. Only in so far as to protect our own machines.

Mr. COX. There is no qualification of that kind in that memorandum, is there?

(Exhibit No. 113)

MAJOR INTER-COMPANY RELATIONS IN THE GLASS CONTAINER INDUSTRY

|

This chart indicates the more important relationships in the glass container industry. The circles on the left side of the chart represent the plants of Owens-Illinois Glass Co., the largest manufacturer of glass containers. This company has an agreement with Hartford-Empire Co., expressed in successive cross-license contracts of 1924, 1932, and 1935. The circles on the right side of the chart represent other companies manufacturing glass containers which are licensees of Hartford-Empire Co. Those on the extreme right represent manufacturers of glass containers who are not licensees of Hartford-Empire Co.

The circle in the upper center of the chart represents Houghton Associates, Inc., a holding company owning 40 per cent of the stock of Corning Glass Works, which manufactures specialty glass products under license from Hartford-Empire Co. Stockholders of Corning Glass Works own 90 per cent of the stock of the Empire Machine Co., a holding company for glass-machinery patents, which in turn owns 40 per cent of the stock of the Hartford-Empire Co. The latter licenses Corning Glass Works as well as some 30 glass-container manufacturers, under its extensive glass-machinery patents. Corning Glass Works and Owens-Illinois Glass Co. each own a one-half interest in Fiber-glass Corporation, a company recently organized to develop glass wool. In the lower center of the chart is a circle representing Lynch Corporation, the largest manufacturer of glass-forming machinery. It has a cross-license agreement with both Hartford-Empire Co. and Owens-Illinois Glass Co.

Owens-Illinois Glass Co. and the other licensees of Hartford-Empire Co. manufacture approximately 96 per cent of all glass containers produced in the United States, while the independents indicated on the extreme right of the chart produce about 4 per cent of the total.

LOCATION OF THE COMPANIES ON THE CHART

Anchor-Hocking Glass Corp., Lancaster, Ohio.

(Anchor Cap & Closure Co., Long Island City, N. Y.).

(Capstan Glass Co., Connellsville, Pa.).

(General Glass Corp., Lancaster, Ohio.).

(Hocking Glass Corp., Lancaster, Ohio.).

(Salem Glass Works, Salem, N. J.).

Ball Brothers Co., Muncie, Indiana.

(Three Rivers Glass Co., Three Rivers, Tex.).

Brockway Glass Co., Inc., Brockway, Pennsylvania.

Buck Glass Co., Baltimore, Maryland.

Capstan Glass Co., Connellsville, Pennsylvania.

(Now part of Anchor-Hocking Glass Corp.).

Carr-Lowrey Glass Company, Baltimore, Maryland.

Chattanooga Glass Co., Chattanooga, Tenn.

Connelly Glass Co., Caney, Kan. (idle).

Corning Glass Works, Corning, N. Y.

Diamond Glass Company, Royersford, Penn.

Fairmont Glass Works, Indianapolis, Ind.

Florida Glass Mfg. Co., Jacksonville, Fla.

Foster-Forbes Glass Co., Marion, Ind.

Gayner Glass Works, Salem, New Jersey.

General Glass Corp., Lancaster, Ohio.

(Now part of Anchor-Hocking Glass Corp.).

Glass Containers, Inc., Los Angeles, California.

Glenshaw Glass Co., Inc., Glenshaw, Pennsylvania.

J. T. & A. Hamilton Co., Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Hart Glass Mfg. Co., Dunkirk, Indiana.

Hartford-Empire Company, Hartford, Connecticut.

Hazel-Atlas Glass Co., Wheeling, W. Va.

Hocking Glass Co., Lancaster, Ohio.

(Now part of Anchor-Hocking Glass Corp.).

Alexander H. Kerr & Co., Huntington,West Virginia, Sand Springs, Oklahoma.

Knape-Coleman Glass Co., Santa Anna, Texas.

(Now part of Liberty Glass Co., Sapulpa, Okla.)

Knox Glass Associates, Inc., Oil City, Pennsylvania.

(Knox Glass Bottle Co., Knox, Pa.)

(Knox Glass Bottle Co. of Miss., Pearl City, Miss., Jackson, Miss.)

(Marienville Glass Co., Marienville, Pa.).

(Metro Glass Bottle Co., Jersey City, N. J.).

(Oil City Glass Bottle Co., Oil City, Pa.)

(Pennsylvania Bottle Co., Sheffield, Pa.)

(Wightman Bottle & Glass Mfg. Co., Parkers Landing, Pa.)

Lamb Glass Co., Mt. Vernon, Ohio.

Latchford Glass Co., Los Angeles, California.

Laurens Glass Works, Laurens, South Carolina.

Liberty Glass Co., Sapulpa, Oklahoma.

Lynch Corporation, Anderson, Indiana.

Maryland Glass Corp., Baltimore, Maryland.

Maywood Glass Co., Los Angeles, California.

Northwestern Glass Co., Seattle, Washington.

Obear-Nester Glass Co., East St. Louis, Illinois.

Owens-Illinois Glass Co., Toledo, Ohio.

Location of plants:

Alton, Illinois.

Bridgeton, New Jersey.

Charleston, W. Va.

Chicago Heights, Ill.

Clarion, Pennsylvania.

Clarksburg, W. Va.

Columbus, Ohio.

Evansville, Indiana.

Fairmont, W. Va.

Gas City , Indiana.

Glassboro, New Jersey.

Huntington, W. Va.

Los Angeles, Calif.

Oakland, Calif.

San Francisco, Calif.

Streator, Illinois.

Terre Haute, Indiana.

Pierce Glass Co., Port Allegany, Pennsylvania.

