[Trade Journal]

Publication: Electrical World

New York, NY, United States

vol. XXV, no. 18, p. 541-542, col. 1-2

An Electrical Porcelain Factory

Owing to the difficulty experienced in obtaining in very great quantity porcelain possessing the requisite character for electrical work, the General Electric Company established some time ago a very complete porcelain factory as an integral part of its immense establishment at Schenectady, and this has been in constant operation ever since with excellent results.

This porcelain factory, although only a pottery in miniature, is nevertheless complete as to details, comprising kilns, mixing, moulding, and drying rooms, and a full equipment of the latest and most approved machinery.

| |||

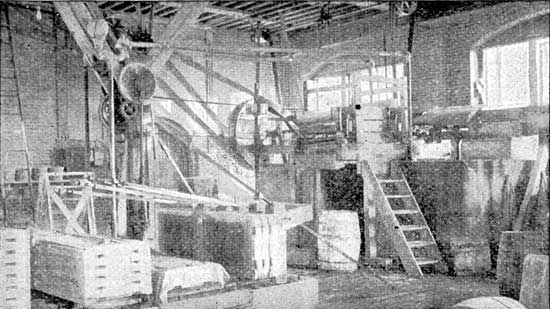

| Mixing Room. |

The building is a two-story brick structure covering an area of about 14,000 square feet. On entering by the main door one is admitted immediately to the mixing room where crude kaolin, or china clay is brought to be washed, manipulated and mixed. After passing through the mixing machine the clay, the clay is strained through bags to remove any hard material which might interfere with the succeeding operations. From the straining press it comes in large lumps, and in that condition is partly dried, placed in a pulverizer and reduced to the necessary condition for use in the press room, to which it is taken in the shape of moist, grayish, disintegrated clay.

| |||

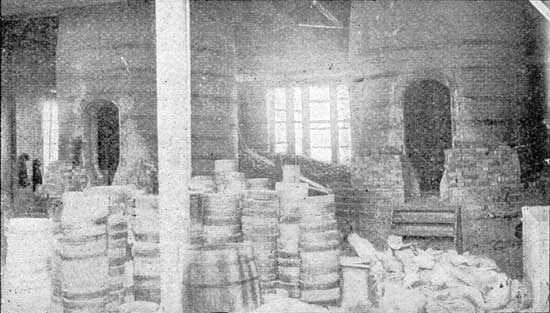

| View of Kilns. |

The press room is immediately over the mixing room. The machines in which the porcelain is moulded are upright screw presses and stand along the three sides of the room directly under large windows. The moulds used are made of special tool steel by a corps of experienced tool makers in the works. In designing these moulds, or dies, the shrinkage of the porcelain due to the drying and pressing is calculated to a nicety, in order that when the porcelain leaves the kilns in its finished state, the metal pieces, which have been punched out in the stamping department, may fit accurately. The catalogue number of each piece of porcelain is cut in the die, so that the number appears in relief on the base of the finished piece. The lower part of the die is fixed to a small table, which can be moved up or down by means of a foot lever and sets in a hollow space in a larger table forming the base of the press. The upper part of the mould is fitted to a sliding bar, which is elevated or depressed by a lever and screw. When the die is fixed in position, the pressman weighs out the proper quantity of pulverized clay to be used. With a small brush the two dies are then thoroughly dampened. The bottom one is then lowered to its normal position, and the operator pours in the clay and presses it down evenly with his hands to give it a preliminary packing. A vigorous twist given to the lever brings the upper die down upon the clay with considerable pressure; another twist in the opposite direction raises the upper mould, and at the same time the lower one is elevated by the foot lever. A depression of the latter then lowers the bottom die, and leaves the mass of clay, pressed into the desired form, in the hands of the workman. This is laid with others upon a rack to undergo the process of air drying. The entire space in the centre of the press room as well as a part of the second floor of the main building is occupied by these racks.

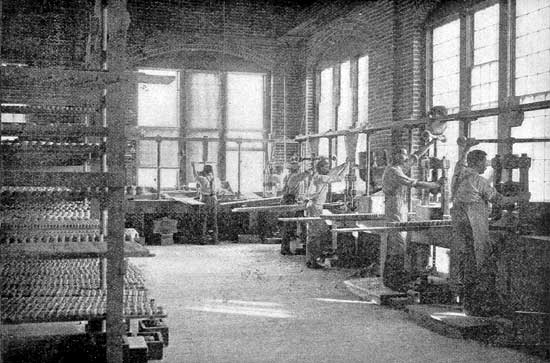

| |||

| Partial View of Press Room. |

The door in the press room opens into a spacious room which occupies part of the second floor at the left wing and the whole of the main building. In this room all the pieces are touched up; the burrs are removed from all the holes through which screws and punchings are to pass; the marks of the dies are cut off and the pieces put into final condition for baking and sent to the kilns.

Descending from the finishing room, the kiln room on the ground floor is reached, where are to be found four pottery kilns constructed after the latest approved methods. Around the kiln stands piles of yellow "hillers" and "saggers" which are made in one corner of the kiln room. These are filled with the pieces of clay, covered and hermetically sealed. The kiln is then filled and the doors closed.

After the first baking the porcelain comes out in the form of a hard, white, compact "biscuit". For certain insulating purposes, this "biscuit" is employed as it comes from the kilns. It is non-absorbent to a high degree, and is used for socket bases and other purposes where the porcelain is not exposed. For switch bases, insulators, cut-outs, etc., however, the porcelain is glazed, and subjected to another firing. When it leaves the firing kiln it is beautifully white, compact in texture, extremely hard, and has exceedingly high insulating properties.

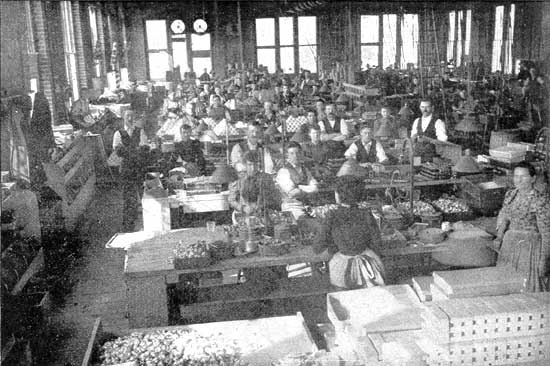

From the kilns the porcelain which is to be used in cut-outs, switches, sockets, transformer connecting boards, and in many other appliances, is taken to the second story of the right wing of the building, where the metal parts are attached.

The insulators for special work, such as for transmission at very high voltages, are tested in a small room adjoining. Each insulator is subjected to as severe a test as could be devised, and before being accepted as satisfactory must show its capability of withstanding a pressure of 25,000 volts alternating current. In order to test the endurance of these insulators, the testing current has raised as high as 52,000 volts before any of these special insulators gave away. The only trace of the enormous pressure then apparent on the outside of the insulator was a pin point hole scarcely perceptible.

| |||

| Partial View of Assembly Room. |