F. E. Reed Glass Co., Rochester, NewYork.

Salem Glass Works, Salem, New Jersey.

(Now part of Anchor-Hocking GlasCorp., Lancaster, Ohio.)

Sterling Glass (Division of The Warfield Co.), Lapel, Indiana.

Swindell Brothers. Baltimore, Maryland.

Thatcher Manufacturing Co., Elmira, New York.

Three Rivers Glass Co., Three Rivers Texas.

(Now part of the Ball Brothers, Muncie Ind.)

Tygart Valley Glass Co., Washington Pennsylvania.

Universal Glass Products Co., Parkersburg, West Virginia.

Whitall-Tatum Co., Millville, New Jersey

(Now a division of Armstrong Cork Co., Lancaster, Pa.)

Mr. SMITH. Not as it reads.

Mr. COX. You mean you only take out a patent to block the development of some other patent when you are afraid somebody else is going to sue you?

Mr. SMITH. No; I am not cognizant of any such purposes or any such means. If we think that a new idea might be developed over a course of the year by someone else, and we think that idea may affect our machinery and our licensee, we may from time to time try to protect that idea.

Mr. COX. Regardless of whether you intend to commercially apply the idea yourself or not?

Mr. SMITH. You can never tell when you are going to commercially employ ideas. The scene shifts every year or two or three years. Let me give you an example. Today we are spending quite a lot of money on a research development which will be partially and quite well covered by a patent which was taken out in1934. At that time we thought it might have some possibilities; then all of a sudden, in 1937, something transpires that makes that patent a very valuable patent, we hope, one that will be of great benefit to the trade at large when it is put in a process form. You just can't tell when a thing is going to be good and when it is going to be bad. An inventor never knows when or how, or how long it is going to take his invention to be proved of value. It may never be of any value ; it may be of great value. You just can't tell.

PATENTS AS "BLOCKING"?

Mr. COX. When you take out a patent to an invention to block the development of machines which might be constructed by others for the same purpose as yours, using alternative means, isn't it a fact that you are more interested in preventing the use of that device by someone else than you are in using it yourself?

Mr. SMITH. No, I don't think so. So long as I have been with the company I am not conscious of any policy of definitely, deliberately, going out and blocking people. We do take patents out and have a number of additional patents, so that we are protecting and may protect our main development of machinery.

Mr. COX. When you say "protect the main development of machinery" don't you mean to prevent someone else from developing a machine which will accomplish the same purpose, using alternative means?

Mr. SMITH. I don't know if you would say that was wholly so. If we felt that a machine might be improved, we will say, or somebody else might make improvements on our machine, we try to stop and figure out what those improvements might be, and we cover them as soon as we can by patents.

INCOME FROM ROYALTIES

Mr. COX. Of course, about 90 per cent of your company's income is derived from royalties under your licenses.

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. So that anyone who perfects a machine which will accomplish the same purpose that your feeders or other glass machinery accomplish, and obtains a patent on that, is in a position to strike ablow at your income.

Mr. SMITH. He is in a position to possibly affect our income or to affect our licenses.

Mr. COX. He would affect your income, would he not?

Mr. SMITH. If he had a process that was efficient, one that we didn't have, yes. He could naturally do business. There is no market on ideas and inventions.

Mr. COX. And of course you are interested in preventing that kind of result, aren't you.

Mr. SMITH. Yes, normally interested naturally.

Mr. COX. And is that one of the reasons why you take out patents on devices you don't intend to put into commercial operation.

Mr. SMITH. I wouldn't say that was so, Mr. Cox. You had better ask our patent attorneys. It is a very difficult thing for me to answer your question "yes" or "no." We naturally have a big investment in our equipment. We spent a lot of money in developing it. We are looking for a return on that investment. As we put that out, if one of our engineers should come to us and say, "Well, now, here is something that might help," or if somebody else thought of this idea first it might cost us some money, naturally we file an application on that and hope to get a patent.

The CHAIRMAN. You maintain a research bureau?

Mr. SMITH. We do.

DEVELOPMENT COSTS

The CHAIRMAN. For the purpose of keeping abreast or perhaps a little ahead of the procession [sic] procession.

Mr. SMITH. And at all times being in a position to give our licensees the most efficient equipment, because otherwise they would go out of business.

The CHAIRMAN. But so far as you are concerned yourself, your desire is to get the new improvements first and get them patented first.

Mr. SMITH. Then comes a long development process, costing a great deal of money. Naturally we are out to get some return on our money.

The CHAIRMAN. So in order to protect the inventions you now have it is naturally in your interest to secure whatever hold you can upon any competing idea or competing machinery.

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. Not always with a view to using those ideas immediately, Mr. Smith?

Mr. SMITH. Yes and no. Sometimes yes, we do use them; sometimes we don't.

Mr. COX. You would take out a patent if it would protect you against a competing machine even though you didn't intend to use it right away, wouldn't you?

Mr. SMITH. I just don't know.

"AIR FEEDER" PATENTS

Mr. COX. Now, Mr. Smith, let's consider this for a moment. You know, of course, what the difference is between an automatic feeder which works with a vertical reciprocating plunger in the orifice, and one that works by air pressure, don't you?

Mr. SMITH. I know there are those two different types.

Mr. COX. And the Hartford feeder, which you produce , has been a reciprocating plunger feeder?

Mr. SMITH. Primarily so.

Mr. COX. Have you ever caused to be manufactured by you and licensed to anyone any feeders which worked by the air pressure method?

Mr. SMITH. I think we have quite a few licensees who still use the air pressure.

Mr. COX. What I am interested in is whether they got them from you or from someone else.

Mr. SMITH. We didn't build and putout as a standard thing an air feeder, if that answers it.

Mr. COX. You don't do it at all, do you? You don't build and put out, and never have, and licensed it?

Mr. SMITH. Never have built, no.

Mr. COX. All these air feeders your licensees are using now are licensed and bought in the first instance from someone else?

Mr. SMITH. I think, that is correct, substantially.

Mr. COX. Yet you have patents on air feeders.

Mr. SMITH. That is true.

Mr. COX. And you sue people who are using air feeders in their business, even though you have no intention at the present time of developing or commercially supplying an air feeder.

Mr. SMITH. We did develop in the early days an air feeder. I think Mr. Peiler could give you that history. I think it would be quite enlightening for the Committee if they heard how we came into being, and in those early days, as I remember it, Mr. Peiler did develop an air feeder and then chose between the air feeder and the plunger feeder.

Mr. COX. Since that choice you have adhered to the plunger feeder, so far as your own commercial development?

Mr. SMITH. Quite correct.

Mr. COX. Yet you have sued people for infringement on the air feeder. Isn't that a case where you have been using a patent to block the development of machines constructed by others for the same purpose as your machines, which use an alternative method? You have no interest in an air feeder so far as commercial development is concerned?

PROTECTING PATENT RIGHTS

Mr. SMITH. Now, Mr. Cox, I am not a patent attorney. I can give you this picture. If we have patents covering two types of feeders and we choose to say that this type is the better of the two, that is what we license, and I see no reason why, if we have patents covering the other type of feeder, namely the air feeder, we shouldn't take advantage of those patents and protect our rights.

Mr. COX. You mean your rights under the patents, even though you are not using that patent for the purpose of producing feeders and licensing them to others?

Mr. SMITH. Yes.

Mr. COX. You are protecting your rights there really for the purpose of protecting your revenue from your other patents. Is that correct?

Mr. SMITH. Not entirely.

Mr. COX. You know, don't you, and I suppose you have seen it, of the provision in the Constitution which makes it possible for the Federal Government to enact patent laws?

Mr. SMITH. I know there is such a provision.

Mr. COX. Do you know that the tenor of the provision is that Congress shall have power to enact such laws for the purpose of promoting the progress of science and useful arts. You have heard that phrase, "science and useful arts"?

Mr. SMITH. I have.

Mr. COX. Mr. Smith, do you think the use which you make of those patents of yours on air feeders is a use which does promote science and the useful arts?

Mr. SMITH. I would say yes, because they are our original inventions, and I see no reason why, if we choose one type of machine, we still shouldn't protect ourselves on the other.

Mr. COX. Someone else using those machines might develop the machines toa place where they were greatly improved, might he not?

Mr. SMITH. I suppose that might be so.

Mr. COX. Yet you prevent anyone else from attempting or undertaking that kind of enterprise?

Mr. SMITH. No, not deliberately.

Mr. COX. You do if you sue him for infringement and get an injunction.

Mr. SMITH. We sue for infringement because we think people have either copies or are using our rights without legal permission.

Mr. COX. The upshot of that position is this, isn't it, that there is only one person, according to your view, who has aright to use or develop an air feeder, and that is your company, and you are not interested in doing it on a commercial scale.

Mr. SMITH. We would be if we thought the air feeder was more efficient than the plunger feeder.

Mr. COX. You decide that question for the people who want to use the air feeder, don't you?

Mr. SMITH. I don't think so. We have licensed air feeders. I think there are quite a number of feeders operating today that are air feeders.

Mr. COX. I am sure of that, but again I suggest to you that each of those air feeders which you have licensed is a feeder which was manufactured by someone else, licensed or sold outright to a glass manufacturer, and then, by virtue of circumstances which I hope to develop in this hearing, that manufacturer found himself in a position where he had to take a license from you to cover that feeder, even though you have never manufactured the feeder and he had never had any relationship with you before the time he took the license. Those aren't feeders you built yourselves and licensed to the glass manufacturers. I am talking about the things you do yourself.

Mr. SMITH. Now, if that manufacturer infringes on our rights and a court so held, we would give him his choice, and have so done, either to use an air feeder or to use a plunger feeder, whichever he thought was most efficient for his type of business.

Mr. COX. But if he wanted to use the air feeder, he has to pay royalty to you.

Mr. SMITH. Quite right. If he wants to use the air feeder which the courts have said is our property, why then he has to pay royalty to us.

Mr. COX. Now, Mr. Smith, I want to call your attention to the second paragraph, under (b), in this memorandum on page 17, which reads in part as follows: "We have in mind such machines as....." I just want to ask you to look, Mr. Smith, at the feeder name in the first paragraph under (b) on page 17.

Mr. SMITH. Those are all suction machines.

Mr. COX. I call your attention to that because a little while ago you spoke about the stream feeder not being covered by your patents. This suggests to my mind. that perhaps you did take out some patents which covered the improved stream feeder.

Mr. SMITH. I couldn't answer. It might be so and might not.

"FENCING IN" PATENTS

Mr. COX. I now want to call your attention to (c) on the next page of this memorandum, which is the third primary reason stated here. That reads, "To secure patents on possible improvement of competing machines so as to 'fence in' those and prevent their reaching an improved stage."

As I understand that statement, Mr. Smith, and I assume that it represents the policy of your company, it means, in some cases you secure patents on devices which are merely improvements on devices which are covered by patents held by someone else. Is that correct?

Mr. SMITH. That is not a corporate policy.

Mr. COX. Are you repudiating this memorandum, Mr. Smith?

Mr. SMITH. As a corporate policy, or as ever having this memorandum come before the board of directors, or as having been approved as a statement of our entire policy, I am.

Mr. COX. You told us a little while ago Mr. Smith was a man who had been with the company for many years and was active in its affairs. Would he seriously state in his memorandum, "intaking out patents we have three main purposes" when that was not the case?

Mr. SMITH. I don't know how that memorandum was written or why. I do happen to remember that I have seen a copy of it and read it, at the time it was written.

When we come to the question of deliberate policy or setting engineers to work to prevent others from getting certain things, that isn't a corporate policy. There are a great many times when an inventor will come in and say, "Now I have this idea or that idea," and it will encompass part of some other machine and we do file application and get together a patent.

Mr. COX. Then you want us to understand now that when you do that you don't do it for the purpose of fencing in the other man's invention and preventing it from reaching an improved stage?

Mr. SMITH. I don't like the words "fencing in."

Mr. COX. It is not my word, Mr. Smith.

Mr. SMITH. We do that off and on as the occasion arises.

Mr. FRANK. Would you consider it improper for you to adopt the policy indicated in paragraph (c)?

Mr. SMITH. I don't think we would deliberately go out and spend our time and money in a fencing in policy.

Mr. FRANK. My question is not whether you have done so, but whether you would consider it improper to do so.

Mr. SMITH. No, I think you have to protect your large investments; you have to protect your licensees. If you don't protect your licensees, they can't stay in business.

Mr. FRANK. Well, whether that has been your policy or not, you wouldn't consider it improper for your company to adopt such a policy?

Mr. SMITH. No.

Mr. COX. That would be because you think it is necessary to protect your licensees?

Mr. SMITH. In so far as that policy protects our investment, protects our licensee, we would say it is all right.

PROTECTION TO LICENSEE

Mr. COX. Just how does that policy protect the licensee?

Mr. SMITH. The licensee looks to us to continually improve the equipment that he is using, to take certain machines and add things to them, to increase his fee, to better his quality, to help in the glass furnace troubles, to enter in and show him how to make bottles at the lowest possible cost, to give him the advantage of what we find in other plants and how they are operating, to at all times keep him in a competitive situation; otherwise, he can't live.

Now, if we saw over in one corner something that we thought was desirable, even though it was going to head off somebody else, and we should be the first to invent that and get a patent on it that is going to assist us by protecting us or help our licensee, we would so do it.

Mr. COX. Isn't it possible, Mr. Smith ,that if you didn't fence in someone else's invention, he might invent a device which your licensee could use?

Mr. SMITH. I suppose that is possible, but I don't think the invention would beat all basic or original.

Mr. COX. Well, it is really not necessary for the protection of your licensees for you to stifle inventions on the part of everyone else.

Mr. SMITH. I am not conscious of the fact that we have a policy that wants to stifle. We have a policy that wants to protect what we are doing and wants to insure our licensees of the best possible means of producing glassware at the lowest cost.

PERIOD OF LICENSES

Mr. ARNOLD. May I get that a little clearer in my own mind, Mr. Smith? Your licenses — I don't know how long they run —

Mr. SMITH (interposing). They run, some of them, eight years, with a renewal, and some of them for the life of the patent.

Mr. ARNOLD. That is contract which your licensee has and which you have against the licensee?

Mr. SMITH. Right.

Mr. ARNOLD. Now, if a new development should occur so that another machine could compete with that machine which you have licensed, then both you and the licensee would be in a disadvantageous position because of that new competition.

Mr. SMITH. Right. We would probably go out of business because the licensee could cancel his contract with us. He could use the new development, the new process, and our income would cease.

Mr. ARNOLD. Therefore, to protect that eight-year-license is not necessarily not because you are anxious to stifle inventions, but to protect your own income it is necessary for you to fence in and stop this new machine from developing. Have I put it too —

Mr. SMITH (interposing). I think you have put it a little too strongly. I think I would say part of it is true, in so far as we protect ourselves, protect our future, and protect our licensee.

The CHAIRMAN. Let me put it this way: You do watch these competing machines, do you not?

Mr. SMITH. Yes, we do.

The CHAIRMAN. And in your research laboratory you study them for the purpose of developing improvements upon them?

Mr. SMITH. Right .

The CHAIRMAN. And if you do develop an improvement upon a competing machine, that thereby enables you to extend your influence, let me say, your contractual relationship, over the competing machine or those who use it. A competitor could not use any of the improvement.

Mr. SMITH. That depends upon what the improvement is, the effect of it ,whether it is incidental, or whether it is major.

EFFECT OF NEW INVENTIONS

The CHAIRMAN. Naturally, it depends upon the importance or unimportance of the improvement. Let us assume that a very valuable improvement has been discovered simultaneously, or thereabouts, by the competing company, which is operating a competing machine, and you likewise developed one about the same time, then a conflict arises immediately, does it not, whether or not that improvement may be used without payment of royalty to you?

Mr. SMITH. Well, what would happen as a practical matter would probably be the stoppage on the part of both of us. The competitor might have 60 per cent of the value of the invention and we might have 40, or vice versa, or some other percentage. Neither of us could go out because he would sue us, and if he went out, we would sue him, so it would probably mean that we cross-license.

The CHAIRMAN. Well, you are engaged in the business of inventing and patenting and you do this for the purpose of collecting license fees and royalties primarily?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

The CHAIRMAN. So you watch the entire industry, and if you can extend the influence by means of invention over competing industries, you are going to do it because it means money to you.

Mr. SMITH. Correct, and also it keeps our licensee in a competitive situation.

The CHAIRMAN. So the incidental effect upon the development of science and arts — it is only an incidental effect so far as you are concerned. Mr. Smith. Perhaps I don't quite understand that question.

The CHAIRMAN. I mean your primary consideration is to make license fees and royalties out of these inventions?

Mr. SMITH. Right.

The CHAIRMAN. And you are willing to suppress the competition for that purpose, to fence it in? Well, I don't want to ask —

Mr. ARNOLD (interposing). Taking what your personal policy is out of this, the total situation illustrated by this picture is one in which whoever sits in your seat is under very strong pressure to protect his licensees by preventing competition in machines from arising, isn't it?

Regardless of who sits there that pressure exists?

Mr. SMITH. I think that generally maybe it.

Mr. FRANK. I would like to make a differentiation —

Senator BORAH (interposing). Let me make a suggestion. I think Mr. Cox ought to be permitted to develop his case.

The CHAIRMAN. The Senator is correct . That has been the policy formerly announced , and we have all been violating it, and we will refrain, Mr. Cox.

Mr. COX. That is quite all right with me. Two or three things have been developed in this which I should like to go into, and particularly Mr. Arnold's last question. Mr. Smith, I am interested in that, because I wonder to just what extent your licensees are interested in preventing the development of a new device even by someone else which would enable them to produce, which could be used to produce glass. Isn't it true that your licensees are all engaged in producing and selling glass containers?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. And let's assume for the moment that their primary interest is in producing and selling glass containers, and that as far as they are concerned, they will use any kind of machinery which will enable them to produce and sell glass containers, good glass containers at a good price, at which they can make a profit if they can get that machinery. Why wouldn't they be as content to get the machine or device from someone else as from you?

Mr. SMITH. You see, Mr. Cox, people that pay us royalties look upon us as the engineering and development and research concern that is going to develop machinery for them, that is going to keep them abreast of the times. They can't afford to spend large sums of money each year in research work, or development work, but they look to Hartford to take part of their royalties and spend money in the development work, glass compositions, anything that affects vitally the whole industry.

Mr. COX. Do you think that part of the royalty money, at least that is paid to you, you take — I don't want to use too strong a word — in sort of a trust to use for development and experimental purposes?

Mr. SMITH. There is no question but that we have a deep sense of obligation to protect our licensees, to keep them in business, to continually reduce their cost and give them the most efficient equipment.

Mr. COX. You feel that is almost a fiduciary responsibility.

Mr. SMITH. No, I don't think it is that, but I think it is just decent business ethics.

Mr. COX. Do you think that they would feel that they hadn't had their money's worth if somebody else would perfect an invention that would enable them to produce glass more efficiently than yourself?

Mr. SMITH. I am quite sure if anybody else came along with an invention or process that was more economical than our process, that our licensees would cancel their contracts with us and install the most efficient process.

Senator BORAH. That would be competition.

Mr. SMITH. You can't help that, Senator. We have no monopoly on brains.

Mr. COX. You have a monopoly on some other things, though.

Well, isn't it a fact, really, Mr. Smith, that the important thing in this picture so far as this "fencing in" is concerned, is 90 per cent of your income which comes from royalties and not the feelings of your licensees?

Mr. SMITH. I couldn't answer that question.

Mr. COX. You feel you can't answer that question.

Mr. SMITH. I don't know what each individual licensee feels. I know that some of them feel that contact with us, the service we give them, is worth more than the royalties they pay. Some others might not.

Mr. COX. I was rather more interested in what you felt than what they felt. I was really inquiring whether in following this policy, your eye wasn't on the 90 percent of your royalties rather than on the feelings of your licensees.

Mr. SMITH. No, I think the sound policy, looking ahead, of any business is based primarily on the fact that you must serve your customers, and if you don't serve them you don't stay in business.

Mr. COX. Well, your customers would have a little difficulty going anywhere else, wouldn't they, Mr. Smith?

Mr. SMITH. Until there is something new comes on the market that is better than what we have.

Mr. COX. There isn't any place for them to go now, that is what I mean?

Mr. SMITH. They can go to suction.

Mr. COX. Well, if they went to suction you would sue them.

Mr. SMITH. I don't know why.

Mr. COX. You are suing some people who are using suction.

Mr. SMITH. Not to my knowledge.

Mr. SAFFORD. What you refer to is not a suction machine.

Mr. COX. I withdraw that. The only place they could get a suction machine would be from Owens.

Mr. SAFFORD. Not necessarily.

Mr. GOODRICH. I think Mr. Parham can give all the details of that.

Mr. COX. Except for the suction machine there is no place for them to go.

Mr. SMITH. Not to get the most modern equipment, or the most efficient.

Mr. PATTERSON, Let me ask, the patents in the suction machine have not expired, have they?

Mr. SMITH. The old original fundamental, basic patents have expired and if you and I wanted to go into business tomorrow we could build a suction machine under those original patents, or just the same kind of machine that was originally covered by those patents.

Mr. COX. It is true, isn't it, Mr. Smith — and perhaps we could get Mr. Parham to answer informally — that the machines now used by Owens, the suction machines, the improved machines, are covered by patents.

Mr. PARHAM. I understand you can build thoroughly good machines, if you happen to know how, under the old patents. That is my understanding.

Mr. COX. Mr. Chairman, I am about to start on a new topic. Is it your practice to adjourn at noon now or do you wish to go on?

The CHAIRMAN. I think probably, unless there is objection, it would be well, if you have finished this line of examination, to take a recess until 2:00 o'clock.

(Whereupon, at 11:55 a. m., a recess was taken until 2 p.m. of the same day.)

The Committee resumed at 2:05 p. m. on the expiration of the recess.

Present in addition to those previously listed:

SENATOR WILLIAM H. KING of Utah; MR. HERMAN OLIPHANT, General Counsel, representing the Department of the Treasury.

The CHAIRMAN. The Committee will please come to order. Are you ready to proceed, Mr. Cox?

Mr. COX. Yes, I am, sir.

The CHAIRMAN. You may, then.

TESTIMONY OF F. GOODWIN SMITH, PRESIDENT, AND OF A. T. SAFFORD, SECRETARY AND COUNSEL, HARTFORD EMPIRE COMPANY, HARTFORD, CONN. — (Resumed).

Mr. COX. Mr. Smith, a few questions about the Hartford Empire Company which I didn't ask this morning I would like to ask now. Will you indicate briefly what the capital set-up of your company is? I mean, what kinds of stock you have outstanding. If you prefer, I will have Mr. Safford do this.

Mr. SMITH. It is common stock, par value.

Mr. COX. Any preferred stock?

Mr. SMITH. None outstanding.

Mr. COX. No bonds?

Mr. SMITH. No.

Mr. COX. Is your stock listed on any of the exchanges?

Mr. SMITH. It is not.

Mr. COX. Is it a widely held stock?

Mr. SMITH. No.

Mr. COX. Do you publish periodically your balance sheet?

Mr. SMITH. We do not.

Mr. COX. Do you file a financial report either in the State of Connecticut with any State authority, or in the State of Delaware with any State authority?

Mr. SAFFORD. Only for tax purposes.

Mr. COX. Can you tell us in a very brief way what kind of statement that is?

Mr. SAFFORD. For Connecticut it is the tax required under their business tax law, and I think it gives the balance sheet and the income statement as sent to the United States Treasury.

Senator KING. I suppose you file the Federal tax report in addition to the ones to the State.

Mr. SAFFORD. Yes, sir.

Mr. COX. Do you know whether you file a similar report in the State of Delaware or not?

Mr. SAFFORD. It is not required.

Mr. COX. Aside from those, whatever may be contained in your return to the State of Connecticut and the return which you file with the Department of Internal Revenue of the Treasury Department here, there is no disclosure of your balance sheet or your income statement. Is that correct?

Mr. SAFFORD. That should be qualified further; that is, in each State where the corporation is qualified to do business there are certain tax reports which you must file.

Mr. COX. Will you tell us in how many States your corporation is qualified to do business.

Mr. SMITH. Seven or eight.

Mr. COX. And in those States you file whatever reports are required to be filed by law?

Mr. SAFFORD. Yes.

Dr. LUBIN. Do any of the States make those reports public?

Mr. SAFFORD. I don't think so, Dr. Lubin.

Mr. COX. No statement with respect to your company is contained in Moody's or Poor's or any of the other financial reports?

Mr. SAFFORD. No, sir.

Senator KING. Do the States treat your reports differently from reports filed by corporations doing business within a State?

Mr. SAFFORD. I think it puts us all in the same category. I think the figures are all confidential with the departments with which they are filed.

Senator KING. Who imposes confidentiality, if you permit that expression?

Mr. SAFFORD. It is under the statutes, sir, of the respective States.

Senator KING. You conform with the State practice and the State officials follow the State requirements?

Mr. SAFFORD. Yes, sir.

Senator KING. So if they are treated as confidential is it at your request or in pursuance of the law which the State officials follow?

Mr. SAFFORD. It is in pursuance of the law which the State officials follow.

PATENT LICENSES

Mr. COX. Now, Mr. Smith, I would like to ask some questions about the licenses under which your patents are used. You said this morning that you had patents on the feeding machines, the forming machines and the lehr or annealing machine, and I assume in the case of each of those machines, when your company licenses under the patent which applies to the machine, you retain title. Is that correct?

Mr. SMITH. That is correct.

Mr. COX. Do you have any patents on glass furnaces?

Mr. SMITH. We have.

Mr. COX. Did you ever license a glass furnace?

Mr. SMITH. We have not as yet.

Senator KING. Have you declined?

Mr. SMITH. No; we haven't the experiments completed.

Mr. COX. So that in the case of a man who licensed from you feeding machines and his forming machines and the lehr or annealing oven, the only part of the machinery used in manufacturing glass which he owns outright is the furnace. Is that right?

Mr. SMITH. In some cases, yes; in some cases, no. We have title to the actual machines we ourselves built and licensed, but in a number of other cases we haven't actual title.

Mr. COX. Even though you have licensed those?

Mr. SMITH. Yes.

Senator KING. And accept royalties?

Mr. COX. That is again a case where the machine is not built in the first instance by your company and licensed?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. In some of those cases where the machine was not in the first instance built by your company you have at a later date acquired title and then licensed it?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Senator KING. You can't become a purchaser of the patent over a licensee of the patent?

Mr. SMITH. I beg your pardon.

Senator KING. Do you become a purchaser of the patent under which the machine was constructed or a licensee of the patentee? Perhaps I didn't make myself clear. I understood there were some machines which you didn't make.

LICENSE FEES VS. ROYALTY CHARGES

Mr. SMITH. Actually build. When the courts decide a suit in our favor, if the manufacturer had infringed and wanted to license, he could either take our own machinery or keep his machinery. In some cases he took our machinery; in other cases he kept his machinery.

Mr. COX. In some cases where he kept his machinery you paid him a certain contribution for the title of the machinery?

Mr. SMITH. Yes.

Mr. COX. In some cases you didn't buy title, you just took a license?

Mr. SMITH. Yes.

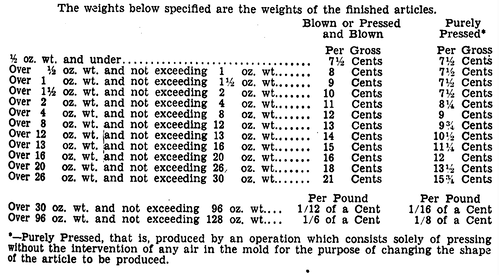

Mr. COX. There are two different kinds of charges you made in connection with the license, are there not, a license fee and a royalty charge?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. The license fee is a lumpsum payment made either at once or in installments which is a contribution to your granting the license?

Mr. SMITH. Yes.

Mr. COX. The royalty fee, on the other hand, is a fee which is paid for the use of the licensed machinery?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. And that royalty fee is on a quantity basis, isn't it?

Mr. SMITH. So much per gross, depending on the sliding scale, depending upon the weight of the article made.

Mr. COX. Now, taking up the license fees, in the first place can you, or Mr. Safford, tell us what the license fee is for the feeding machines?

Mr. SAFFORD. $2,000.

Mr. COX. And how long has it been $2,000?

Mr. SAFFORD. I would say within two or three years.

Mr. COX. Isn't it about 1936 that it changed from $2,500 to $2,000?

Mr. SAFFORD. Yes.

Mr. COX. Can you tell us what the license fee is for forming machines?

Mr. SAFFORD. $8,000 for the four mold-forming machines.

Mr. COX. And what is the license fee for the lehr?

Mr. SAFFORD. $2,500.

Mr. COX. Do you have there a schedule of the royalty fees so we could avoid this? Just put it in.

(The schedule of royalty fees referred to was received in evidence and marked "Exhibit No. 114" and is printed on Page 203.)

Mr. COX. This is on the feeding machine, isn't it?

Mr. SAFFORD. Yes.

Senator KING. What was the answer to the question?

Mr. SAFFORD. Yes.

Mr. COX. If there is no objection, I should like to have this —

The CHAIRMAN (interposing). It maybe admitted.

Mr. COX. Those agreements usually provide for the payment of a minimum royalty fee, don't they?

Mr. SMITH. Yes.

The CHAIRMAN. This is a list of royalty rates and not of license fees?

GROSS ROYALTIES RECEIVED

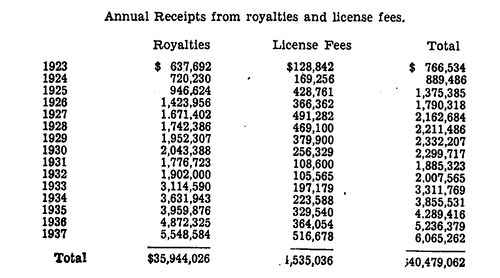

Mr. COX. That is right, As a matter of fact, we have a statement here which has been mimeographed, and which we might offer at this time, subject to check by the witnesses, showing the total gross amount received by way of royalties and license fees by the company for each year since 1923. This is a gross figure and does not represent a net income figure of the company. I would like to offer that subject to correction.

Mr. SMITH. That is all right.

The CHAIRMAN. It is not clear from the colloquy that has been going on at that end of the table whether this has been identified or not.

Mr. COX. It has been identified as having been prepared from statements which were furnished to us by the company, and I am now about to offer it, subject to correction if any arithmetical errors are found.

The CHAIRMAN. This purports to be a statement of receipts from royalties and license fees by the Hartford Empire Company, from and including the year 1923 to 1937, both inclusive?

Mr. COX. That is correct.

The CHAIRMAN. It may be received.

(The statement referred to was received in evidence and marked "Exhibit No. 115" and is printed on Page 203.)

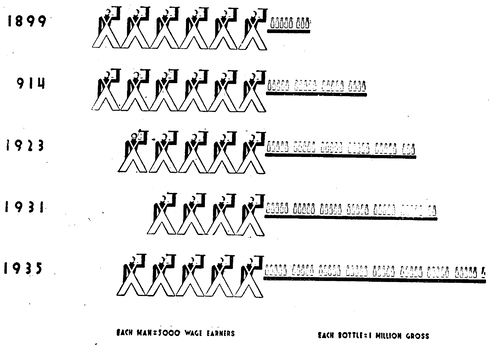

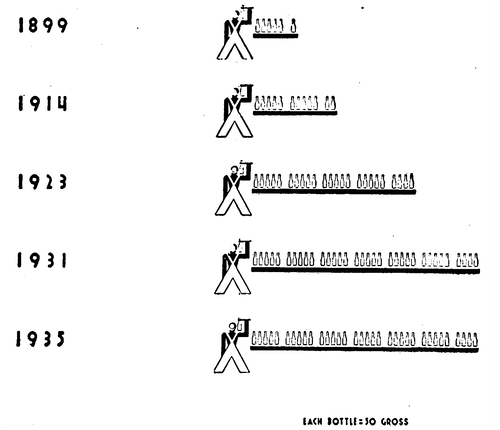

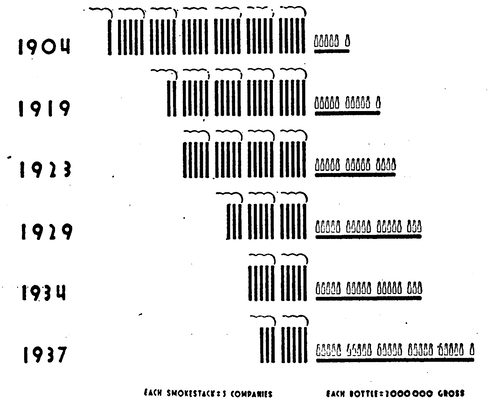

Senator KING. I would like to ask one question. I note that in 1923 the total received from royalties and licensee fees was $766,534; in 1937, $6,065,262. I am interested to ascertain whether or not that large increase in the licenses and in the royalties resulted from an increase in license fees and royalties, or was it an increase in production?

Mr. SMITH. Increase in the number of licensees. In 1923 we had not established our patents; they had not been adjudicated. As our patents were adjudicated and established we took on more licensees each year, so that the royalty return came instead of from fifteen or twenty licensees, from a great many more licensees. All told, I think we had something like eighty-six licensees.

Senator KING. I understood from your testimony that the license fees or royalties were based in part at least upon production.

Mr. SMITH. All the royalties are based upon production.

(Exhibit No. 114)

RATES OF ROYALTY

|

(Exhibit No. 115)

HARTFORD-EMPIRE COMPANY

|

Senator KING. Would any of this increase from $766,000 to $6,065,000 result from increased production?

Mr. SMITH. Oh, yes.

Senator KING. As well as from increased number of licensees and those from whom you were receiving royalties.

Mr. SMITH. Quite right. In some cases we have reduced the royalty rates.

The CHAIRMAN. I merely wanted to call the attention of the members of the committee to the fact that this morning we agreed to follow a rule of procedure which was originally suggested I think by Senator King, namely, that we would permit the Department to proceed with the original examination before asking our own questions.

We are all violating this rule, Senator, but in the interest of orderly procedure it was felt it would be the best way to go along.

Senator King. The Senator's statement is in part accurate but I will not challenge the inaccuracy.

Senator BORAH. Who is going to enforce the rule?

The CHAIRMAN. I shall attempt to ask the members of the committee to refrain.

Mr. COX. While we are dealing with the matter of royalties and license fees, I should like to state that the Department has prepared a computation showing the percentage relationship between royalties and gross license fees, and the total gross income of the company from 1932 to date.

This computation shows that the percentage relationship in 1932 was 91.2 percent; in 1933, 93.6 per cent; in 1934, 96.2 per cent; in 1935, 95.1 per cent; in 1936, 93.7 per cent; 1937, 94.5 per cent.

I am now going to give this computation to the witnesses so that they can check it, and we will make any corrections that may be necessary. I suggest that we do that over the evening, if that is convenient for you.

Mr. SMITH. I would be very glad to, if we could.

LICENSE AGREEMENTS

Mr. COX. You may keep that, and we will make any corrections that are necessary. Now to revert to the license agreements, those license agreements, aside from containing the provision requiring the payment of royalties, contain certain other restrictive provisions, do they not?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. They contain restrictions as to the kind of ware which can be manufactured by the licensed machinery, is that correct?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. Do you have outstanding any license which is absolutely unrestricted so far as the kind of ware which may be manufactured is concerned?

Mr. SMITH. In the container field, I think we have two such licenses, two un-restricted licenses.

Mr. COX. That is, strictly in the glass container field there are two licensees, and only two, who are free to manufacture any kind of ware they please with the licensed machinery.

Mr. SMITH. That is correct.

OWENS-ILLINOIS COMPANY

Mr. COX. Could you tell us who those licensees are?

Mr. SMITH. The Owens-Illinois Glass Company and Hazel-Atlas Glass Company, both of which companies do a national business, have plants located in various parts of the country, and also make, as they advertise, everything in glassware and containers.

Mr. COX. The Owens-Illinois Company is the largest manufacturer of glass containers?

Mr. SMITH. Yes.

Mr. COX. And the Hazel-Atlas Company is another very large manufacturer of glass containers?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. But there is no license, even those licenses, which is absolutely unrestricted as to kind of ware which can be produced by the machines.

Mr. SMITH. I don't get your question?

HAZEL-ATLAS GLASS COMPANY

Mr. COX. Neither the Owens-Illinois Company nor Hazel-Atlas is free under its license to manufacture heat-resisting ware, is that correct?

Mr. SMITH. That is true.

Mr. COX. Or electric bulbs.

Mr. SMITH. That is true.

SPECIALTY WARE

Mr. COX. But those kinds of ware are, of course, not normally regarded as being in the glass container class.

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. And that kind of ware and several others are what is known in the trade as specialty ware.

Mr. SMITH. Specialty ware, and they are not allowed to make specialty ware.

Mr. COX. And you have only one licensee who is allowed to make specialty ware, is that correct?

Mr. SMITH. Practically. You are talking about bulbs or heat-resisting ware. I am told by my partner that is not correct.

Mr. SAFFORD. I think if you apply the term "specialty" to all non-containers, then there are a great many more licensees than one.

Mr. COX. I wasn't applying the term in quite that wide a way, although my question perhaps was open to that kind of interpretation. I have in mind the specific kinds of classifications that are named in the contract between yourselves and the Corning Glass Works: signal and optical ware, electric bulbs, and certain kinds of heat-resisting ware. As to those types of ware, you have only one licensee and that is Corning.

Mr. SMITH. Right.

CORNING GLASS WORKS

Mr. SAFFORD. Except as rights have been released by the Corning Glass Works.

Mr. COX. Except as they have granted sub-licenses. That is a contractual relationship between Corning and others?

Mr. SAFFORD. No, they have permitted us to grant rights in those fields.

Mr. COX. And in some cases you grant those rights with the consent of the Corning Glass Works?

Mr. SAFFORD. That is right.

Mr. COX. To return to the glass container field, you said a moment ago you had only two licensees who are absolutely unrestricted as to types of wares they can produce. Are those two licensees also restricted as to the quantity of the different types of ware that can be produced on the licensed machine?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. But they are the only two who are so unlimited?

Mr. SMITH. Correct.

Mr. COX. All the other licensees are limited as to the amount or the number of glass containers that they can produce.